Today would have been the Joseph Brodsky‘s 74th birthday. We laid the ground for the celebrations a few days ago with a post about the Nobel poet’s metaphysical experiences. Here are a few memories from two important friends.

Today would have been the Joseph Brodsky‘s 74th birthday. We laid the ground for the celebrations a few days ago with a post about the Nobel poet’s metaphysical experiences. Here are a few memories from two important friends.

Author Sven Birkerts of The Gutenberg Elegies, was managing a secondhand and rare bookstore in Ann Arbor when the poet befriended him. His mini-memoir matches my own recollections. Here’s what he wrote over Post Road Magazine:

At this time, back in the mid-1970s, Brodsky still had the air of an enfant terrible. Impatient, aggressive, chain-smoking cigarettes, he liked creating dispute for its own sake. Suggest white and he would insist black. Admit an admiration—unless it was for one of his idols—like Auden or Lowell or Milosz—and he would overturn the opinion. “Minor,” he would say of some eminence I mentioned. Or: “The man is an idiot.” At first I did not understand the workings of this compulsion, and as we talked, drinking cup after cup of black coffee, I grew despondent. Here was my chance to meet the poet I had admired for so long, and I could say nothing right. Yet for all that, he seemed in no hurry to leave.

I would like to say that by the end of that long afternoon we had become friends, intimates, but that would not be true. I was, I think, too young and callow; I did not offer enough ground for real exchange. Instead, Brodsky assumed a fond, almost paternal role with me, teasing, chiding, offering suggestions about books. A limit was set. I did not feel that I was getting close to the turbulent soul that wrote the poems.

From that time on, though, we did stay in contact. Brodsky would suddenly show up in the bookstore, searching for some book of poems. On several occasions, too, he handed me the typescript of some essay he was working on for the New York Review of Books, asking if I would check over his English. The task would invariably keep me at my desk for hours, for the fact is that brilliant and inflammatory as his insights were, the prose at this stage was a bramble patch—English deployed as if it were an inflected language.

From that time on, though, we did stay in contact. Brodsky would suddenly show up in the bookstore, searching for some book of poems. On several occasions, too, he handed me the typescript of some essay he was working on for the New York Review of Books, asking if I would check over his English. The task would invariably keep me at my desk for hours, for the fact is that brilliant and inflammatory as his insights were, the prose at this stage was a bramble patch—English deployed as if it were an inflected language.

Once, I remember, I stayed up much of the night, recasting sentence by sentence his discussion of the Greek poet Cavafy, finally typing the whole thing over afresh. When I handed the piece to him the next day, he quickly glanced down the page, smiled his wicked sultan smile, and put the whole bundle in an envelope to mail. I never found out what he thought of my deeply deliberated interventions.

Read the rest here.

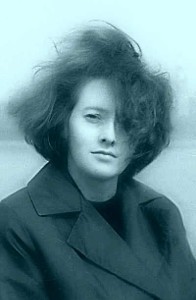

Over on a Russian site, Yuri Lepsky interviewed the Slavic scholar Faith Wigzell, who offered her first comments ever on the poet she met in the 1960s in Leningrad in “Loving, Leaving and Living.” She is the dedicatee of several poems, including “A Song to No Music” and “On Washerwoman Bridge.” According to Lepsky, “In the fifteen years since the poet’s death, she has published nothing about her friendship with him nor has she given any interviews on the subject nor published their correspondence. She has also refrained from commenting on the poems he dedicated to her.”

An excerpt:

– How did you meet Brodsky? What kind of first impression did he make on you?

– I believe it was March 1968. I had come to Leningrad for a six-week research visit, connected with my PhD at London University. … I arrived in Leningrad and straight away phoned my old friends Romas and Elia Katilius. Back in 1963-64 I was studying in Leningrad and it was then that I met the Katiliuses and Diana Abaeva, later to become Diana Myers and to work with me at London University. But that would come later.

It was back then, in the early 1960s, that we met and became friends. They were wonderful people – kind, engaging, loving poetry and art, and saw the Soviet government for what it was worth. They were scientists: Romas was a theoretical physicist at the semiconductor institute. Diana, on the other hand, was in the humanities’ field.

So, in short, I called the Katiliuses; they were very pleased and invited me over that evening. I went of course to their enormous room in a communal apartment on Tchaikovsky Street… But apart from my friends I there found a young man whom I had not previously met. He immediately attracted my attention.

– Firstly, he had this very unusual smile.

– What do you mean by unusual?

– How can I put it? It was a shy or, more precisely, a timid smile. Yes, yes, timid. And his voice…

– His voice?

– Well, it was something special… Never since then have I encountered such a voice. When he read his poetry his voice made an astonishing impression …

– And that was Brodsky?

– And that was Brodsky. It turned out that he had been friendly with the Katiliuses for a long time, and with Diana as well. The Katiliuses had a young child, so guests could not overstay their welcome. Late in the evening Joseph and I went out on Tchaikovsky Street, and he walked me back to the hotel. And so that’s how it all began.

– And you spoke about literature, of course?

– Not only, not only… (Faith laughs) As it turns out Joseph and I had another friend in common – Tolya Naiman. When I found out, I decided to give them both a present. I had brought with me from London a large bottle, a litre I think, of whisky. At that time in Russia whisky wasn’t to be found in ordinary shops. They were more than delighted to accept, but what happened next seemed to me downright horrible: the two of them proceeded to drink the entire bottle in the course of the evening. I was absolutely stunned. I asked: why did you drink the whole bottle? They just shrugged.

* * *

When her six weeks in Leningrad had come to an end and she had to go home, to London, it turned out that in addition to new impressions, research material and attractive souvenirs, she had packed something much more serious: an offer of heart and hand from the poet Joseph Brodsky.

When her six weeks in Leningrad had come to an end and she had to go home, to London, it turned out that in addition to new impressions, research material and attractive souvenirs, she had packed something much more serious: an offer of heart and hand from the poet Joseph Brodsky.

She returned to London and four years later married an American who lived in England. In 1972, when Brodsky was expelled from the USSR, he flew to London together with the great W.H. Auden for an international poetry festival. Faith was expecting her first child. Seeing her pregnant was a shock for Brodsky. She subsequently tried to keep their meetings to a minimum, so as not to cause him any distress.

* * *

– How do you relate to the poems which he dedicated to you: are they just Brodsky’s poems or are they poetic letters to Faith Wigzell?

– I cannot see them as simply Brodsky’s poems. I read them for myself.

– Above all else, I like the poems he wrote in Russia, in Leningrad and in Norenskaya. The period when he began to translate John Donne.

– Which of his essays do you like?

– What he wrote in Venice. Watermark.

– Have you seen his grave on the isle San Michele of Venice?

– No, I haven’t. Actually, I have only been to his beloved Venice once, when I was young.

– I once happened to visit San Michele when Venice was besieged by a snowstorm and Brodsky’s gravestone was covered by a big pile of snow, just like back in his beloved Leningrad…

– Yes, yes, he loved snow very much, big snowdrifts in particular…

Read the whole thing here.

Tags: "joseph brodsky", Faith Wigzell, Ramūnas Katilius, Sven Birkerts