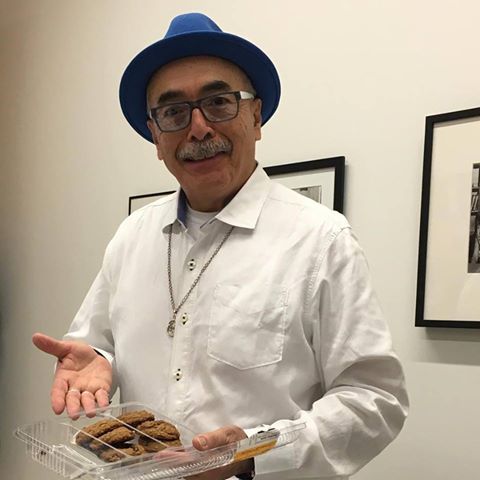

Herrera offering cookies at the Poetry Foundation (Photo: Don Share)

Last month, U.S. poet laureate Juan Felipe Herrera visited Stanford. We were still only two months into a new presidency. It was much on Herrera’s mind, and on the collective mind of the full house he had attracted to Cubberley Auditorium for a free-wheeling evening of reading, commentary, reflections, and audience participation.

He spoke of the United Farm Workers Movement – “those were my classrooms,” he said. He grew up in a different era, the era in the 1960s, where the vital question was: “Do you want to be in the classroom, or out in the streets, marching with people?” He remembered his “early occupied water tank poetry,” when he was director of the Centro Cultural de la Raza, headquartered in an occupied water tank in San Diego’s Balboa Park, which had been converted into an arts space.

He also referred to his time as a Stanford anthropology major: “I was sizzling on anthropology, sizzling on poetry – two major sizzles.” Of course we know which sizzle won.

“I was a Chicano on fire.” He still is. As poet laureate, he described meeting an 11-year-old who had written a poem about the children left behind because their parents had been deported. The story got a big round of applause, or perhaps the applause came when he said, “America! Stop deporting us!

He recalled saying “one thing they made sure – that we could never be authors” – that is, by prohibiting slaves from learning to read and write.

“You are the author. You are the author,” he told the audience.

From the director of Stanford’s Creative writing program, the Irish poet Eavan Boland, who gave an excellent (as usual) introduction:

As he traveled through those landscapes, in actuality and memory, he also explored the psyche of place, drawing into his work influences and affinities as far apart and yet as apposite as Allen Ginsberg and Luis Valdez.

And in all of these travels and writings he has been an innovative, restless stylist, in the words of in the New York Times becoming the creator of “a new hybrid art, part oral, part written, part English, part something else.”

It is the something else, perhaps, that makes us especially eager to hear him this evening. In an interview with NPR he recalled his childhood. As the son of Mexican farm workers, he followed them the San Joaquin and Salinas valleys,migrating as his parents did, seeking work. But when he remembered those years in an interview given to NPR he also spoke about their meaning. This is what he said:

It is the something else, perhaps, that makes us especially eager to hear him this evening. In an interview with NPR he recalled his childhood. As the son of Mexican farm workers, he followed them the San Joaquin and Salinas valleys,migrating as his parents did, seeking work. But when he remembered those years in an interview given to NPR he also spoke about their meaning. This is what he said:

“And those landscapes, you know, those are some deep landscapes of mountains and grape fields and barns and tractors; families gathering at night to have little celebrations in the mountains and aquamarine lakes way down below. So, see, all that is like living in literature every day.”

Juan Felipe Hererra’s words here provide a pathway into his achievement. The idea of a literary enterprise which is lived rather than learned is everywhere in his work. His words also remind us that the oldest life of poetry lies deep in its communal existence, in its companionable relation to a people, to a language, to the future of both. It also reminds us of the association of this writer with one of the true traditions of poetry, the poet’s refusal from Homer onwards to disown the adventures and sorrows of a people, and the artistic determination to draw their story into the dignity of remembrance and beautiful speech.

Tags: Eavan Boland, Juan Felipe Herrera