Four poets, two versions of Orpheus

Wednesday, October 11th, 2017

Greville, for purposes of comparison.

“Thom Gunn once wrote a letter of reference for Edgar Bowers, and he evidently said afterward that the experience made him feel like Philip Sidney recommending Fulke Greville.” So Los Angeles poet Timothy Steele opens his “Two Versions of Orpheus” in the summer issue of the Yale Review. One thing the Gunn and Bowers shared: a deep grounding and love for the Renaissance poets, including of course Sidney and Greville.

We’ve written before about Gunn here and here, and about Bowers here and here, and even a little about Fulke Greville here, and Tim Steele here and here and here, among other places.

But that’s all in pieces. Tim’s essays are always thoughtful, erudite, and insightful, and this long piece is one of the best of them – and it begins with Gunn’s anecdote, which frames the essay.

You can read it for yourself, but if you don’t know either of the poets, who studied with Stanford’s Yvor Winters, here’s your introduction, which gives you a taste for the whole:

Gunn: a panther tattoo and an earring.

Even in the personal impressions they produced, Gunn and Bowers differed in ways that Sidney and Greville did. Just as Sidney was the cynosure of his era, Gunn was a rock star in the poetry world of the second half of the twentieth century. Tall and handsome, he combined courtly good manners – he was in person very thoughtful and considerate of others – with an appealingly piratical air. He wore an earring long before it was a common fashion accessory for men. On his right arm, he had a tattoo of a panther that he got in 1962 from Lyle Tuttle, the San Francisco artist who later did Janis Joplin’s tattoos and who tattooed the Allman Brothers with the mushroom design that has remained the band’s logo to this day. If Paolo Veronese painted Sidney, artists like Don Bachardy and Robert Mapplethorpe drew or photographed Gunn. The dust jackets of some of his books carry their portraits of him. Seeing these, many of us feel that, yes, this is the way a poet should look.

Counterpoint: Sidney as fashionplate.

Bowers was just the opposite. Reluctant to call attention to himself, he dressed in a quietly tasteful Brooks Brothers manner, and with his understated charm could have passed for the kind of cultivated civil servant that Greville became for Elizabeth and James I. Though a wonderfully intelligent and lively conversationalist, he had no artistic airs. As devoted as he was to poetry, he sometimes said, as Dick Davis recalled in a memorial essay on Bowers in Poets & Writers (2000), that one is a poet only when one is writing a poem. Further, he thought that the poet’s main responsibility was to write well and to produce the best individual poems he or she could, and he believed that it was ruinous to poets to imagine that they were more special than other people or had creative spirits that automatically conferred value on whatever they wrote. He worried that his contemporaries judged poets more by their appearance than by their work, and on one occasion during a literary dinner in Florence, his suspicion received ironic confirmation. One of the other guests, not realizing that Bowers had good Italian, remarked within his hearing that he obviously was not a real poet, in view of how well groomed he was. Such thoughtlessness irritated Bowers, but he recognized that it reflected the zeitgeist and resigned himself to the situation as best he could.

Bowers was a Brooks Brothers guy.

While on the subject of the folly of judging merely on appearances, I should add that Gunn, despite his outlaw image and his genuinely wild side, conducted his writing life with extraordinary meticulousness. Those who visited him at his house on Cole Street in San Francisco have noted how neatly he kept his room and library. As is shown by his notebooks and diaries archived at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, he was also an inveterate maker of to-do lists and was continually mapping out writing projects, quite a few of which he relinquished simply because there was not time enough in one life to do them all. Moreover, he maintained careful and extensive records of his publications and public appearances. In an essay in The Threepenny Review (2005), Wendy Lesser conveys the powerful impression produced by the thoroughness of this documentation.

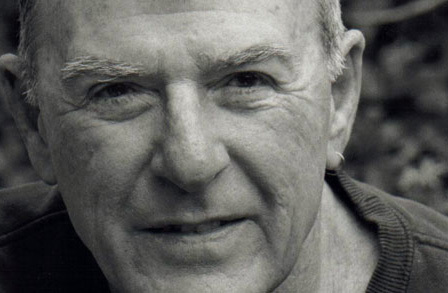

TIm

After Gunn’s death the previous year, and at the request of his longtime partner Mike Kitay, she and August Kleinzahler inspected Gunn’s study: ‘‘We found drawers of file folders containing every draft of every poem he had ever published, all sorted into book-manuscript order and each clipped to the finished, printed version of the poem; and we found schedules of every reading he had given for the past four decades, each with the list of poems to be read that night.’’

In contrast, Bowers possessed, in spite of his conventionally tasteful wardrobe and exquisitely poised intellect, the kinds of quirks and crochets we tend to associate with the artistic temperament. As he confessed in a 1999 radio interview with Troy Teegarden’s Society of Underground Poets, he was ‘‘very disorderly.’’

Read the whole thing here.