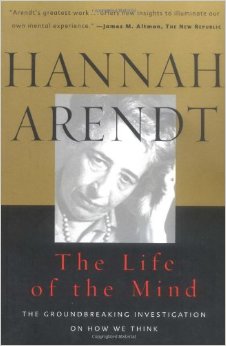

In her last, unfinished book, The Life of the Mind, Hannah Arendt returned to the subject of her earlier Eichmann in Jerusalem: The Banality of Evil. She concluded that the besetting sin of Eichmann “was something entirely negative: it was not stupidity but thoughtlessness.”

In her last, unfinished book, The Life of the Mind, Hannah Arendt returned to the subject of her earlier Eichmann in Jerusalem: The Banality of Evil. She concluded that the besetting sin of Eichmann “was something entirely negative: it was not stupidity but thoughtlessness.”

In the Time Higher Education Supplement, Jon Nixon discusses Arendt, the role of universities, “worldly thinking,” and amor mundi:

The Eichmann case raised a crucial question for Arendt: “Could the activity of thinking as such, the habit of examining whatever happens to come to pass or to attract attention, regardless of results and specific content, could this activity be among the conditions that make men abstain from evil-doing or even actually ‘condition’ them against it?” Arendt’s question arose in large part from her experience of totalitarianism, but also from her experience of political oppression under 1950s McCarthyism in the US and more generally from the ideological battle lines that defined the Cold War. She also viewed with increasing concern the unthinking consumerism and the assumption of ever increasing affluence that fuelled the American Dream prior to the stock market crash of 1973 and the oil crisis that followed later that year. Neither Hitler’s Nazism nor Stalin’s communism had, it would seem, exhausted the full potential of totalitarianism. So, the question remained urgent and pressing even within the heartlands of the democratic superpower of which she was now a citizen.

The Life of the Mind provides a tentatively affirmative response to that question: in so far as the activity of thinking requires us “to stop and think”, it may condition us against evil-doing. But this last work also raises – by implication at least – a more difficult question: could the activity of thinking not only condition us against evil-doing but predispose us towards right action? Here Arendt’s response is less clear, partly because it hinges on her suspicion of “pure thought” and partly because the final and crucial section of The Life of the Mind remained unwritten. What is clear is her insistence that without thinking that reaches out in dialogue to others there can be no informed judgement, no moral agency and no possibility of collective action – no “care for the world”.

Education was, for Arendt, an expression of that care – “the point at which”, as she wrote in her 1954 essay on “The Crisis in Education”, “we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it”. Education provides us with a protected space within which to think against the grain of received opinion: a space to question and challenge, to imagine the world from different standpoints and perspectives, to reflect upon ourselves in relation to others and, in so doing, to understand what it means to “assume responsibility”. She had observed at first hand how such opinion can solidify into ideology. For her, thinking was diametrically opposed to ideology: ideology demands assent, is founded on certainty, and determines our behaviours within fixed horizons of expectation; thinking, on the other hand, requires dissent, dwells in uncertainty and expands our horizons by acknowledging our agency. It is the task of education – and therefore of the university – to ensure that a space for such thinking remains open and accessible.

Read the whole thing here. It’s worth thinking about as we redefine education and the humanities in collective and consumeristic ways. It’s also worth pondering as we head inexorably into an election season already riddled with clichés, banality, repetition, and derivative thinking.

Tags: "Hannah Arendt", Jon Nixon

May 2nd, 2015 at 2:11 pm

I enjoy your blog, especially your coverage of the West coast. The take on Arendt is interesting, but a lot of “thinking” people went along quite well with Hitler. When I hear my German friends exclaim, about professors and other smart people, “How could they have gone along with Hitler?” I reply, maybe it was because they were smart! I don’t think Germany represents a singular case. As “intellectuals” we have to be careful about imputing “thoughtfulness” to ourselves. As a person who grew up in Middle America I have always taken umbrage at the expression “thoughtless consumerism.” Maybe “unthinking” would be better? In any case, in my view, Eichmann knew what he was doing; he wasn’t thoughtless at all. Academics are not above “derivative thinking.”