Purgatory seems to be on people’s minds this year – we have several new translations of Dante’s canticle to consider in time for Christmas. Fortunately, we have Dantista Robert Pogue Harrison to do the considering for us in the current holiday issue of the New York Review of Books.

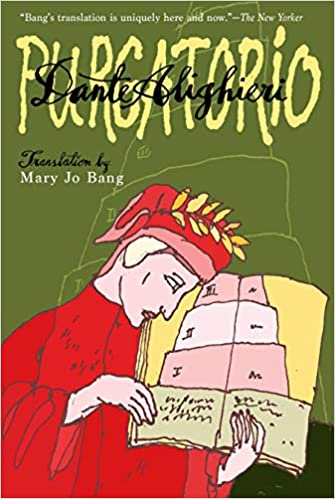

Your choices: a Graywolf Purgatorio translated by poet Mary Jo Bang, another translation by Scottish poet and psychoanalyst D.M. Black (with a preface by Harrison himself – read about it here) from New York Review Books, and finally After Dante: Poets in Purgatory: Translations by Contemporary Poets edited by Nick Havely with Bernard O’Donoghue and published by Arc in Yorkshire. Harrison gives especial attention to a different kind of translation, from words into art: Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno by the late Rachel Owen, edited by David Bowe and published by Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

Why the abundance of translations? “Given Merwin’s excellent version of Purgatorio, plus dozens of others in English, the only reason to undertake yet another translation of it—or any other part of The Divine Comedy, for that matter—is love. ‘Love makes me speak,’ as Dante said…”

Purgatorio is the most approachable of the three canticles of Dante’s Divine Comedy. It has always been my favorite. As Harrison points out, it is the only one of the three in which time matters. And effort matters, too – its inhabitants are all in the struggle to work out their own salvation.

But there’s more. As Harrison writes: “Whereas Hell has no stars, sunsets, or seashores, on Mount Purgatory we are once again under the open sky, where the sun’s movement marks the hours and seasons; where night gives birth to day, and day dies into night; and where the shimmering seas of the southern hemisphere surround the island from all sides.”

“A palpable terraphilia informs the canticle. We find here a love of the planet and everything that makes it our cosmic home—its rivers, valleys, seas, and mountains; its diurnal cycles; its ever-changing light and color; and above all its celestial dome. Not to mention its plant life. After Dante enters the earthly paradise of Eden at the summit of Mount Purgatory, the fair Matelda informs him that he has risen above Earth’s zone of meteorological disturbance. The gentle breeze that graces the ancient forest of Eden comes, she says, from the heavenly spheres as they move from east to west around the planet. This rotational wind scatters seeds from the flora of that primal place to the rest of the planet below: ‘And then the Earth, according to its character/and where it is beneath the heavens, conceives/and by its various powers bears various plants.’ In sum, all the plant life of our burgeoning, self-renewing biosphere has Edenic origins.”

Harrison suggests that Dante had roamed Hell as an insomniac, and that his nightmarish visions were the result of extended sleep deprivation. “

In Purgatory he and Virgil are under strict orders from the angelic guardians of the realm to halt their ascent of the mountain toward evening and, at least in Dante’s case, to sleep at night. On each of the three nights he spends on Mount Purgatory, Dante has vivid dreams, and with each new dawn he wakes up restored.

“Indeed, restoration marks the very purpose of the purgatorial process. While Hell figures as a great gash in the body of Earth, where all the vices that disfigure the soul and human history fester, Purgatory is where the slow, laborious work of healing takes place. Dante, whose pilgrim arrives on the realm’s shores on Easter morning, calls it the soul’s rebeautification (“Creature who cleanse yourself/to go back beautiful to your Creator,” he addresses a penitent in Purgatorio 16). The penitential ordeals of Dante’s Purgatory—many of them as harsh as the punishments in Hell—are intended to restore the prelapsarian probity of human nature and prepare the way for a return to Eden, which Dante locates at the mountain’s summit. Dante himself will enter Eden at the end of his journey through the second realm, and so will all the other penitents after completing their purgation. From that garden of recovered innocence they too, like Dante’s pilgrim, will ascend into heaven.”

Read the whole thing here.

Postscript: Here’s poet and psychoanalyst D.M. Black talking about his translation with NYRB’s Edwin Frank. It’s fascinating.

Tags: D.M. Black, Dante Alighieri, Mary Jo Bang, Rachel Owen, Robert Pogue Harrison

December 10th, 2021 at 6:17 am

[…] more here. […]

December 11th, 2021 at 3:21 pm

During the sale when Schoenhof’s was closing its store in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I received Purgatorio by mistake for something else I had ordered. Schoenhof’s no longer had in stock what I did order, and didn’t want Purgatorio back. So it sits on my shelves, waiting for the day when I shall have learned enough Italian to tackle it.