In the 1931 movie Frankenstein, the doctor’s hunchback assistant Franz raids the medical school’s lab to retrieve a brain for the monster. Whoops! He drops the jar that has the good brain and takes the bad brain instead – the brain of a demented murderer. (Video below.)

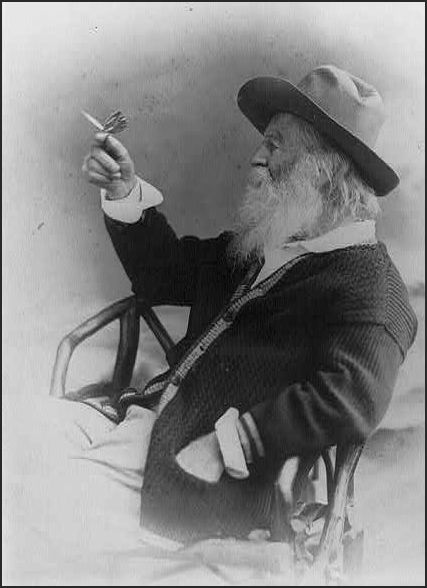

Who would have guessed that there is some factual basis for this set piece? Walt Whitman’s brain may have been on the back of someone’s mind as the scenario was written, though it cannot be proved for certain.

You see, Walt Whitman’s postmortem brain was put into some sort of a jam jar, and somebody dropped it, and it shattered. The brain, not the jar … or rather, probably, both. Or neither. Actually, it’s not certain the brain ever made it into a jar, or was dropped while it was in a sort of a rubber sack.

When I posted about “The Curious and Complicated History of Lenin’s Brain” two years ago, little did I know I would be writing a grisly sequel so soon. But scholar Brian Burrell has written an absolutely riveting account of Walt Whitman’s brain. I just discovered it (thanks to Twitter and Lapham’s Quarterly) in a back issue of the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, the preeminent journal on America’s bard, but one not usually given to sensational revelation. (The 27-page article, “The Strange Fate of Whitman’s Brain,” is downloadable here.)

According to our scholar Burrell:

“When Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein she made no mention of brains. To anyone who comes to the legend via the 1931 film instead of the 1818 novel, this might seem odd. But then the legend of Frankenstein has changed considerably since Shelley’s time in order to keep in step with the science that inspired it. If there are no brains in jars in Frankenstein the novel, it is because at the time she conceived the book, there were no brains in jars at all, and there would not be any for some time to come. The modern preoccupation with the human brain, it turns out, is a relatively recent phenomenon. Before Shelley’s time, very few people gave it much thought.”

Whitman wrote in 1855: “I have said that the soul is no more than the body. And I say that the body is not more than the soul.” But did he expect anyone should take this thought quite so much at face value?

Whitman wrote in 1855: “I have said that the soul is no more than the body. And I say that the body is not more than the soul.” But did he expect anyone should take this thought quite so much at face value?

Eight years after Lord Byron suggested that Mary Shelley write a horror story, the Romantic poet died, and his brain was removed at autopsy and weighed. That was the beginning. Others joined the party: Daniel Webster, Gaetano Donizetti, Ivan Turgenev, and many others had their brains removed, autopsied, and weighed, with a religious solicitude and ritual exactitude not shown since the days of the pharaohs. Great men, it was reasoned, would have magnificent and extraordinary brains. And by studying these brains, we could anatomize genius. A number of famous men felt they would be fit objects for such a study, and pledged their brains to science. Unfortunately, the weight of many of their brains fell short of expectations.

Could things get sillier? They could. And where else but France? In 1876, a French group formed the first brain donation society:

“They named it, rather eerily, the Société Mutuelle d’Autopsie (the Society of Mutual Autopsy). In their revolutionary fervor, they sealed their compact with a pledge that had the portentous ring of a fraternal oath: ‘Free thinker, loyal to scientific materialism and the radical Republic, I intend to die without the interference of any priest or church. I bequeath to the School of Anthropology my head, face, skull, and brain, and more if it is necessary. What remains of me will be incinerated.’”

