“His large, wide face, with its strong planes, forceful jaw, and unforgettable brows, recalled a medieval wood carved saint.”

Nobel poet Czesław Miłosz had a magnificent visage, and it got even better as he aged. I haven’t seen many sculptures that quite capture it, and I don’t think many will – the opportunity died with him in 2004, and it’s not an art that can take place long distance, at least not entirely.

Ironic that the image of the poet who wrote of the struggle against oblivion – with oblivion having the upper hand – has himself disappeared. Or has he? Jonathan E. Hirschfeld has taken on the struggle to keep that visage alive – in clay and word.

The sculptor, who divides his time between Paris and Venice, California, tells the story in Britain’s PN Review: “I have now read about many encounters with Miłosz and many descriptions of his manner. About his remoteness, his warmth, his humour, even his shyness, his impatience, his anger, his resilience, his complexity, his doubts, the force of his words, written when no words were thought possible, his presence. My goal was a synthesis, a kind of summing up, not any one moment, and certainly nothing that one pose could possibly contain.”

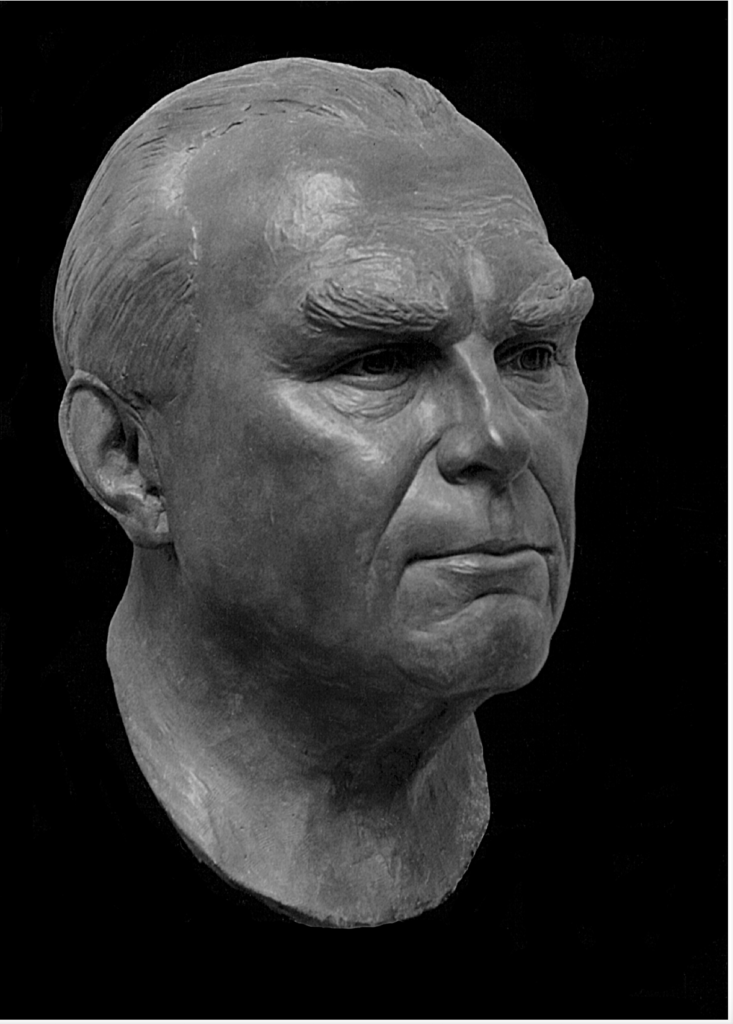

He decided to make the portrait of Miłosz after attending a UCLA reading in 1982. “The room was packed and worshipful,” he recalled. “I recall sensing the paradox of a soft melodious voice that could create a feeling of great closeness while preserving a palpable distance. I knew some of his poetry and a number of his essays and recognised the unmistakable rhythm of his language. Robert Hass, his principle collaborator and translator, has described his ‘fierce, hawkish, standoffish formality’. Even allowing for the animated eyes and mischievous smile, he seemed the incarnation of gravity and dignity. His large, wide face, with its strong planes, forceful jaw, and unforgettable brows, recalled a medieval wood carved saint.”

