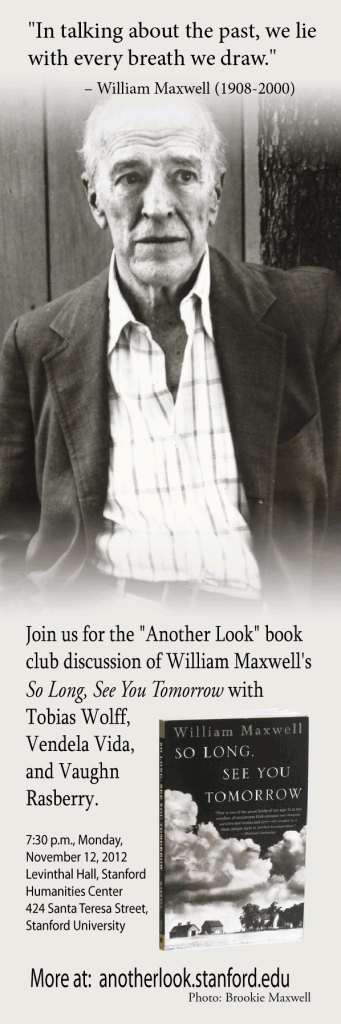

Earlier this week, I announced “Another Look,” Stanford’s book club for the best books you’ve never read. But I didn’t have a chance to give my pitch for William Maxwell‘s masterpiece, So Long, See You Tomorrow. Let me make amends now.

I read the book on the strength of Tobias Wolff‘s powerful recommendation several months ago. The graceful, elegant, and melancholic writing is infused with the Midwestern attitudes and turns of phrase still extant in my own Michigan childhood. As I read, I wondered where those phrases, metaphors, and mindsets have gone since. Maxwell’s excavation of memory has become more urgent with the passage of time. “I didn’t want the things that I loved, and remembered, to go down to oblivion. The only way to avoid that is to write about them,” he said in an interview.

Toby called the book “a beautifully written, complex, haunting story of a boy’s attempt to find warmth and companionship following the death of his mother in the Spanish Influenza epidemic — which killed more people than the Great War it so quickly followed. It is a work of consummate literary artistry, and a cry from the heart that, once heard, cannot be forgotten.”

Toby called the book “a beautifully written, complex, haunting story of a boy’s attempt to find warmth and companionship following the death of his mother in the Spanish Influenza epidemic — which killed more people than the Great War it so quickly followed. It is a work of consummate literary artistry, and a cry from the heart that, once heard, cannot be forgotten.”

When I read the book, I hadn’t yet seen the work Maxwell uses as a metaphor for his childhood, Alberto Giacometti’s “Palace at 4 a.m.,” in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Google found it for me, and when assembling materials for the Another Look website, I thought I would do new readers the favor of including an image of it.

I prefer some of Giocometti’s other work, which is reminiscent of the work of his mentor, the French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. My own father was a sculptor; Bourdelle and Sir Jacob Epstein were perhaps his favorite masters of the medium, and hence became my own. But for Maxwell, Giacometti’s “Palace at 4 a.m.” had a special poignance.

Here’s his ekphrastic turn in So Long, See You Tomorrow. I liked the last line so much, I used it in our bookmark for the event – you can pick up one of the bookmarks at the Stanford Bookstore, or at the Stanford Libraries – or drop me a line and I’ll save one for you.

From Maxwell:

“When, wandering around through the Museum of Modern Art, I come upon the piece of sculpture by Alberto Giacometti with the title ‘Palace at 4 a.m.,’ I always stand back and look at it – partly because it reminds me of my father’s new house in its unfinished state and partly because it is so beautiful. It is about thirty inches high and sufficiently well known that I probably don’t need to describe it. But anyway, it is made of wood, and there are no solid walls, only thin uprights and horizontal beams. There is the suggestion of a classic pediment and of a tower. Flying around in a room at the top of the palace there is a queer-looking creature with the head of a monkey wrench. A bird? a cross between a male ballet dancer and a pterodactyl? Below it, in a kind of freestanding closet, the backbone of some animal. To the left, backed by three off-white parallelograms, what could be an imposing female figure or one of the more important pieces of a chess set. And, in about the position a basketball ring would occupy, a vertical, hollowed-out spatulate shape with a ball in front of it. …

“I seem to remember that I went to the new house one winter day and saw snow descending through the attic to the upstairs bedrooms. It could also be that I never did any such thing, for I am fairly certain that in a snapshot album I have lost track of there was a picture of the house taken in the circumstances I have just described, and it is possible that I am remembering that rather than an actual experience. What we, or at any rate what I, refer to confidently as memory – meaning a moment, a scene, a fact that has been subjected to a fixative and thereby rescued from oblivion – is really a form of storytelling that goes on continually in the mind and often changes with the telling. Too many conflicting emotional interests are involved for life ever to be wholly acceptable, and possibly it is the work of the storyteller to rearrange things so that they conform to this end. In any case, in talking about the past we lie with every breath we draw.”

Tags: Alberto Giacometti, Antoine Bourdelle, Sir Jacob Epstein, Tobias Wolff, William Maxwell

September 8th, 2015 at 11:08 am

I thought this book quite wonderful. In some ways it’s a bit like a detective story told backwards. One is told of the crime of murder but at the same time is the other troubling problem, veiled but pervasive, of not empathising with the son of the murderer. Just the line about not knowing how it was to be inside that boy when his father was being pursued by blood hounds. The real”crime” committed by the writer is passing by that boy years later instead of acknowledging him. Shakespeare’s words about a “frail bark” come to mind as one is made aware of the whole human edifice of emotional and recalled events and the so poingant words about the lies we tell ourselves whenever we try to retell the past.

The quite amazing evocation of grief. The understanding that it casts a shadow ahead of us for the rest of our lives, is constantly breathed through the book but never stated so crudely. Yet this book is not gloomy or depressing, so why is that? Is it because we meet a mind so full of kind understanding, and putting forth the complexity of the human heart without any judgements?

September 8th, 2015 at 11:12 am

Thanks, Mary. Lovely observations. You might want to check out our podcast of this event. A couple of the panelists wondered whether the boyhood friend exists at all!