“Yes – that was an actual moth,” Walt Whitman told his sidekick and chronicler, Horace Traubel; “the picture is substantially literal: we were good friends: I had quite the in-and-out of taming, or fraternizing with, some of the insects, animals.”

“Yes – that was an actual moth,” Walt Whitman told his sidekick and chronicler, Horace Traubel; “the picture is substantially literal: we were good friends: I had quite the in-and-out of taming, or fraternizing with, some of the insects, animals.”

This was his myth he told of himself. He confessed to historian William Roscoe Thayer, “I’ve always had the knack of attracting birds and butterflies and other wild critters.”

The 1883 photo from the Miami Herald was his favorite photo of himself – and, like Lincoln, he relentlessly documented himself in photos. But the man who anonymously (and very enthusiastically) reviewed his own books was not one to balk at a fact.

And fact was, he was a devoted opera-goer, a man who, until the end of his life, read ten newspapers a day. He was no hayseed, but a city slicker – a Long Island born journalist and government clerk. So why the St. Francis of Assisi shtick?

It remains one of America’s great literary mysteries. One thing is clear: the gift for self-reinvention is the great seal upon the American psyche. Think Whitman. Think Lincoln. Think Gatsby. Think Obama.

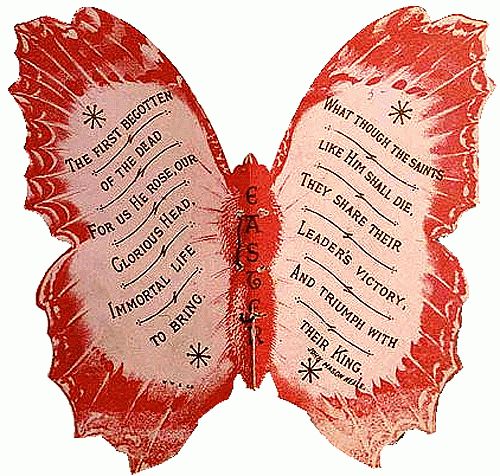

Here’s another fun fact: the alleged moth was “a gaudy cardboard butterfly produced in large quantities as part of an Easter celebration.” How do we know? In 1942, the Library of Congress shipped its most precious holdings inland. A crate with ten of Whitman’s notebooks went to Ohio. When the crate came back in 1944, the notebooks were gone. Fifty years later, in 1994, a young man showed up at Sotheby’s with four of the notebooks from his father’s estate. Thank you, sir, wherever you are: when he learned of their history, he returned them, without trying to get a penny of the estimated half-a-million dollars the cache was worth.

Here’s another fun fact: the alleged moth was “a gaudy cardboard butterfly produced in large quantities as part of an Easter celebration.” How do we know? In 1942, the Library of Congress shipped its most precious holdings inland. A crate with ten of Whitman’s notebooks went to Ohio. When the crate came back in 1944, the notebooks were gone. Fifty years later, in 1994, a young man showed up at Sotheby’s with four of the notebooks from his father’s estate. Thank you, sir, wherever you are: when he learned of their history, he returned them, without trying to get a penny of the estimated half-a-million dollars the cache was worth.

But here’s the big surprise: among the materials was the cardboard butterfly you see at right. The words are from John Mason Neale’s Easter hymn which began to appear in hymnbooks in the 1850s. Yup, it’s the insect from the photo.

John Lienhard of the University of Houston explains away Whitman’s gaffe this way:

So Whitman used the new cameras to make himself part of the poem. His own image became a dimension of his self-expression. He didn’t put his name on the title page of Leaves of Grass, he put his photo there – standing in rough clothes, the image of action, the image of the America he was writing about.

We all do that, of course. We offer a face to the world — strong, caring, reckless, intellectual, sinister. We all try to do what Whitman succeeded in doing. In the end, that fake butterfly doesn’t tarnish the poet at all; it explains him.

Whitman’s poetry was visual art. It was theater. Poetry was a process where he struggled to be one-and-the-same with the face he showed to the world. That’s surely the hardest thing any of us ever does. We try to decide whether we’re gentle or tough, while the real butterflies circle – always outside our reach.

Which is a fancy way of saying he lied, lied, lied. But this goes some way towards redeeming him, also describing the contents of the crate: “Here were draft portions of his epic poem, Leaves of Grass. Young Whitman described his work as a nurse in a Civil War hospital. That part gives us a very human picture of Whitman. He wrote letters for men who couldn’t write, and he recorded their deaths. He talked about requests from the wounded and dying – for an orange – even for a piece of horehound candy.”

But butterflies wafting to his finger? A PR stunt, at best. He would have given James Frey and Greg Mortenson a run for their money.

(Fun piece on the whole matter from a Leonard Cohen fan, at 1heckofaguy, over here.)

Tags: Horace Traubel, Walt Whitman

June 18th, 2012 at 2:26 pm

As a writer, I can say: writers don’t lie.

We make stuff up.

December 27th, 2012 at 12:56 pm

I wish the author had a better grasp of Whitman’s life and times.

“So why the St. Francis of Assisi shtick?

It remains one of America’s great literary mysteries.”

Whitman was a poet of nature and the body and as such was both glorified and reviled in his time. The question why the butterfly belies an almost willful ignorance of his purpose in crafting his work to fly in the face of 19th Century pretensions. If it was, indeed, PR, it was with a lifelong purpose that he succeeded in achieving, a forerunner of the movement toward reverencing all life.

And as to the “lie, lie, lie” — I agree with Shelly above and with James Broughton, one of the Whitman lineage, who wrote in the introduction to his memoir:

“Memory may forget a lot but it never forgets what should have occurred. All the events in this book are true, including those that did not happen.”

December 27th, 2012 at 1:32 pm

The “author” being me? Admittedly, it’s been a few years since I researched, wrote about, and spoke about Whitman. As I recall, his habit of (favorably) reviewing his own poems and otherwise promoting himself was controversial even in his own day. Of course, in that, as in much else, he was ahead of his times.

So your contention is that he did the fake butterfly as a sort of spoof of 19th century pretensions? I’m not clear about your point. (I’m also not sure how you can reverence all life with a dead butterfly.)

I love the Broughton quote. Was that before or after Ken Kesey’s famous, “But it’s the truth even if it didn’t happen”? In any case, both are true.

October 12th, 2016 at 2:42 pm

Thanks for the little piece on a favorite photo of mine. I was wondering if, in his time, he was signaling that he was gay. Probably not. In my time, authors, both male and female, have done author photos pointing a pistol out at the reader. These authors I don’t think we big into guns, but I could be wrong.

I like that Whitman used a butterfly in the photo to signal his playfulness, his love of nature (he took long walks and wrote plenty about nature), and perhaps a gentle kind of masculinity.

October 12th, 2016 at 2:48 pm

Nice thought, Chuck.