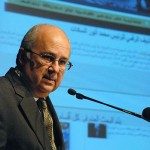

Serageldin (Photo courtesy Sadat Museum)

“The most intelligent man in Egypt.”

That’s the way Stanford librarian Michael Keller introduced Ismail Serageldin, director of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Keller reassured us that he’s not the first to say so.

Photo: Ibrahim Nafie, Courtesy Bibliotheca Alexandrina

Within a few minutes, the audience of about 150 last week at Stanford didn’t need any reassurance: Serageldin began to prove the title. (Keller mentioned that Serageldin had 22 honorary degrees — Serageldin corrected him: as of this week, it’s 26.) It’s hard not to warm to a man who says, like Borges, “I think paradise is some kind of library.”

For those who don’t know, the ancient Library of Alexandria was a legend – certainly the largest and most remarkable in the ancient world. The Ptolemaic center for learning was launched sometime after the death in 323 B.C. of that “megalomaniac young man” who was a student of Aristotle – Alexander the Great. Serageldin emphasizes that it was destroyed in successive stages, finally succumbing sometime after the murder of Hypatia in 415 A.D. and the final Arab sacking in 642 A.D. Then the current revival.

A huge statue of one of its founders, Ptolemy II, was fished out of the Nile, and now presides over the entrance of library, stressing continuity between new and old – but how much continuity is there, really? As Serageldin himself admitted: “The library of the future will not be a replication of the library of the past.”

Photo: Ibrahim Nafie, Courtesy Bibliotheca Alexandrina

Today’s avant-garde library must accommodate “new forms, of knowledge, new forms of storage.”

The plans, in short, are staggering, and my meager attempt to take notes fell behind the pace of the slides, and my ability to believe what I had written. Here’s the easy part: The library already receives 1.2 million visitors and sponsors 700 events annually, including concerts, conferences, book fairs. The website gets 300 million hits a year. A list of some of its goings-ons is here.

Photo: Ibrahim Nafie, Courtesy Bibliotheca Alexandrina

He began to speak of a “world digital library.” He said that, through the library’s technology, no book will ever go out of print. The library will be a venue for eminent intellectuals – already has been, for the likes of Umberto Eco and Nobel laureates. It will sponsor research. It will reissue “the classics of humanistic Islam.”

The goal is “access to all the information, for all people, at all times.” Serageldin showed a dizzying succession of maps, diagrams, charts, bullet points, acronyms and spoke of a “universal networking language.”

The library itself – stunning, modern – reminded me a bit of the sets of alien ships for the television series V.

“Visionary” is a label thrown about too quickly, too easily, perhaps —but for Serageldin, it’s another title that fits. The superlatives rolled over me: Bigger. Fastest. First. Universal. Better – no, best.

Photo: Ibrahim Nafie, Courtesy Bibliotheca Alexandrina

It’s a cliché to note that man’s technological achievements have not been matched by changes in human greed, avarice, and cowardice. But the tables occasionally tip toward spiritual attainment, too. My mind began to turn to another story I was writing, one about a 28-year-old writer who faced death by firing squad, who nevertheless went on, after a Siberian sentence, to write The Brothers Karamazov, Crime and Punishment, and The Idiot.

Both the technical achievements of man’s ingenuity and the ambiguous fruits of human suffering were with me as I left Dinkelspiel Auditorium and stumbled into the unrelenting California sunshine.