Whitman showed an early interest in phrenology, a means to measure the internal qualities of a man by the bumps of his head. But he eventually outgrew this enthusiasm, citing Oliver Wendell Holmes’s remark that “you might as easily tell how much money is in a safe feeling the knob on the door as tell how much brain a man has by feeling bumps on his head.” However, in a moment of illness, the old faith returned. At least enough so that he, too, succumbed and signed away his brain. He owed it to science.

Whitman showed an early interest in phrenology, a means to measure the internal qualities of a man by the bumps of his head. But he eventually outgrew this enthusiasm, citing Oliver Wendell Holmes’s remark that “you might as easily tell how much money is in a safe feeling the knob on the door as tell how much brain a man has by feeling bumps on his head.” However, in a moment of illness, the old faith returned. At least enough so that he, too, succumbed and signed away his brain. He owed it to science.

The denouement was revealed years later by the renowned anatomist, Dr. Edward Spitzka in 1907. A throwaway comment in the doctor’s magnum opus admitted that the brain was “said to have been dropped” by “a careless attendant in the laboratory.” Investigations by Whitman’s friends revealed the dismaying facts: the brain “was destroyed either during the autopsy or while being conveyed to the jar, or in the jar before the hardening process by formaldehyde had been completed” … “the records state quite definitely that the brain was accidentally broken to bits during the pickling process.” Whitman’s devoted friend William Sloane Kennedy scribbled, “This is a grewsome story!”

Time has not been kind to this particular scientific endeavor, and it’s hard to believe anyone ever took it seriously. Burrell wrote: “The founders of the Brain Society had acted on the enthusiasm of a moment of history of science that turned out to be a passing phase. Had someone not dropped Whitman’s brain, they would hardly be remembered at all.”

Spitzka, later the editor of two editions of Gray’s Anatomy, never recovered from the professional fiasco. Still in his twenties, he took to the bottle, and not the pickling kind. He began to imagine that ex-convicts were stalking him, seeking revenge for his brain snatchings at the prisons in his salad days. He had a nervous breakdown. He died at 46, and donated his brain – but there were no true believers left to study it. Brains had accumulated faster than any interest in them. Even the smart ones.

Spitzka was one of the last eminent men to be painted by Thomas Eakins, who was in his last days and could barely hold a brush. It would remain unfinished,

“except for the depiction of a plaster brain cast which Spitzka cradles in his right hand. (It was painted in by Eakins’s wife.) As Eakins left the work, Spitzka stands in ghostly outline, unrecognizable, still waiting to be immortalized. In the 1930s, the canvas was cut down from a full length portrait to make it more marketable, and the image of the brain was discarded, leaving nothing more than the indistinct outlines of a presumably great man. The painting now resides, out of sight, in a storage room of Washington’s Hirshhorn Gallery.”

A reminder of how speedily tragedy descends into farce and back to tragedy again. It’s also a reminder of the tomfoolery of hubris – scientific or otherwise. How could anyone expect that the unique concoction of an individual’s energy, will, spirit, character, élan vital, whatever, might be so easily reducible to scale measurements and creases on the brain?

After all, today we all know the real answer to the mysteries of genius and destiny lies in our DNA. That’s what the important scientists tell us.

Postscript on 6/27: Big Think has some thoughts on Whitman’s link with Dracula – and discusses the Book Haven and this column, too. It’s over here.

Tags: Brian Burrell, Daniel Webster, Edward Spitzka, Gaetano Donizetti, Ivan Turgenev, Lord Byron, Mary Shelley, Thomas Eakins, Walt Whitman, William Sloane Kennedy

June 14th, 2012 at 9:44 am

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yH97lImrr0Q

June 14th, 2012 at 10:55 am

My Stanford computer won’t let me watch this – it’s protecting me from cyper-cooties. I’ll have to watch this when I get home, Max.

June 14th, 2012 at 8:07 pm

Watched it. Yup. That’s the general idea.

June 17th, 2012 at 8:06 pm

[…] Book Haven discovers what Frankenstein has to do with Walt Whitman’s brain, and, less whimsically, the man who volunteered for […]

July 6th, 2012 at 6:01 am

[…] Frankenstein and Walt Whitman’s brain: “This is a grewsome story” Cynthia Haven, The Book Haven, Stanford University, June 13, 2012 […]