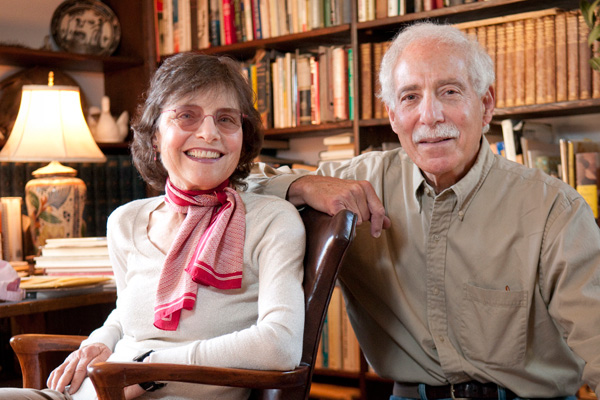

Mary Felstiner, with her late husband, translator and poet John Felstiner (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

Our post yesterday, “Psssst! She killed her grandfather” recounted the controversy surrounding a recently revealed confession of artist Charlotte Salomon, one of the great innovative artists of the last century, who was killed at Auschwitz. The “confession” detailed how she murdered her grandfather. But did she? I reached out to Mary Felstiner, the first historian and biographer of Salomon, author of To Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon In the Nazi Era (HarperCollins, UC Press), which was awarded the American Historical Association Prize in 1995.

In fact, she is working on an essay on this very subject.

Mary’s judicious thoughts about the startling revelation:

The book where the confession appears…

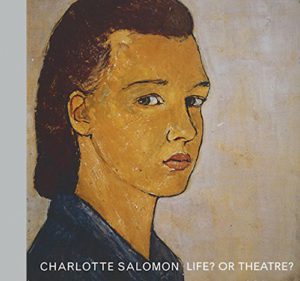

Charlotte Salomon has gained a considerable reputation in the last year: a major exhibition in Amsterdam; her artwork reproduced by Taschen, in German, French, and English; a stunning full-size art book published by Duckworth/Overlook, including the first translation and notes revealing new material; a capacious and profound work of art criticism by Griselda Pollock, published by Yale University Press. These have prompted riveting recent reviews in The New Yorker, London Review of Books, New York Review of Books, and Women’s Review of Books.

Charlotte Salomon’s 1941-42 artwork, Life? or Theater?, still astonishes onlookers, even in printed reproductions — her thousand-plus paintings create a new form, a visual operetta with staging and music and characters and political commentary. In addition, new interest in Charlotte Salomon has been stimulated by a multi-page painted “letter” she wrote in 1943. It was rediscovered in 2012, or rather, kept under wraps until 2012. Its content has proved shocking. Among deeper, more significant revelations, the artist – obliged to take care of her grandfather – rails against him, and then confesses to feeding him a morphine-based omelette as she writes the “letter.”

This rediscovered material has stretched new interpretations beyond previous historical, biographical, or art-critical accounts of the unprecedented artwork. It is now relabeled also as a story leading to murder by a victim of sexual abuse.

Was her confession truth or art?

A historian and biographer like myself, who decades ago located and interviewed many witnesses to Charlotte Salomon’s life, becomes concerned when interpretations rely principally on the paintings alone. For they are imaginative, theatrical, drawing on reality.

Neither inside or outside these paintings is there any direct evidence of either murder or abuse; and while such crimes are peculiarly hard to document in any specific case, the standard for non-evidentiary interpretation should be this: Are there significant numerous examples (say, of sexual threats and homicide within German Jewish families) from that time, place, and culture, and do these substantiate the interpretation? For instance, historians such as myself and Darcy Buerkle surrounded Charlotte Salomon’s artwork, which transmits a continuous theme of suicide, with serious archival research on suicide and secrecy in her time and place. Equivalent research would need to accompany the new material.

Personally, I tend to believe Charlotte Salomon wanted to put down her grandfather, but the act, if actual, was pressured by her historical context in 1943, and it’s not known if she succeeded in her fantasy or attempt. As for sexual abuse, she did paint one scene of attempted sexual abuse – by an unknown refugee on the road – so I am reluctant to accuse her grandfather without any direct word from the artist, either in an artwork that reveals other highly-charged family secrets, or in a “letter” revealing a more shameful and dangerous “confession.”

Tags: Charlotte Salomon, Mary Felstiner