Were the 1950s really that bad?

Friday, November 21st, 2014 The 1950s have taken a bum rap for years. You remember the 1950s: women were locked in their houses and forced to bake apple crumble and change diapers while men took their hats and briefcases to the office. Everyone was repressed, and unable to express their Innermost Selves. No one had any fun at all.

The 1950s have taken a bum rap for years. You remember the 1950s: women were locked in their houses and forced to bake apple crumble and change diapers while men took their hats and briefcases to the office. Everyone was repressed, and unable to express their Innermost Selves. No one had any fun at all.

People forget how close the West came to losing it all. Had Hitler avoided a few military blunders, we might all be speaking German right now. Believe it or not, many men and women were happy to beat their swords into ploughshares and devote themselves to the virtues of peace. Being a riveter, though doubtless empowering, was not that much of a career enhancer. For kids, especially, it wasn’t a half-bad era. You had a pretty good chance of growing up in an intact home with the same parents, and children could walk to school safely and attend classes without gunfire. W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, Elizabeth Bishop, and Robert Frost were still alive and writing poems, and the Partisan Review was in its prime. Was it that much worse than the 1930s, the 1910s?

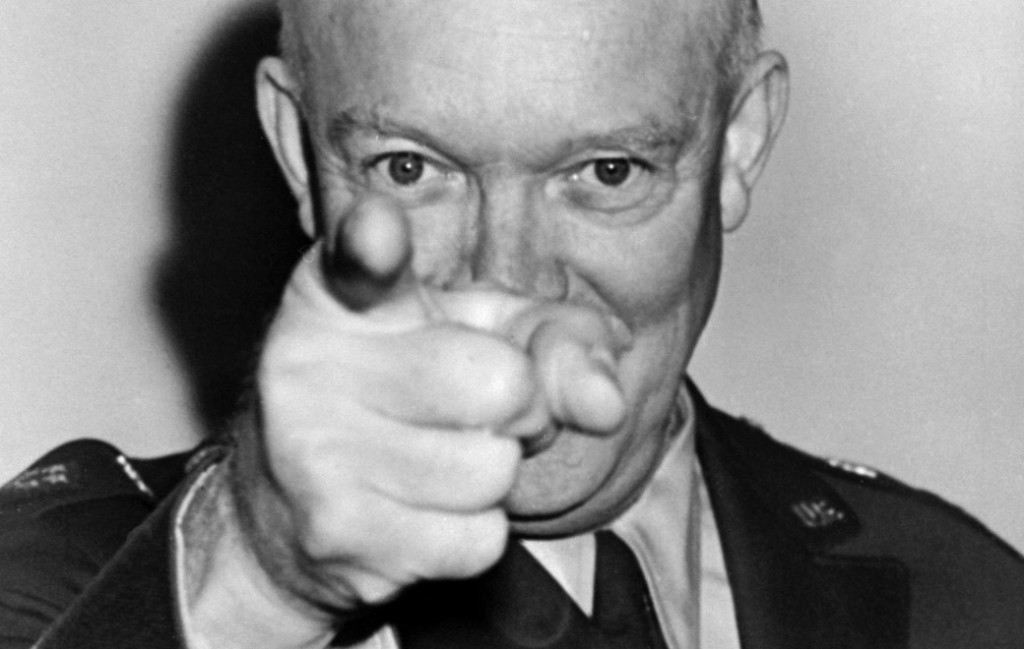

Two recent reviews over at Books Inq seem to reinforce my sense that the era has been much maligned. The book at hand is Paul Johnson‘s Eisenhower: A Life – a biography that’s 134 pages long, including the index. The Times Literary Supplement review said of Johnson: “His zesty, irreverent narratives teach more history to more people than all the post-modernist theorists, highbrow critics, and dons put together.”

My colleague Frank Wilson reviewed the book here, in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

“As recounted in Eisenhower: A Life, a new brief biography by the British writer Paul Johnson, the life of Dwight David Eisenhower was one of steady, uninterrupted success – five-star general, supreme commander of Allied Forces in Europe during World War II, 34th president of the United States, elected twice, both times by landslides, and still popular when he left office. Heck, just a year before he died, he hit a hole-in-one on the golf course.

“Yet one feels sad when one finishes Johnson’s book. Not for Eisenhower, but for the country he served so well.

“A joke making the rounds as his presidency neared its end told of the Eisenhower doll: You wound it up and it did nothing for eight years. But we could use plenty of that nothing these days. As Johnson points out, Eisenhower gave America nearly ‘a decade of unexampled prosperity and calm. The country had emerged from the Korean War and the excesses of McCarthyism. Inflation was low. Budgets were in balance or with manageable deficits. The military-industrial complex was kept under control. . . . Thanks to Ike’s fiscal restraint, prices remained stable and unemployment only a little more than 4 percent. …’

“Had he heard the joke about the doll, Eisenhower probably would have laughed, at least to himself. ‘He seems to have found it convenient and useful,’ Johnson writes, ‘for people to get him wrong. He chuckled within himself.’

“So, at the time, the all-too-conventional wisdom had it that he was inarticulate, not too bright, lacking in cunning, and lazy, preferring to hit the links and leave the business of government to subordinates. His critics, Johnson writes, got things exactly wrong: ‘Ike was highly intelligent, knew exactly how to use the English language, was extremely hardworking, and very crafty. In practice, he made all the key decisions, and everyone had to report to him on what they were doing and why.’ Like any genuine leader, Eisenhower did not insinuate. He issued commands. He led from above. … One in particular might find it interesting to learn that during six of Eisenhower’s eight years in office, both houses of Congress were controlled by the opposition party.”

