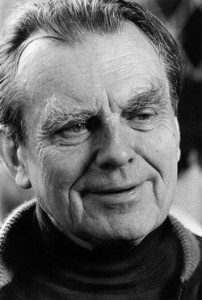

Birthday boy.

Today is Czesław Miłosz‘s birthday – his 104th. To celebrate the occasion, I revisited his Nobel lecture. Oh, and I baked him a little white cake; see below. And also, a photo at bottom from where it all began, at his birthplace in Šeteniai.

In 1980, Miłosz gave one of the all-time great Nobel addresses. A few excerpts to prove it:

“Every poet depends upon generations who wrote in his native tongue; he inherits styles and forms elaborated by those who lived before him. At the same time, though, he feels that those old means of expression are not adequate to his own experience. When adapting himself, he hears an internal voice that warns him against mask and disguise. But when rebelling, he falls in turn into dependence upon his contemporaries, various movements of the avant-garde. Alas, it is enough for him to publish his first volume of poems, to find himself entrapped. For hardly has the print dried, when that work, which seemed to him the most personal, appears to be enmeshed in the style of another. The only way to counter an obscure remorse is to continue searching and to publish a new book, but then everything repeats itself, so there is no end to that chase. And it may happen that leaving books behind as if they were dry snake skins, in a constant escape forward from what has been done in the past, he receives the Nobel Prize.”

“What is this enigmatic impulse that does not allow one to settle down in the achieved, the finished? I think it is a quest for reality. I give to this word its naive and solemn meaning, a meaning having nothing to do with philosophical debates of the last few centuries. It is the Earth as seen by Nils from the back of the gander and by the author of the Latin ode from the back of Pegasus. Undoubtedly, that Earth is and her riches cannot be exhausted by any description. To make such an assertion means to reject in advance a question we often hear today: ‘What is reality?’, for it is the same as the question of Pontius Pilate: ‘What is truth?’ If among pairs of opposites which we use every day, the opposition of life and death has such an importance, no less importance should be ascribed to the oppositions of truth and falsehood, of reality and illusion.”

***

“The thick walls of our ancient university.” (Photo: C.L. Haven)

“It is good to be born in a small country where Nature was on a human scale, where various languages and religions cohabited for centuries. I have in mind Lithuania, a country of myths and of poetry. My family already in the Sixteenth Century spoke Polish, just as many families in Finland spoke Swedish and in Ireland – English; so I am a Polish, not a Lithuanian, poet. But the landscapes and perhaps the spirits of Lithuania have never abandoned me. It is good in childhood to hear words of Latin liturgy, to translate Ovid in high school, to receive a good training in Roman Catholic dogmatics and apologetics. It is a blessing if one receives from fate school and university studies in such a city as Vilno. A bizarre city of baroque architecture transplanted to northern forests and of history fixed in every stone, a city of forty Roman Catholic churches and of numerous synagogues. In those days the Jews called it a Jerusalem of the North. Only when teaching in America did I fully realize how much I had absorbed from the thick walls of our ancient university, from formulas of Roman law learned by heart, from history and literature of old Poland, both of which surprise young Americans by their specific features: an indulgent anarchy, a humor disarming fierce quarrels, a sense of organic community, a mistrust of any centralized authority.”

***

“Our planet that gets smaller every year, with its fantastic proliferation of mass media, is witnessing a process that escapes definition, characterized by a refusal to remember. Certainly, the illiterates of past centuries, then an enormous majority of mankind, knew little of the history of their respective countries and of their civilization. In the minds of modern illiterates, however, who know how to read and write and even teach in schools and at universities, history is present but blurred, in a state of strange confusion; Molière becomes a contemporary of Napoleon, Voltaire, a contemporary of Lenin. Also, events of the last decades, of such primary importance that knowledge or ignorance of them will be decisive for the future of mankind, move away, grow pale, lose all consistency as if Frederic Nietzsche‘s prediction of European nihilism found a literal fulfillment. ‘The eye of a nihilist,’ he wrote in 1887, ‘is unfaithful to his memories: it allows them to drop, to lose their leaves;… And what he does not do for himself, he also does not do for the whole past of mankind: he lets it drop’ We are surrounded today by fictions about the past, contrary to common sense and to an elementary perception of good and evil. As The Los Angeles Times recently stated, the number of books in various languages which deny that the Holocaust ever took place, that it was invented by Jewish propaganda, has exceeded one hundred. If such an insanity is possible, is a complete loss of memory as a permanent state of mind improbable? And would it not present a danger more grave than genetic engineering or poisoning of the natural environment?”

“For the poet of the ‘other Europe’ the events embraced by the name of the Holocaust are a reality, so close in time that he cannot hope to liberate himself from their remembrance unless, perhaps, by translating the Psalms of David. He feels anxiety, though, when the meaning of the word Holocaust undergoes gradual modifications, so that the word begins to belong to the history of the Jews exclusively, as if among the victims there were not also millions of Poles, Russians, Ukrainians and prisoners of other nationalities. He feels anxiety, for he senses in this a foreboding of a not distant future when history will be reduced to what appears on television, while the truth, as it is too complicated, will be buried in the archives, if not totally annihilated.”

“For the poet of the ‘other Europe’ the events embraced by the name of the Holocaust are a reality, so close in time that he cannot hope to liberate himself from their remembrance unless, perhaps, by translating the Psalms of David. He feels anxiety, though, when the meaning of the word Holocaust undergoes gradual modifications, so that the word begins to belong to the history of the Jews exclusively, as if among the victims there were not also millions of Poles, Russians, Ukrainians and prisoners of other nationalities. He feels anxiety, for he senses in this a foreboding of a not distant future when history will be reduced to what appears on television, while the truth, as it is too complicated, will be buried in the archives, if not totally annihilated.”

***

“Complaints of peoples, pacts more treacherous than those we read about in Thucydides, the shape of a maple leaf, sunrises and sunsets over the ocean, the whole fabric of causes and effects, whether we call it Nature or History, points towards, I believe, another hidden reality, impenetrable, though exerting a powerful attraction that is the central driving force of all art and science.”

“Our century draws to its close, and largely thanks to those influences I would not dare to curse it, for it has also been a century of faith and hope. A profound transformation, of which we are hardly aware, because we are a part of it, has been taking place, coming to the surface from time to time in phenomena that provoke general astonishment.”

***

You can read the whole thing here. Regarding the photograph below: I had the great good fortune in 2011 to visit Miłosz’s birthplace in the rural Lithuanian village of Šeteniai. And yes, it is as idyllic as he said it was – it reminded me of the woods and deep green colors of Michigan. I took this photo on the former Miłosz family estate, overlooking the river. The fishers called out to ask if we had permission to photograph them. Yes, one of us shouted back, there was a journalist in the group. They laughed, thinking it was a joke.

The perfect place to be born. (Photo: C.L. Haven)

Tags: Czeslaw Milosz