I’m settling in for a long weekend with the proof pages and indexing for An Invisible Rope. A large pile of books have accumulated next to my bed, waiting to be read as I finish up a three-year endeavor. I expect most of them will be waiting there for some time.

I’m settling in for a long weekend with the proof pages and indexing for An Invisible Rope. A large pile of books have accumulated next to my bed, waiting to be read as I finish up a three-year endeavor. I expect most of them will be waiting there for some time.

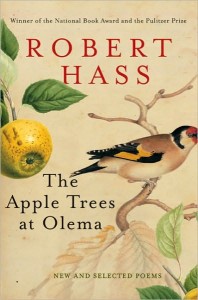

One of them is Robert Hass‘s The Apple Trees at Olema. It’s hard to sink into a volume of poems and enter someone else’s internal world when you are already being pulled into several directions, so I had postponed even cracking the spine. Hass’s poems are a bit like talking to him – digressions and self-interruptions, even in mid-sentence, predominate in conversations. An interview that enthralled at the time can require serious rethreading once you get an actual transcript. I wrote about his Pulitzer-winning Time and Materials (and predicted it would sweep the Pulitzer and National Book Awards at the time) for San Francisco Magazine — it’s here.

One thing Bob and I have in common is our longstanding enthusiasm for Czesław Miłosz. Among the finest things that Bob ever said to me was when he was relating how he came to be the chief translator for the elderly Polish poet, a collaboration which continued for decades: “So by accident, in the course of this, at an age when I was really too old to have a master anymore, I got to apprentice myself to this amazing body of poetry.” That kind of humility is rare in a world of large egos.

One thing Bob and I have in common is our longstanding enthusiasm for Czesław Miłosz. Among the finest things that Bob ever said to me was when he was relating how he came to be the chief translator for the elderly Polish poet, a collaboration which continued for decades: “So by accident, in the course of this, at an age when I was really too old to have a master anymore, I got to apprentice myself to this amazing body of poetry.” That kind of humility is rare in a world of large egos.

In Time and Materials, several poems (“For Czesław Miłosz in Krakow,” “Czesław Miłosz: In Memoriam”) were dedicated to Miłosz. Among the 40 pages of new poems, I found this one, “After Coleridge and for Miłosz: Late July”:

“… I think of the old man’s

dark study jammed with books in seven languages

as the headquarters of his military campaign

against nothingness. Immense egoism in it,

of course, the narcissism of a wound,

but actual making, actual work. One of the things

he believed was that our poems could be better

than our motives. …”

I wonder which “dark study” he is remembering: the comparatively airy one in Kraków, which had been tidied up by Angieszka Kosińska by the time I saw it several years after his death; or the far more familiar Tudoresque cottage on Grizzly Peak Boulevard, a winding street in the Berkeley Hills that is now a legendary name to all Poles (perhaps the best-known American street in Poland)? They both look curiously the same — both emphasized what Richard Lourie, in my forthcoming volume, called a premiere architectural virtue for Miłosz — “coziness.”

Curiously enough, the Grizzly Peak dwelling was bought by Miłosz’s friend, Mark Danner.

Tags: Czeslaw Milosz, Mark Danner, Richard Lourie, Robert Hass

September 12th, 2010 at 11:58 am

I’ve marked my calendar to buy the book when it comes out, November 2010….

September 17th, 2010 at 7:45 am

Title…

What a great post!…