Our 2012 post, Enjoy Les Misérables. But please get the history straight is still getting comments – close to 150 of them now. And I also get some private correspondence. One recent email from a kind reader told me of a Smithsonian Magazine article featuring Victor Hugo‘s Paris – but only one of the locales it featured (unless you count the Jardin du Luxembourg) had any specific associations with his masterpiece. From The Smithsonian:

“A sewer is a cynic. It tells all.”

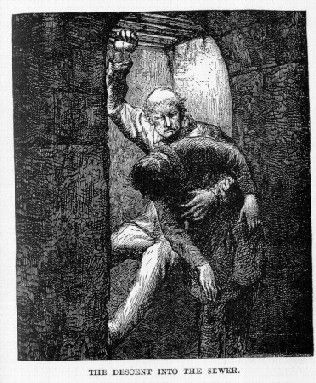

Paris’s underworld features heavily in Les Misérables, most famously its sewers, which once branched for a hundred miles beneath the city’s cobbled streets. It is here that Jean Valjean escapes in one of the book’s most dramatic scenes, fleeing the barricade with a wounded Marius on his back. “An abrupt fall into a cavern; a disappearance into the secret trapdoor of Paris; to quit that street where death was on every side, for that sort of sepulchre where there was life, was a strange instant,” writes Hugo. Baron Haussmann’s overhaul left few stones unturned, including the black, squalid sewer tunnels of Hugo’s day. But, visitors to the city can still catch a glimpse of Paris’ underground at the Musée des Égouts, which offers hour-long tours chronicling the sewer system’s modern development—no hazmat suit required.

That journey of clicks took me he Musée des Égouts on the Quai d’Orsay in Paris – it has a museum and a website.

A non-click journey to my library returned me to Hugo’s massive novel. Here’s what he had to say about the sewers where Jean Valjean escapes carrying his wounded son-in-law-to-be, Marius Pontmercy, who has had his brief and unsuccessful role in the 1830 uprising. About 1,260 pages into the book, the French maestro writes:

The sewer is the conscience of the city. All things converge into it and are confronted with one another. In this lurid place there is darkness, but there are no secrets. Each thing has its real form, or at least its definitive form. It can be said for the garbage heap that it is no liar. … All the uncleanliness of civilization, once it is out of service, falls into this pit of truth, where the immense social slippage is brought to an end. It is swallowed up, but it is displayed in it. The pell-mell is a confusion. Here, no more false appearances, no possible plastering, filth takes off its shirt, absolute nakedness, rout of illusions and mirages, nothing more but what is, wearing the sinister face of what is ending. Reality and disappearance. Here the stump of a bottle confesses drunkenness, a basket handle tells of domestic life; here, the apple core that has had literary opinions becomes again an apple core; the spittle of Caïaphas encounters Falstaff’s vomit, the louis d’or that comes from the gambling house jostles the nail trailing the suicide’s bit of rope, a livid fetus rolls by wrapped in spangles that danced at the Opéra last Mardi Gras, a cap that has judged men wallows near a rottenness that was one of Peggy’s petticoats; it is more than brotherhood, it is closest intimacy. All that used to be painted is besmirched. The last veil is rent. A sewer is a cynic. It tells all.

The sewer is the conscience of the city. All things converge into it and are confronted with one another. In this lurid place there is darkness, but there are no secrets. Each thing has its real form, or at least its definitive form. It can be said for the garbage heap that it is no liar. … All the uncleanliness of civilization, once it is out of service, falls into this pit of truth, where the immense social slippage is brought to an end. It is swallowed up, but it is displayed in it. The pell-mell is a confusion. Here, no more false appearances, no possible plastering, filth takes off its shirt, absolute nakedness, rout of illusions and mirages, nothing more but what is, wearing the sinister face of what is ending. Reality and disappearance. Here the stump of a bottle confesses drunkenness, a basket handle tells of domestic life; here, the apple core that has had literary opinions becomes again an apple core; the spittle of Caïaphas encounters Falstaff’s vomit, the louis d’or that comes from the gambling house jostles the nail trailing the suicide’s bit of rope, a livid fetus rolls by wrapped in spangles that danced at the Opéra last Mardi Gras, a cap that has judged men wallows near a rottenness that was one of Peggy’s petticoats; it is more than brotherhood, it is closest intimacy. All that used to be painted is besmirched. The last veil is rent. A sewer is a cynic. It tells all.

Thi sincerity of uncleanness pleases us, and it is a relief to the soul. When a man has spent his time on earth enduring the spectacle of the grand airs assumed by reasons of state, oaths, political wisdom, human justice, professional honesty, the necessities of position, incorruptible robes, it is a consolation to enter a sewer and see the slime that befits it.

Tags: Victor Hugo