Can metaphysical ugliness promote beauty?

Monday, January 1st, 2024

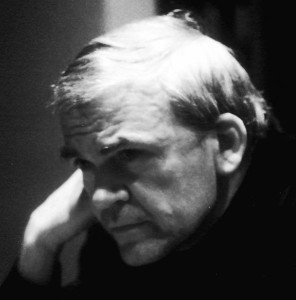

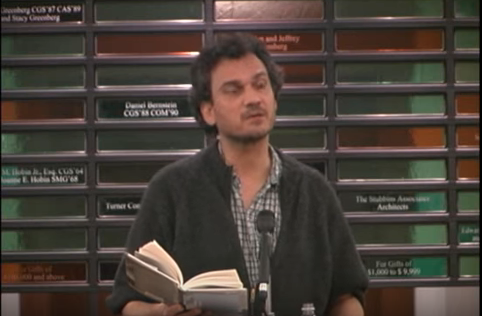

How do authors get away with shallow, shabby, venal, morally deficient characters who appall us … but nevertheless, we read on? Trevor Cribben Merrill, author of Minor Indignities, explains: “the ‘spirit of the author’ shields the reader from the characters, ‘drawing the poison’ from their negative qualities of arrogant stupidity, shallowness, and triviality.” He writes about it on Genealogies of Modernity, a project supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities to explain “how we became modern.”

Trevor writes: “This essay is about as close as I have come to articulating an artistic credo.” Excerpt from “Three Lessons in Beauty” below:

We would not want to spend time with Proust’s snobs. In their most honest moments, even his characters describe the fancy dinner parties they attend as boring and stifling. But to read about these soirées, and the people at them, is another matter. Similarly, if we were to encounter him in real life, Jane Austen’s Mr. Collins would be a bore; on the page, he is at once a bore, and, with his absurd boasts about the size of the chimney-piece at Rosings Park, a pure delight. In both cases the authors make us enjoy the sort of people we would try to flee at a cocktail party. It is not only that Proust’s prose and metaphors are exquisite, but that he turns the wretched maneuverings and deceit of his snobs into poetry. Out of pretense, dullness, and even malice, Austen, too, makes art.

“The formal innovations of the great masters always have a certain discreetness about them,” he writes. [italics his]

Recently while sick in bed I listened to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata 31, Op. 110 performed first by Rudolf Serkin and then by Glenn Gould. Composed in 1821, Op. 110 is the next to last of the composer’s piano sonatas, and falls squarely in his “late” period, during which he created many of his most beautiful and formally adventurous works. Beethoven is known for bridging classical and romantic styles. In his late years, however, he was also drawn to the contrapuntal music of the earlier baroque period.

The Op. 110 sonata is especially notable for its third movement, which employs musical structures from different moments in the history of music: classical homophony (a melody played by the right hand unfolding over chords played gently by the left); a more impassioned, stormy section expressing romantic emotion; and a fugue divided into two parts. In Serkin’s interpretation, and even more so in Gould’s, this fugue, built on a short, ascending theme, sounds very much like Bach. By paying reverent homage to the polyphony of Bach and Handel, Beethoven, as if by accident, created a novelty in the homophonic form par excellence, the sonata.

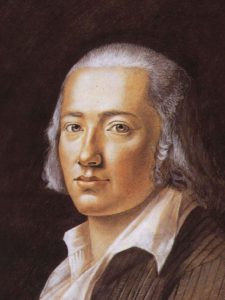

In one of his essays Milan Kundera praises this third movement of the Op. 110 sonata for “its extraordinary heterogeneity of emotion and form.” And yet, he adds, “the listener does not realize this, because the complexity seems so natural and simple.” From this beguiling naturalness Kundera draws the following lesson: “the formal innovations of the great masters always have a certain discreetness about them; such is true perfection; only among the small masters [petits maîtres] does novelty seek to call attention to itself.”

This observation calls to mind Virginia Woolf’s comment about Jane Austen: “of all the great writers,” she is “the most difficult to catch in the act.” One of Austen’s formal innovations occurs in Northanger Abbey, where she makes her “defense of the novel” as an art that gives “unaffected pleasure” while truthfully representing human nature in beautiful language. Austen admired Henry Fielding, who included mini-essays on the novel at the beginning of each of the eighteen books of Tom Jones.

When she shares her own thoughts on fiction half a century after Fielding, however, she makes them emerge seamlessly from her characters’ obsession with Gothic fiction, and—with the discretion of a great master—tucks them in at the end of chapter five. What in Fielding comes across as theoretical reflection added on to the fictional narrative is in Austen woven into the work’s fabric. In this way she keeps one foot in the aesthetic of the eighteenth-century novel, with its obtrusively playful authorial interventions, while bringing a new level of unity and polish to her chosen form.

To what other artists or works of art might Kundera’s insight apply? Because the kinds of formal innovations he singles out avoid drawing attention to themselves, it takes a certain amount of knowledge about a given art form to come up with good examples. And conversely, attempting to catch a glimpse of such shy novelties promotes a deeper appreciation for the habits of great artists as well as for the inner workings of artistic tradition.

Read the whole thing here.

Why? Because the reception of literary texts has shown that the luggage of identification bogs down a literary text. Because it has further been shown that labels actually alter the substance of a literary text and its meaning.

Why? Because the reception of literary texts has shown that the luggage of identification bogs down a literary text. Because it has further been shown that labels actually alter the substance of a literary text and its meaning.