The big day arrived. Scotland voted on a referendum deciding whether to declare independence from the United Kingdom or stick together. My own thoughts turned to Stanford’s Scotland expert, and I wondered how he might be faring. We’ve written about Bliss Carnochan and his book Scotland the Brave here and here. We dropped him a sympathetic line to ask for his thoughts on this momentous occasion.

He replied within an hour or so, long before the votes were tallied and much faster than I was expecting:

“On the front page of the Financial Times today is a very large headline and, below, an image of the Scottish flag, the Saltire, against a background of clouds and atmospheric effects. The headline: BEAUTY AND TERROR GRIP A NATION POISED ON THE BRINK OF HISTORY.

“The acres of coverage produced by the independence vote have been astonishing, as if the fate of the world depended on this decision by a small nation, five million people only. The question of Quebec’s independence produced nothing like this. No doubt more is at stake here, political, economic, otherwise. But I think Scottish identity-fever, shared by many who have little or no Scottish blood, adds its share to the apocalyptic vision of beauty and terror. We’re all Scottish now, anxious about our true identity.

“In Scotland the Brave, I wondered whether a yes vote might diminish the creativity (and the enmity to England) of so much Scottish thought – a perverse reason to vote no, which I’d probably do if I had a vote. Having voted no, then I’d probably wish I could have a second chance. Being a Scot, even five generations back, leaves me of divided mind. It’s what Hugh MacDiarmid called the “Caledonian antisyzygy.”

According to Wikipedia, “The term Caledonian Antisyzygy refers to the ‘idea of dueling polarities within one entity’, thought of as typical for the Scottish psyche and literature. It was first coined by G. Gregory Smith in his 1919 book Scottish Literature: Character and Influence …” Read MacDiarmid’s poetic take on it is here.

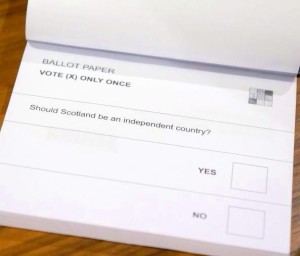

Now here’s the hard part to figure out. The ballot is pictured below left. It’s said to be the simplest ballot evah. So how did Scotland wind up with 3,261 rejected ballots, which were indecipherable? What’s to screw up?

As the votes were counted well into the night, and the nays were in the lead, Bliss emailed me again: “Good: the bad guys have it. Oh dear: the good guys lost. Looks like it will be Scotland v. England forever. But can somebody explain why Shetland, Orkney & the Western Isles all said no??”

As for me, I poured a wee draught of Laphroaig to toast the Scots as we rolled past midnight, and were still awaiting the vote from the Highlands. Laphraoig’s own isle of Islay in the Argyll and Bute region had voted “no” by 58.52%. I had to agree with Paul Krugman and the other nay-sayers about the economic and political catastrophe that was likely to ensue had the referendum passed. Had the “yes” vote won, I would have had to head down to the nearest BevMo to stockpile Laphroaig while the price was still within reason, to make sure I had the comfort of Scottish peat within the confines of my home, come what may in the world at large.