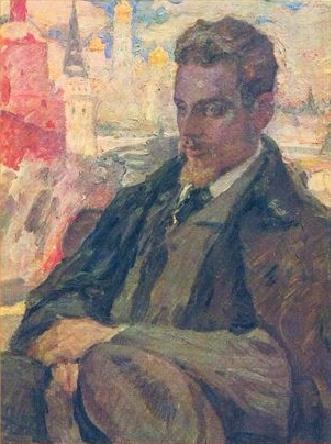

Last week at lunch with a friend, we both shared our distaste for the current thinking to defend the humanities – I’ve written about this in the last two days in a rant here and with Nobel laureate Coetzee’s remarks here. The best antidote I know is Joseph Brodsky‘s Nobel lecture, excerpted below. In fact, I focused on this essay during a lively get-together at the Menlo Circus Club recently, and it provoked a stimulating discussion.

Not everyone appreciates Brodsky’s circumlocutious Russian sentences, I know, but it’s well worth bearing out, believe me.

From the Nobel lecture (or read the whole thing here):

If art teaches anything (to the artist, in the first place), it is the privateness of the human condition. Being the most ancient as well as the most literal form of private enterprise, it fosters in a man, knowingly or unwittingly, a sense of his uniqueness, of individuality, of separateness – thus turning him from a social animal into an autonomous “I”. Lots of things can be shared: a bed, a piece of bread, convictions, a mistress, but not a poem by, say, Rainer Maria Rilke. A work of art, of literature especially, and a poem in particular, addresses a man tête-à-tête, entering with him into direct – free of any go-betweens – relations.

It is for this reason that art in general, literature especially, and poetry in particular, is not exactly favored by the champions of the common good, masters of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. For there, where art has stepped, where a poem has been read, they discover, in place of the anticipated consent and unanimity, indifference and polyphony; in place of the resolve to act, inattention and fastidiousness. In other words, into the little zeros with which the champions of the common good and the rulers of the masses tend to operate, art introduces a “period, period, comma, and a minus”, transforming each zero into a tiny human, albeit not always pretty, face.

The great Baratynsky, speaking of his Muse, characterized her as possessing an “uncommon visage”. It’s in acquiring this “uncommon visage” that the meaning of human existence seems to lie, since for this uncommonness we are, as it were, prepared genetically. Regardless of whether one is a writer or a reader, one’s task consists first of all in mastering a life that is one’s own, not imposed or prescribed from without, no matter how noble its appearance may be. For each of us is issued but one life, and we know full well how it all ends. It would be regrettable to squander this one chance on someone else’s appearance, someone else’s experience, on a tautology – regrettable all the more because the heralds of historical necessity, at whose urging a man may be prepared to agree to this tautology, will not go to the grave with him or give him so much as a thank-you.

Language and, presumably, literature are things that are more ancient and inevitable, more durable than any form of social organization. The revulsion, irony, or indifference often expressed by literature towards the state is essentially a reaction of the permanent – better yet, the infinite – against the temporary, against the finite. To say the least, as long as the state permits itself to interfere with the affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere with the affairs of the state. A political system, a form of social organization, as any system in general, is by definition a form of the past tense that aspires to impose itself upon the present (and often on the future as well); and a man whose profession is language is the last one who can afford to forget this. The real danger for a writer is not so much the possibility (and often the certainty) of persecution on the part of the state, as it is the possibility of finding oneself mesmerized by the state’s features, which, whether monstrous or undergoing changes for the better, are always temporary.

The philosophy of the state, its ethics – not to mention its aesthetics – are always “yesterday”. Language and literature are always “today”, and often – particularly in the case where a political system is orthodox – they may even constitute “tomorrow”. One of literature’s merits is precisely that it helps a person to make the time of his existence more specific, to distinguish himself from the crowd of his predecessors as well as his like numbers, to avoid tautology – that is, the fate otherwise known by the honorific term, “victim of history”. What makes art in general, and literature in particular, remarkable, what distinguishes them from life, is precisely that they abhor repetition. In everyday life you can tell the same joke thrice and, thrice getting a laugh, become the life of the party. In art, though, this sort of conduct is called “cliché”.

Art is a recoilless weapon, and its development is determined not by the individuality of the artist, but by the dynamics and the logic of the material itself, by the previous fate of the means that each time demand (or suggest) a qualitatively new aesthetic solution. Possessing its own genealogy, dynamics, logic, and future, art is not synonymous with, but at best parallel to history; and the manner by which it exists is by continually creating a new aesthetic reality. That is why it is often found “ahead of progress”, ahead of history, whose main instrument is – should we not, once more, improve upon Marx – precisely the cliché.

