Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odessa, an ancient Crimean city on the Black Sea. As a 4-year-old child, a doctor misdiagnosed his mumps as a flu, and as a result, he lost most of his hearing. He has written that, for him, Odessa is “a silent city, where the language is invisibly linked to my father’s lips moving as I watch his mouth repeat stories again and again. He turns away. The story stops.”

Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odessa, an ancient Crimean city on the Black Sea. As a 4-year-old child, a doctor misdiagnosed his mumps as a flu, and as a result, he lost most of his hearing. He has written that, for him, Odessa is “a silent city, where the language is invisibly linked to my father’s lips moving as I watch his mouth repeat stories again and again. He turns away. The story stops.”

The family emigrated to Rochester, New York, and after his father’s death in 1994, Kaminsky began to write poems in English. He explained in an interview with the Adirondack Review, “I chose English because no one in my family or friends knew it—no one I spoke to could read what I wrote. I myself did not know the language. It was a parallel reality, an insanely beautiful freedom. It still is.”

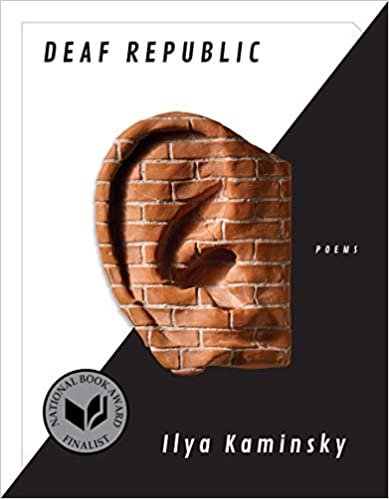

He is the author of last year’s acclaimed Deaf Republic, a poetry collection framed as a two-act play, which takes place in the fictional village of Vasenka.

An excerpt from Joe Dunthorne’s interview with him in the elegant White Review:

I come from the part of East Europe of which people usually say ‘Oh wow, everyone loves poetry in Russia, in Ukraine, so much that people come to football stadiums to hear poetry.’

That is bullshit.

Every great poet is a very private person who happens to write beautifully enough, powerfully enough, spell-bindingly enough that they can speak privately to many people at the same time. That to my mind is the definition of an original poet. Not play for the sake of mere play. And not a public pronouncement either, but a very private speech that the form teaches you how to partake in – and that becomes the reader’s own private speech.

***

It’s curious to me that in Western Europe, intellectuals, liberals, are so afraid of large metaphysical questions. I mean, maybe it’s because I was born in 1977: by the time my family left, it was already independent Ukraine. So all of my childhood and pretty much most of my adolescence was a time of the USSR falling apart. Everyone lost their salaries, pensions, etc. All the people’s assets became metaphysical because everything else that they knew was not there any more.

And many were happy. And many were not happy.

It’s not about a political position. It’s about a metaphysical position.

People were arguing until 4 a.m. about the purpose of life, about poetry, about what poets express these unanswerable questions. Who is better, Akhmatova or Tsvetaeva, who speaks best to our time, Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, those kind of questions. People really argued: who gives words to shape my unknown?

Reading in San Diego (Photo: Patty Mooney)

And then there was the shock of coming to the US and seeing deeply intelligent humans completely unengaged with all of that. It was weird. It is not polite to ask metaphysical questions in the USA. Few do it with strangers.

So, a friend, the wonderful novelist Katherine Towler and I just thought, okay, why not start interviewing people because it gave us a mask. If you’re doing an interview, you can ask whatever you want and it’s not impolite.

I still marvel about this: for some reason in American society, asking metaphysical questions is not polite. I don’t know why but that is the case.

So the interview project was interesting because some poets who shall not be named gave wonderful interviews but later decided not to be in the book for the same reason. That, too, is a reflection of a Western Society. I keep marvelling at that.

***

Any trace of thoughtfulness is completely wiped out and people who have the thoughts are refusing to engage.

In that way, I do believe that our intellectuals are in some ways responsible for what is happening right now in 2020: for not engaging with so many of our fellow countrymen. The end result is that the depth is taken away from the discourse. The discourse of ‘why am I on this planet’ is going to happen whether or not the intellectuals choose to participate in it. But depth of conversation might suffer should they choose not to participate. One sees that in the USA on a daily basis.

***

I think poets, when they write, they participate in that process physically. Some read the poems to themselves, yes. Many do. It’s got to be a physical activity. Language by definition is a production of a body: it’s a physical activity.

When I write I definitely speak to myself: I’m interested in the kind of intensity that language allows us to have, a kind of chant, incantation. There is a whole wonderful, beautiful world of performance, spoken word poetics. And it is something I respect very much but it’s not exactly what I’m after. What I am interested in is poets who, in reading aloud, continue the writing process.

So when I’m reading I often change words, but I can’t change too many words. So I change line breaks instead. Rarely is the line break the same as it is in the book. I change the accents a lot, I change emphasis a lot. So it gives me this room where I can still be a poet as opposed to a person who reads his poem, because otherwise I just get bored. I start watching a fly. But to read as if the poem is still being written, to use the mouth as a way to invent new line breaks, that is something that makes the public reading still interesting for me.

Read the whole thing here.

Tags: Ilya Kaminsky

October 5th, 2020 at 8:00 pm

Regarding the idea that metaphysical questions are impolite in the U.S., I’ve heard similar claims, though less tactfully stated, from immigrants and long-term visitors to the U.S. Most often, I’ve heard that Americans are politely evasive; one German told me a couple years ago that she finds most Americans, in her words, “as inscrutable as the Japanese.” Most of the people who say things like that, however, come from very homogeneous societies. My hunch is that in a society with the dizzying ethnic and religious diversity of the U.S., most thinking people who grew up here are wary of making assumptions about strangers or acquaintances. Kaminsky hopefully finds that he can have some pretty freewheeling conversations with people he knows well.

The other possibility is that many fairly intelligent American writers simply haven’t contemplated metaphysical questions about literature and are embarrassed when a more informed and earnest friend tries to engage them in conversation.

October 7th, 2020 at 5:16 pm

One of the sharpest of the philosophy professors I had in college said that Americans have no real bent for philosophy, by which I believe he meant metaphysical philosophy and the tradition that came out of German Idealism (not counting the part that was watered down into pragmatism). Anyway, after forty-odd years, that’s what I remember him saying.

“And what have Russian boys been doing up till now, some of them, I mean? In this stinking tavern, for instance, here, they meet and sit down

in a corner. They’ve never met in their lives before and, when they go out of the tavern, they won’t meet again for forty years. And what do they talk about in that momentary halt in the tavern? Of the eternal questions, of the existence of God and immortality. And those who do not believe in God talk of socialism or anarchism, of the transformation of all humanity on a new pattern, so that it all comes to the same, they’re the same questions turned inside out. And masses, masses of the most original Russian boys do nothing but talk of the eternal questions! Isn’t it so?”

That as I’m sure I need not say is from The Brothers Karamazov, so Kaminsky’s interlocutors spoke in an old tradition.

October 9th, 2020 at 1:08 pm

“A man cannot live intensely except at the cost of the self. Now the bourgeois treasures nothing more highly than the self (rudimentary as his may be). And so at the cost of intensity he achieves his own preservation and security. His harvest is a quiet mind which prefers to being possessed by God, as he does comfort to pleasure, convenience to liberty, and a pleasant temperature to that deathly inner consuming fire. The bourgeois is consequently by nature a creature of weak impulses, anxious, fearful of giving himself away and easy to rule.”

Hermann Hesse