A few months ago, Joy Harjo was named the first Native American U.S. poet laureate, and there was universal rejoicing in the land. According to the press release: “Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden appointed Joy Harjo as the 23rd Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress on June 19, 2019. Joy Harjo is the first Native American poet to serve in the position—she is an enrolled member of the Muscogee Creek Nation.”

But wait! Isn’t the Library of Congress overlooking someone rather important? From 1968-70, the position was held by William Jay Smith, a poet who was well known, but he died in his 90s, perhaps outliving his renown (insofar as poets every, really, have renown). On the other hand, his death is not ancient history – he died fairly recently, in 2015 (we wrote about it here; conscientious Book Haven readers will also remember an earlier post here.) He was in the news; his obituary was even in the New York Times, not a given for poets. He was so well known that Princess Grace of Monaco invited him to represent the United States at a Monaco poetry celebration.

But wait! Isn’t the Library of Congress overlooking someone rather important? From 1968-70, the position was held by William Jay Smith, a poet who was well known, but he died in his 90s, perhaps outliving his renown (insofar as poets every, really, have renown). On the other hand, his death is not ancient history – he died fairly recently, in 2015 (we wrote about it here; conscientious Book Haven readers will also remember an earlier post here.) He was in the news; his obituary was even in the New York Times, not a given for poets. He was so well known that Princess Grace of Monaco invited him to represent the United States at a Monaco poetry celebration.

His Choctaw heritage was hardly a secret – he was proud of it, and mentioned it at readings. He also wrote about it in perhaps his best-known book, The Cherokee Lottery, which recounts the 1828 “Trail of Tears,” which forcibly relocated his ancestors, along with a total of 18,000 Cherokees, Chickasaws, and Creeks as well, to Oklahoma from their native northern Georgia, where gold had been discovered and greed unleashed.

I remember him reading from this sequence of poems at the West Chester poetry conference, some years ago. That was the same conference where I met Richard Wilbur and his wife Charlee. The conjunction was not a coincidence, in fact the two poets were close friends, and lived near each other in Cummington, Massachusetts. So near that they picked up their Sunday New York Times editions from the same village shop. In fact, they had a tradition – whoever picked up their newspaper first would write scurrilous doggerel on the other’s. It was a tradition that continued for years.

I remember him reading from this sequence of poems at the West Chester poetry conference, some years ago. That was the same conference where I met Richard Wilbur and his wife Charlee. The conjunction was not a coincidence, in fact the two poets were close friends, and lived near each other in Cummington, Massachusetts. So near that they picked up their Sunday New York Times editions from the same village shop. In fact, they had a tradition – whoever picked up their newspaper first would write scurrilous doggerel on the other’s. It was a tradition that continued for years.

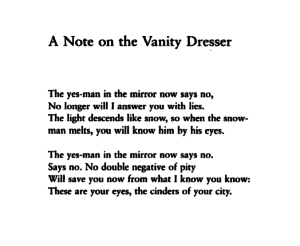

He also wrote the matchless poem “Note on the Vanity Dresser” above. It’s been called the most perfect symbolist poem in the English language. Only eight lines, and it’s endless.

So given this history, why the omission? Is it because, as some have suggested when I floated the subject on Twitter, they hoped to make a politically correct splash, and make it sound like poetry has crashed some sort of intersectional sound barrier? Or what? He is included in the Library of Congress’ own record of the laureate history, Poetry’s Catbird Seat: The Consultantship in Poetry in the English Language at the Library of Congress, 1937-1987. Weirdly, the book, which should be a public record, is not searchable on Google Books. We include the relevant pages below.

All congratulations to Joy Harjo – but let’s set the record straight.

Postscript: Since posting, I’ve learned that others have noticed this omission as well – Kay Day wrote about it here. Also, A.M. Juster raised the issue almost immediately on Twitter and directly with the Library of Congress. He is working on an article about it, forthcoming later this summer with Los Angeles Review of Books.

Post-postscript from Dana Gioia, former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts and former California Poet Laureate: “It does Joy Harjo no dishonor to acknowledge that one of her predecessors, William Jay Smith, had some Choctaw ancestry. Smith was proud of his background at a time – the 1930s – when the association gained him no advantage, especially in the racist milieu of his childhood. He did considerable genealogical research to establish a ancestry many generations back. It was a remote connection, though Smith plausibly felt it had manifested itself in his physical appearance, but it hardly seems unlikely. Many Americans have mixed and complicated ancestry, which should rightly be a source of pride.” See combox below. Incidentally, Dana describes himself as “100% non-Anglo” – Sicilian on his father’s side, and mixed Mexican and Native American ancestry on his mother’s side. So he knows a thing or two about “complicated ancestry.”

Tags: Joy Harjo, Richard Wilbur, William Jay Smith

July 6th, 2019 at 3:46 pm

It does Joy Harjo no dishonor to acknowledge that one of her predecessors, William Jay Smith, had some Choctaw ancestry. Smith was proud of his background at a time – the 1930s – when the association gained him no advantage, especially in the racist milieu of his childhood. He did considerable genealogical research to establish a ancestry many generations back. It was a remote connection, though Smith plausibly felt it had manifested itself in his physical appearance, but it hardly seems unlikely. Many Americans have mixed and complicated ancestry, which should rightly be a source of pride.