Nowadays, there exists a rather widely held view, postulating that in his work a writer, in particular a poet, should make use of the language of the street, the language of the crowd. For all its democratic appearance, and its palpable advantages for a writer, this assertion is quite absurd and represents an attempt to subordinate art, in this case, literature, to history. It is only if we have resolved that it is time for homo sapiens to come to a halt in his development that literature should speak the language of the people. Otherwise, it is the people who should speak the language of literature.

On the whole, every new aesthetic reality makes man’s ethical reality more precise. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics; The categories of “good” and “bad” are, first and foremost, aesthetic ones, at least etymologically preceding the categories of “good” and “evil”. If in ethics not “all is permitted”, it is precisely because not “all is permitted” in aesthetics, because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. The tender babe who cries and rejects the stranger or who, on the contrary, reaches out to him, does so instinctively, making an aesthetic choice, not a moral one.

Aesthetic choice is a highly individual matter, and aesthetic experience is always a private one. Every new aesthetic reality makes one’s experience even more private; and this kind of privacy, assuming at times the guise of literary (or some other) taste, can in itself turn out to be, if not as guarantee, then a form of defense against enslavement. For a man with taste, particularly literary taste, is less susceptible to the refrains and the rhythmical incantations peculiar to any version of political demagogy. The point is not so much that virtue does not constitute a guarantee for producing a masterpiece, as that evil, especially political evil, is always a bad stylist. The more substantial an individual’s aesthetic experience is, the sounder his taste, the sharper his moral focus, the freer – though not necessarily the happier – he is.

It is precisely in this applied, rather than Platonic, sense that we should understand Dostoevsky‘s remark that beauty will save the world, or Matthew Arnold‘s belief that we shall be saved by poetry. It is probably too late for the world, but for the individual man there always remains a chance. An aesthetic instinct develops in man rather rapidly, for, even without fully realizing who he is and what he actually requires, a person instinctively knows what he doesn’t like and what doesn’t suit him. In an anthropological respect, let me reiterate, a human being is an aesthetic creature before he is an ethical one. Therefore, it is not that art, particularly literature, is a by-product of our species’ development, but just the reverse. If what distinguishes us from other members of the animal kingdom is speech, then literature – and poetry in particular, being the highest form of locution – is, to put it bluntly, the goal of our species.

I am far from suggesting the idea of compulsory training in verse composition; nevertheless, the subdivision of society into intelligentsia and “all the rest” seems to me unacceptable. In moral terms, this situation is comparable to the subdivision of society into the poor and the rich; but if it is still possible to find some purely physical or material grounds for the existence of social inequality, for intellectual inequality these are inconceivable. Equality in this respect, unlike in anything else, has been guaranteed to us by nature. I am speaking not of education, but of the education in speech, the slightest imprecision in which may trigger the intrusion of false choice into one’s life. The existence of literature prefigures existence on literature’s plane of regard – and not only in the moral sense, but lexically as well. If a piece of music still allows a person the possibility of choosing between the passive role of listener and the active one of performer, a work of literature – of the art which is, to use Montale‘s phrase, hopelessly semantic – dooms him to the role of performer only.

In this role, it would seem to me, a person should appear more often than in any other. Moreover, it seems to me that, as a result of the population explosion and the attendant, ever-increasing atomization of society (i.e., the ever-increasing isolation of the individual), this role becomes more and more inevitable for a person. I don’t suppose that I know more about life than anyone of my age, but it seems to me that, in the capacity of an interlocutor, a book is more reliable than a friend or a beloved. A novel or a poem is not a monologue, but the conversation of a writer with a reader, a conversation, I repeat, that is very private, excluding all others – if you will, mutually misanthropic. And in the moment of this conversation a writer is equal to a reader, as well as the other way around, regardless of whether the writer is a great one or not. This equality is the equality of consciousness. It remains with a person for the rest of his life in the form of memory, foggy or distinct; and, sooner or later, appropriately or not, it conditions a person’s conduct. It’s precisely this that I have in mind in speaking of the role of the performer, all the more natural for one because a novel or a poem is the product of mutual loneliness – of a writer or a reader.

Read the whole thing here.

November 28th, 2013 at 6:03 pm

[…] The Book Haven highlights Joseph Brodsky’s Nobel lecture. […]

December 3rd, 2013 at 4:02 am

[…] poems, Letters to Ted, written after Hughes’s death, as well as a memoir of Nobel prizewinner Joseph Brodsky. (Read the […]