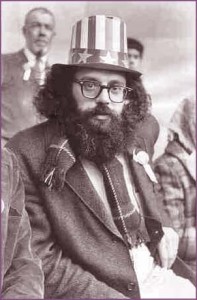

Onstage in 2013 at Stanford

Beat poet Diane di Prima died today after long illness at 86. She was born in Brooklyn, a second-generation American of Italian descent. She went to Swarthmore, then Greenwich Village, and joined Timothy O’Leary’s community in upstate New York, made a lifetime move to San Francisco. She published more than 40 books, including This Kind of Bird Flies Backwards, Revolutionary Poems, and the semi-autobiographical Memoirs of a Beatnik. Seven years ago, she came to Stanford to read her poems and have one of the legendary “How I Write” onstage conversations with Hilton Obenzinger. Below, she and Hilton relax before the November 6, 2013, event. You can listen to the recording of the conversation over at iTunes “How I Write” (it’s #53) here.

His recollections of the conversation below, excerpted from How We Write: The Varieties of Writing Experience (by Hilton Obenzinger, published by the “How I Write” Project at Stanford):

It’s hard to imagine a more independent writer than poet Diane di Prima. She emerged as part of the beatnik scene at a very early age in the 1950s, although the beatniks never called themselves that until somebody else came up with the term. Once she decided that she was going to be a poet at the age of fourteen, “it wasn’t really a happy moment, because I knew immediately what wasn’t going to happen.” As she put it, she was forgoing “matched dishes, a washing machine, a regular consensus lifestyle of any sort” in exchange for the freedom to create any way she chose.

She had been caught writing when she was in summer school, and the teacher made her read a poem out loud: “It was all downhill from then,” she joked. Once di Prima decided to be a poet, she also made sure to write every day. She had a lined composition book that had the slogan “No Day Without a Line” in Latin on the front, and she maintained that practice throughout her life. She went to Hunter College High School in Manhattan, where she read the romantics, but her school was so intellectual that “reading and loving the romantics was a no-no. You would rather be caught reading a comic book than Thomas Wolfe’s novels. I would lie and say, ‘Well, oh no, I’m reading Archie.’” But she met with a like-minded group of girls before class, including the future poet Audre Lorde, and they would read their poems to each other. That was her “first “workshop.”

She visited him in the hospital.

She dropped out of college after her first year, and was largely self-taught, initially through a combination of three influences: “I studied with Keats and Pound,” she said. “Keats’s letters told me everything I needed to know until I found [Ezra Pound’s] ABC of Reading.” She needed to learn a bit more, such as mastering “the building blocks of poetry—the image, the dance of the language, and the music of words.” Those three elements— Keats, Pound, and the building blocks—constituted her initial education, along with her sessions with Ezra Pound himself.

At that time, Pound was confined as a patient at St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital in Washington, D.C. rather than face a trial as a traitor for making radio broadcasts in support of Mussolini during the war. Despite being very shy, di Prima decided to go visit the poet: “I’m not going to lose the opportunity to look this man in the eye and talk to him.” She had sent him some poems in advance, and he wrote back: “They seem to me to be well written. But—no one ever much use as critic of younger generation.” She took this as encouragement, but this was an important lesson that gave her direction for how to teach later in life: “Keep my hands off younger people’s work. Try to grasp what they’re after, and if I can get that out by hanging out with them, then I could nudge them in that direction.”

She could suggest books to read, but she kept to that idea: Not much use as critic of the younger generation. Di Prima went to St. Elizabeth’s with a friend and stayed at the house of Pound’s lover, Sheri Martinelli, visiting with the poet every day for four or five days. The hospital staff knew she couldn’t be there for long, so they let her in frequently.

After she dropped out of college she spent half the day writing and half studying. “I took the agenda, more or less, that Pound proposed, and taught myself some Homeric Greek so I could sound out the poems.” She also studied classical Greek grammar and Latin. “I’d study usually at home, and then I’d take my notebook and go out and write, run around the city and write. And then the typing and revising happened at home in the evening. We needed very little, so $70 a month covered the rent. The house was $33, the apartment—four of us lived in it. It was a cold-water flat. No heat. Bathroom in the hall.” Her bohemian lifestyle flowed from her commitment to her art—not the other way around.

Thinking or composing “as it happens” is something that poet Diane di Prima tried early in her career. Jack Kerouac stayed at her place in New York on the way to India in February 1957. With Ginsberg, Kerouac, and others in her small apartment, everyone started to read their poems out loud.

They read their poems together.

After she read one of hers, Kerouac asked, “What did it look like when you first wrote it?” She looked at her early draft, and to her surprise she liked it. What she got from that experience was the knowledge that “you could always go back to those drafts and pull something out when you got stuck, you know; and then I got the sense of how your mind worked in the first place, and that was very interesting.” She had taken a class on dance composition with a choreographer, who implanted the idea that everything has a form—everything. “He said nothing else. After about ten minutes we all started to go out the door,” di Prima said. “We were looking at everything. Oh, that has a form; that has a form. He was telling us that all forms are okay. Leave your mind alone. Don’t mess with everything all the time.” As a consequence, she began following her mind in her writing wherever it went: “Write exactly what’s happening as closely as you can.”

She wanted to write something longer, and she took what she learned from that dance class, “taking a structure and then hanging absolute freedom on the structure.” She took the eight trigrams (three-line symbols) that make up the I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes, and she would immerse herself in the qualities of each trigram: “I listened to that kind of music. I’d just be in that kind of state for a couple of months. And then I’d start writing. And I’d just write. And I’d write whatever showed up on the wall in front of my big IBM typewriter.” In this way, in a kind of mystical state, she wrote The Calculus of Variation.

Di Prima was wondering how to revise the book, “how to make it smooth and really hip or kind of avant-garde prose. And I knew that if I did that I would be violating this book, so all of a sudden I decided, ‘Hmm, I can’t touch this. I’m going to leave all the flaws in it.’” She got an offer from New Directions to publish it, but they wanted to assign her an editor, and she declined, explaining, “This is in the nature of a received text. I can’t touch it. And I never did. And so I published it myself. And never did publish with New Directions.” For a poet to get published by New Directions was (and still is) a major accomplishment, but given her “calling,” her artistic purpose outweighed whatever she would gain for her “career.”

After The Calculus of Variation, Diane di Prima returned to revision in her other works, although much of her poetic method would be to transcribe what she would see before her as a “received text.”

At Stanford in 2013. (Photo: Les Gottesman)

Tags: Diane di Prima, Hilton Obenzinger

October 26th, 2020 at 7:33 am

So very saddened. I published a short work of hers on H.D. and audited over a 100 of her hidden religions tapes – she was a wonder! A deep tear in the fabric of our being to see her go. A stone for her by pond in middle of a forest here on the Eastern shore of Maryland.

October 26th, 2020 at 9:11 am

❤️

October 26th, 2020 at 12:59 pm

It’s sad to hear this news, having been touched by Diane’s warmth and her sense of humor, not to mention her superb poetry. She was a wonderful teacher who ecouraged students to trust in themselves, to listen to their surest voice. There is freedom in that, and gratitude for her generosity of spirit.

October 27th, 2020 at 7:37 am

❤️

October 28th, 2020 at 3:13 pm

Cynthia, wonderful entry.

If you don’t mind my saying so, I loved your Girard biography. Tremendously & in tears.

As soon as my online teaching responsibilities abate, right to your new book on the great man!

October 28th, 2020 at 3:18 pm

Thank you, Neil!

October 30th, 2020 at 1:32 am

One of my first female poet influences. Never got to meet her.