Today is James Baldwin‘s birthday. To celebrate, here’s a portion of “Letter from a Region of My Mind,” which appeared in The New Yorker on November 17, 1962 – and then Hannah Arendt‘s reply. In his essay, Baldwin concluded:

“When I was very young, and was dealing with my buddies in those wine- and urine-stained hallways, something in me wondered, What will happen to all that beauty? For black people, though I am aware that some of us, black and white, do not know it yet, are very beautiful. And when I sat at Elijah’s table and watched the baby, the women, and the men, and we talked about God’s – or Allah’s – vengeance, I wondered, when that vengeance was achieved, What will happen to all that beauty then? I could also see that the intransigence and ignorance of the white world might make that vengeance inevitable – a vengeance that does not really depend on, and cannot really be executed by, any person or organization, and that cannot be prevented by any police force or army: historical vengeance, a cosmic vengeance, based on the law that we recognize when we say, “Whatever goes up must come down.” And here we are, at the center of the arc, trapped in the gaudiest, most valuable, and most improbable water wheel the world has ever seen. Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we – and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others – do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!

“When I was very young, and was dealing with my buddies in those wine- and urine-stained hallways, something in me wondered, What will happen to all that beauty? For black people, though I am aware that some of us, black and white, do not know it yet, are very beautiful. And when I sat at Elijah’s table and watched the baby, the women, and the men, and we talked about God’s – or Allah’s – vengeance, I wondered, when that vengeance was achieved, What will happen to all that beauty then? I could also see that the intransigence and ignorance of the white world might make that vengeance inevitable – a vengeance that does not really depend on, and cannot really be executed by, any person or organization, and that cannot be prevented by any police force or army: historical vengeance, a cosmic vengeance, based on the law that we recognize when we say, “Whatever goes up must come down.” And here we are, at the center of the arc, trapped in the gaudiest, most valuable, and most improbable water wheel the world has ever seen. Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we – and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others – do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!

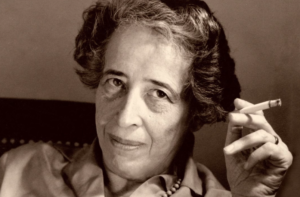

Here’s what Hannah Arendt, who knew him slightly, replied in a letter that is now at the Library of Congress:

November 21, 1962

Dear Mr. Baldwin:

Your article in the New Yorker is a political event of a very high order, I think; it certainly is an event in my understanding of what is involved in the Negro question. And since this is a question which concerns us all, I feel I am entitled to raise objections.

What frightened me in your essay was the gospel of love which you begin to preach at the end. In politics, love is a stranger, and when it intrudes upon it nothing is being achieved except hypocrisy. All the characteristics you stress in the Negro people: their beauty, their capacity for joy, their warmth, and their humanity, are well-known characteristics of all oppressed people. They grow out of suffering and they are the proudest possession of all pariahs. Unfortunately, they have never survived the hour of liberation by even five minutes. Hatred and love belong together, and they are both destructive; you can afford them only in the private and, as a people, only so long as you are not free.

What frightened me in your essay was the gospel of love which you begin to preach at the end. In politics, love is a stranger, and when it intrudes upon it nothing is being achieved except hypocrisy. All the characteristics you stress in the Negro people: their beauty, their capacity for joy, their warmth, and their humanity, are well-known characteristics of all oppressed people. They grow out of suffering and they are the proudest possession of all pariahs. Unfortunately, they have never survived the hour of liberation by even five minutes. Hatred and love belong together, and they are both destructive; you can afford them only in the private and, as a people, only so long as you are not free.

In sincere admiration,

cordially (that is, in case you remember that we know each other slightly) yours,

Tags: "Hannah Arendt", James Baldwin