I’ve always loved Vikram Seth’s novel-in-verse The Golden Gate, ever since it first came out in 1986. A dozen years later, I interviewed Seth in London – article here. Now the book is coming to Stanford, in its operatic incarnation. Here’s what I wrote for the Stanford News Service:

The homecoming is long overdue: The Golden Gate, Vikram Seth’s 1986 novel-in-verse, was born among Stanford’s sandstone buildings and palm trees. Now the Bay Area will have a chance to hear highlights of composer Conrad Cummings’ opera of the novel.

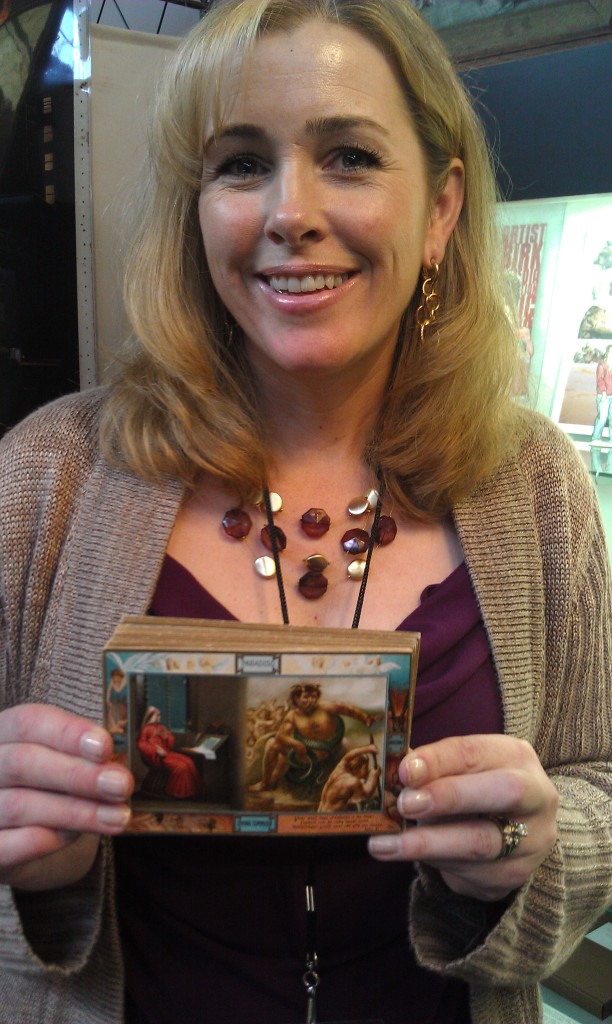

Phil (Kevin Burdette) reassures his son Paul (Elliot Kahn) in “The Golden Gate”

A multimedia presentation at the new Bing Concert Hall Studio at 8 p.m. Thursday, May 30, will include readings of Seth’s verse by current Stegner Fellows and Stanford students, a video of a 2010 staged workshop of the opera at Lincoln Center and a discussion with Cummings. John Henry Davis, who directed the Lincoln Center workshop production, is also directing the Stanford program. Seth will provide a video welcome.

“It’s beautiful, compelling, powerful – and it’s a production that deserves to be seen in the Bay Area,” said English Professor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, producer of the program, “From Lyric Novel to Lyric Stage.”

The event is sponsored by the Department English and its Creative Writing Program, the American Studies Program and the Stanford Arts Institute. The event is sold out, but unfilled seats will be released at 7:45 p.m. before the program begins.

The ‘Great Californian Novel’

San Francisco native Cummings, who teaches at Juilliard, discovered The Golden Gate soon after it was published and was hooked by “that special magical nostalgia I feel for my hometown San Francisco: the magic of the vistas, the feeling of the air, the presence of the ocean, the sense of space, and a certain sense of grandeur and personal emotion.”

In his book, Seth deprecated his foray in formal sonnets as “this whole passé extravaganza,” but he received rare accolades. The late Gore Vidal, who could be notoriously stinting of praise, wrote, “Although we have been spared, so far, the Great American Novel, it is good to know that the Great Californian Novel has been written, in verse (and why not?): The Golden Gate gives great joy.”

Conrad Cummings

Here’s how it began. In the 1980s, the graduate student from Calcutta, working on his doctorate in economics, was crunching data on Chinese villages. He crawled out one dawn from the basement of the Center for Educational Research at Stanford, where computer time was cheapest.