But would the poet cooperate with the sculptor? He did. Miłosz made time for hours and hours of sittings. And for many photographs, too, to help the sculptor when he was hours away, in southern California or France.

Hirschfeld remembers: “During my time with him I watched as intently as I could, scrutinising every detail, absorbing every shifting mood, reaching for something as unachievable, as metaphysically impossible, as the quest that he himself had defined as the poet’s relationship to reality. However, one must earn one’s discontent. One first must notice the weight of the jaw, the extreme particularity of each feature, the breadth and slope of the forehead, the curl of the lips and the swelling of the planes, the folds around the eyes, the quality of the hair, the telling asymmetries that convey the complexity of the emotions and intellect; one must travel again and again this unique terrain until in the mind’s eye, at night while the clay sleeps, one can feel the entire head as one complex mass, with a structure and a thrust, and tilt belonging to this person alone. When you have done that, you have earned the right to say that something is still missing.”

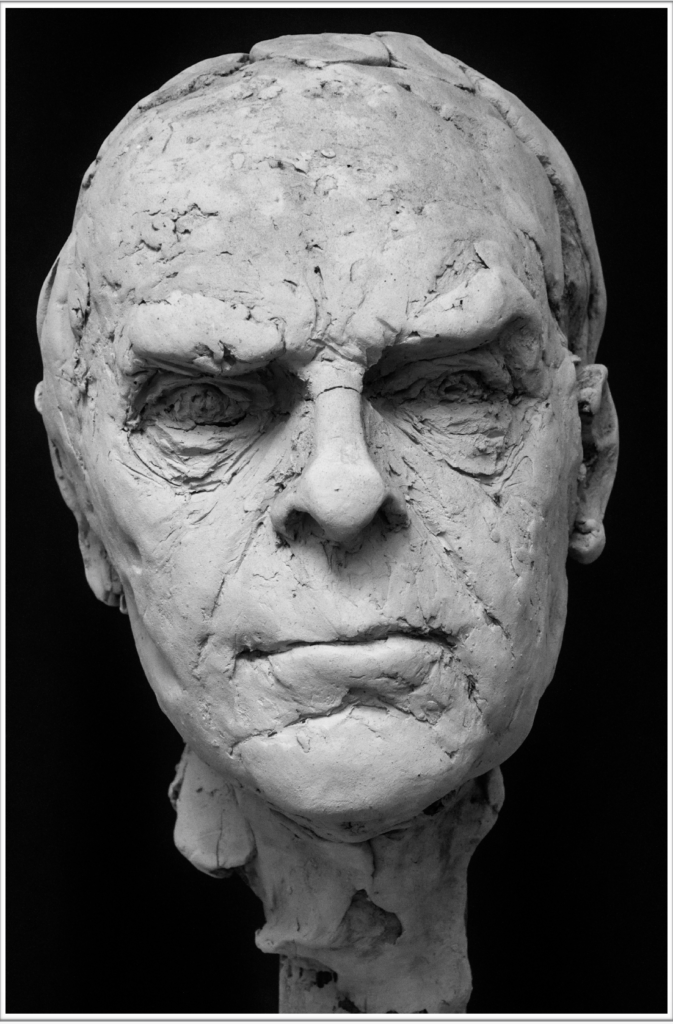

Still, something was still missing. He made the version above in Berkeley, but … he wanted to try again. They continued with a second portrait in Paris.

“The version of Miłosz I made in Paris was more than a sketch, and less than a finished work. It is filled with knotted intensity, rough, unfinished forms and the traces of accident. In ‘Ars Poetica’ (Bells In Winter) Miłosz wrote – ‘The purpose of poetry is to remind us how difficult it is to remain just one person, for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors, and invisible guests come in and out at will.’ – By his own account he was ‘neither noble nor simple’. He had cautioned an interviewer ‘Art is not a sufficient substitute for the problem of leading a moral life. I am afraid of wearing a cloak that is too big for me’ (Czesław Miłosz, 1994, Interviewed by Robert Faggen). I knew there was truth in the dry, raw clay of the second version, and it felt right that it should remain just this way.”

Read the whole thing in the PN Review here. (And stay tuned for some updates on my own forthcoming: Czesław Miłosz: A California Life.)

(Photos copyright Jonathan Hirschfeld.)