Jane in Marin, writing. (Photo: Adam Phillips)

“At a certain stage, I realized a life is written in indelible ink.” Jane Hirshfield made an appearance at Kepler’s Books on Tuesday evening – and I know just what she means.

“Certain doors close,” she said. “It’s too late to be a bronco rider” – not that she ever wanted to be, she quickly added.

I’ve tried explaining this realization to friends. It’s not that there won’t be big surprises, new beginnings, unexpected turns, but I know I’ll never be a neurosurgeon – not that I wanted to be. Or an astronaut. When one enters the harvest period of life, one will reap not only as but where one has sown – a lifetime of planting fields of wheat won’t yield cabbages and thyme. A life with a pen … or a computer screen … means one won’t be a ballerina. This is hard to explain to the young ‘uns, for whom life and hope and joy is a world of almost endless possibilities – they may have ten children, or none. And everyone of them can still be a president. Yet I think today’s youth suffers greatly from unlimited possibility, and the uncertainty and burdens it brings – especially in modern Western culture, where we task our children with the creation of a whole life by the time they’re twenty or so.

There is a profound peace in doing the chosen thing well, and continuing to pick the fruit from efforts long made. It’s akin to the ideas percolating in a poet’s head and verse – “It changes, but only more into the person.” We become more and more ourselves. I’m happy to know my Zen friend Jane is a fellow traveler to the same psychological city. As she writes in the last line of one of her poems: “There was no other life.”

That realization permeates her new collection, The Beauty (Knopf), in such poems as “Perspective: An Assay,” “My Life was the Size of My Life,” “In My Wallet I Carry a Card,” “My Sandwich,” as well as “A Cottony Fate,” quoted above. (The Beauty was named a “best book of the year” by Amazon.)

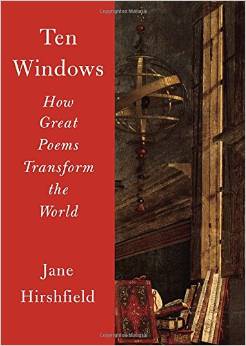

“Good art is a truing of vision, in the way a saw is trued in the saw shop, to cut more cleanly,” she writes in the preface of Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World (Knopf), a book of essays published at the same time as The Beauty (it was named by Publishers Weekly a “pick of the week”): “It is also a changing. Entering a good poem, a person feels, tastes, hears, and thinks in altered ways. Why ask art into a life at all, if not to be transformed and enlarged by its presence and mysterious means? Some hunger for more is in us – more range, more depth, more feeling; more associative freedom, more beauty. More perplexity and more friction of interest. More prismatic grief and unstunted delight, more longing, more darkness. More saturation and permeability in knowing our own existence as also the existence of others. More capacity to be astonished. Art adds to the sum of the lives we would have, were it possible to live without it. And by changing selves, one by one, art changes also the outer world that selves create and share.”

During a conversation at Kepler’s with poet Ellen Bass, she said finds poetry easier than prose – she has had eighteen years between volumes of essays; not so with writing poems, although “it’s not like I’m knocking them out like pancakes,” she said. While she considers herself a private person, and not at all a confessional or autobiographical writer, she said her poems are “completely nude portraits – but at the level of an X-ray.”

During a conversation at Kepler’s with poet Ellen Bass, she said finds poetry easier than prose – she has had eighteen years between volumes of essays; not so with writing poems, although “it’s not like I’m knocking them out like pancakes,” she said. While she considers herself a private person, and not at all a confessional or autobiographical writer, she said her poems are “completely nude portraits – but at the level of an X-ray.”

“Poems are not about expression. Poems are about making a discovery – not about what you really know and feel,” but rather weaving a basket that will carry “unknowable things.”

“Life is an unsolvable mathematical problem – and a lot of the wonderful and technological way of looking at things,” she said, trains us for a life in which there is “a single, correct answer.” If you’re working on the rings for a Challenger spacecraft, for example, “there is one correct answer and you better get it right.” But will it tell you why you want to travel to Mars in the first place? Can we get to the root of human aspiration and sorrow? Why can’t we have both?

“Why can’t we find the astonishment? Why can’t we find the precision?” she asked. She spoke of the opening poem of her new collection, “Fado” – which is a Portuguese song of longing and loss and the sea and (she learned later) the word also means “fate.” She described the perplexing process of its creation, “I have no idea where the fado singer comes from. Why is the woman in a wheelchair? She was completely unlimited by her situation.” As for the quarter and dove the or trickster finds on the girl, “Even if you know it’s a trick, it’s still a dove. It flies off. You can buy something with the quarter.”

Precision and uncertainty, uncertainty and solace: “There’s a way to feel alright with that, and not be undone by that.” At “Fado”‘s end, “what trembles in the pan has something of the uncertain. That’s what a poem does.”

.

Fado

A man reaches close

A man reaches close

and lifts a quarter

from inside a girl’s ear,

from her hands takes a dove

she didn’t know was there.

Which amazes more,

you may wonder:

the quarter’s serrated murmur

against the thumb

or the dove’s knuckled silence?

That he found them,

or that she never had,

or that in Portugal,

this same half-stopped moment,

it’s almost dawn,

and a woman in a wheelchair

is singing a fado

that puts every life in the room

on one pan of a scale,

itself on the other,

and the copper bowls balance.

Tags: Ellen Bass, Jane Hirshfield