It was usual for Seth to unlock his bike as the raccoons were emerging from sewer gratings, but this time it was so late – or so early – that the Stanford Bookstore was just opening its doors at 7 a.m. Seth ducked in for a break and emerged with the book that would change his life: Charles Johnston’s new verse translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

What followed was a miracle: For more than a year, Seth feverishly wrote about 600 lines of verse a month of Pushkin-style sonnets. Seth, who had been a Stegner Fellow in 1977-78, used the Russian bard’s swift tetrameter, not pentameter, lines, along with a complicated rhyme scheme involving masculine and feminine endings, and also including Pushkin’s characteristic first-person digressions.

Seth wrote of harvesting olives on Campus Drive, lingering in the old Printers Inc bookshop café on California Avenue in Palo Alto and attending a concert at Stanford’s Dinkelspiel Auditorium. He wrote of San Francisco’s Coit Tower and Caffe Trieste – and, of course, the landmark Golden Gate Bridge, described in the libretto:

High-built, red-gold, with their long span

– The most majestic spun by man –

Whose threads of steel through mists and showers,

Wind, spray, and the momentous roar

Of ocean storms, link shore to shore.

Not all of the local events and places made it to Cummings’ opera, which the composer said “needed to be intimate and concentrated … to focus on the intense way lives interlaced with each other.” The opera follows the tightly bound fates of five Bay Area professionals, whose loves and lives sing through Seth’s inventive verse.

“Conrad loves the novel, and it shows – you can hear it,” said Chiyuma Elliott, the Stegner Fellow who coordinated the readings for the event. “It’s risky working with contemporary authors – it’s so easy to offend someone with the way you’ve reimagined their work. I think it says a lot that Seth is participating in this opera project and is excited about the ways his book is being recreated on stage.”

But how to turn Seth’s verbal music into sound?

The birth of an opera

Vikram Seth

Speaking from his New York City home, Cummings described how the opera was born. In the mid-1980s, Cummings was an artist at the Djerassi Foundation in the wooded hills above Woodside, Calif. Charles Martin, a poet and fellow resident who had just received Seth’s novel in manuscript, advised Cummings to keep an eye out for its publication. Cummings found the book a year or so later in New York and couldn’t put it down.

Cummings told his Russian mother in San Francisco about the book “because she’s a fan of Pushkin.”

“She told me she knew all about it,” Cummings said. “That she’d met Vikram at a reading of Golden Gate at City Lights Bookstore a few days before, and that he was coming to her house to hear her readEugene Onegin in Russian.” It was as good as an introduction.

Seth gave Cummings permission to use lines from The Golden Gate in a concert piece commissioned by the San Francisco Opera Center for the Schwabacher Debut Recital Series. Called “Fragments from The Golden Gate,” the piece was favorably reviewed in the San Francisco Chronicle when it premiered in December 1986, only half a year after the novel was published.

But Seth still hadn’t heard it. That part of the story picks up again in 1987 at the Djerassi Foundation, where this time Seth was in residence.

Cummings drove up the treacherous, twisty roads and fog-shrouded hills above Woodside to meet his collaborator at last. Cummings recalled the two of them, crouched over the cassette player in Cummings’ parked car at the foundation, listening to “Fragments.” Seth was pleased.

The opera was born two decades later. Opera News named it one of the best operas of the new century, and Stephen Smith of the New York Times praised it.

But it was still far from the place that gave it birth. Enter Fishkin, who championed its arrival at Stanford. “The story of my interest isn’t complicated,” she said. “Ever since I saw it at Lincoln Center, I wanted to bring it here. The Stanford connections made it perfect for the first year of the Bing Concert Hall.”

The “uncomplicated” part was born of friendship: Fishkin has been friends with Cummings since they were in the same residential college at Yale, decades ago. Now Fishkin lives in Cummings’ native land, and Cummings is the returning son. And Golden Gate has come home at last.

How often do you see volleyball team chatting with deans, Taiko drummers mingling with landscape gardiners, medical researchers in a tête-à-tête with major donors? “It was what a university community should be. That, to me, was moving,” said dancer Aleta Hayes, one of the performers for last night’s The Symphonic Body (we wrote about the event here.) And she was right.

How often do you see volleyball team chatting with deans, Taiko drummers mingling with landscape gardiners, medical researchers in a tête-à-tête with major donors? “It was what a university community should be. That, to me, was moving,” said dancer Aleta Hayes, one of the performers for last night’s The Symphonic Body (we wrote about the event here.) And she was right. Did anything surprise the cast about the performance? “I was surprised that I was in it,” admitted Associate Dean Debra Satz, to laughter.

Did anything surprise the cast about the performance? “I was surprised that I was in it,” admitted Associate Dean Debra Satz, to laughter.