Another one here by reviewer John Derbyshire, who seems to have suffered a sort of crush on the biographer once:

“In his 1983 book Modern Times, Paul Johnson made a point of talking up U.S. presidents then regarded by orthodox historians as second-rate or worse: Harding, Coolidge, Eisenhower. He wrote:

Eisenhower was the most successful of America’s twentieth-century presidents, and the decade when he ruled (1953-61) the most prosperous in American, and indeed world, history.

“The goal of political leadership is to secure for one’s country, so far as circumstances will allow, the things that most ordinary citizens wish for: prosperity and peace.

“On that score, Ike did superbly well. America’s 1950s prosperity glows golden in the memory of us who witnessed it, if only from afar. Peace? Paul Johnson draws a withering comparison between Ike’s masterly 1958 deployment to Lebanon—’the only American military operation abroad that Ike initiated in the whole of his eight years at the White House’—and the Bay of Pigs misadventure of the vain, shallow John F. Kennedy in the following administration.

“Discounting as best I can my partiality to P.J.’s prose, I’m convinced: This was our best modern President.”

Postscript on 11/24: Another country heard from! Not everyone agrees with the resurrection of Ike – below, Nevada blogger Bruce Cole elaborates on the comments he made Saturday. (Coincidentally, a Bruce Cole is a member of the Eisenhower Memorial Commission – this is not the same guy.) Colleague Bruce, who blogs over at A Citizen Paying Attention, disagrees with the reviews about Ike – but he concurs about the silliness of lumping cultural trends into decades – and don’t get me going on how much of the 1960s happened in the 1970s. Here’s the important part: he tells me he shares my enthusiasm for Czesław Miłosz.

Cynthia has been kind enough to ask me to elaborate a little on my hasty early Saturday morning comments about Eisenhower and the 1950s (two subjects, though they overlap).

First, I mentioned John Lukacs‘ review of several books about Ike. The review ran in Harper’s in 2002 and was collected in the anthology of his writings, which I cited. He makes several points about the (again, two) subjects of Cynthia’s original post. Many of the characteristics of the 1960s (or things we associate so easily with that decade, or things we bemoan as happening since the Good Old Days) began in the 50s: the decline in our manufacturing and our savings, the deterioration of our cities, the net outflow of gold from the United States, the increasing problems of our public education system, the demotion of jazz as our most popular music, the “sexual revolution,” etc. The point is not that these were the fruits of Eisenhower’s presidency. Rather, they remind us not to indulge in a false nostalgia about an arbitrary set of years (a nostalgia whose mirror image is, of course, the 50s as staid, awful, and repressive).

Now, about Ike. Eisenhower (who, as a general in 1945, telegraphed Marshall Zhukov assuring him that the Americans wouldn’t reach Berlin before the Russians) came into office with talk about rolling back Communism, as opposed to the “cowardly containment” (Nixon’s words) of Truman. I am hard put to see where this ever happened. We did watch as Hungary (having been covertly encouraged by us) got tromped on in 1956. Lukacs has written often, and persuasively, about the chances in the years just prior to this when the West could have taken advantage of relative Soviet weakness to negotiate some kind of genuine rolling back of Soviet dominance in Eastern Europe (Churchill, no softy, kept urging this course on Eisenhower). Even then, they removed themselves from Austria, forsook a naval base in Finland, recognized West Germany, etc.

All of that is as may be. Ike did not keep the “military-industrial complex under control.” The defense budget tripled throughout the fifties. Our military presence expanded all over the globe, including places where there was little or no Soviet threat. He fortunately did not intervene in Indo-China in 1954, but then there was little chance the US would. The Lebanon incursion in 1958 was an absurdity. The Korean truce of 1953 established what had been the status quo for about two years (nothing wrong with that, but it was no great accomplishment). Finally, there is that Bay of Pigs thing – all pre-packaged by Ike and the CIA for his successor, complete with “intelligence” assurances that a popular uprising against Castro would take place. So, “vain, shallow” JFK followed suit. Hmm, is there any reason to believe Richard Nixon would have fared better? No.

Then there is McCarthy. Ike did not work McCarthy’s destruction, but kept silent while various Senators in both parties prepared censure in the Senate. It also should never be forgotten how Ike kept silent while McCarthy repeatedly slandered Ike’s patron, General Marshall.

Much of the above I owe to Lukacs’ analysis (which I again urge everyone to read) with a few embellishments of my own and no apologies from me at that score! Let me add something, though, on our two, inter-related subjects.

The origins of Eisenhower’s rehabilitation go back, in no small measure, to an article Murray Kempton wrote in the 1960s (!) for Esquire with a title something like “The Underestimation of Dwight D. Eisenhower.” (Kempton was a great journalist, but when he went off the beam, look out!) The arguments were repeated by Garry Wills a few years later in an otherwise perceptive book, Nixon Agonistes. I think this was, in part, the reaction to “Camelot,” which spawned, of course, a multitude of anti-Camelots. We have a difficult time taking our presidents plain, anyway, and the contrast of the two in terms of age and “glamour” with LBJ following them, and Vietnam thrown into the mix, made it well-nigh impossible.

That leads me to the other subject (which actually I am more interested in). I, too, despise, “decade-talk.” Of course, the 50s were not simply the Age of Conformity and Repression. But notice how the nostalgia some people express for that time merely turns that idea inside out. I think this is the nub of the matter. So many of our debates occur between people who agree on terms and wouldn’t know a tertium quid if it hit them full in the face. That is why our “culture wars” have such staying power. Beyond the real issues, it is easy to sign up for a Line, a set of attitudes, a collection of loves and hates. Which, finally, is why the “bad” 50s will never go away as a cliché – but it is hardly alone in that.