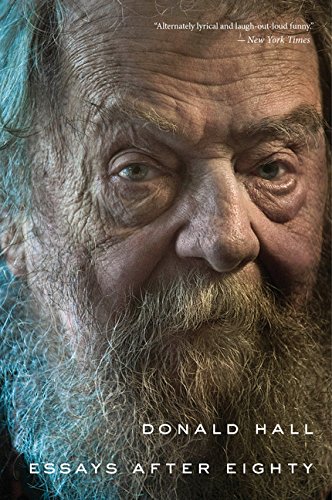

Not funny. Donald Hall receiving the National Medal of Arts, 2011.

Update on June 24, 2018: Donald Hall died last night. Some memories from Don Share, editor of Poetry Magazine:

“It was only a few weeks ago that I last was in touch with Don Hall. He was so pleased with Martín Espada’s being awarded the Lilly Prize; and he always mentioned – of course! – baseball, family life, and poetry: “I wish I still wrote poems” was the last thing he wrote to me, alongside his praise of the direction POETRY, which he read faithfully, has been taking. His kindness and generosity was spontaneous, unbidden, and abiding, and these things were watered from the same deep well as his poetry. He was capacious, more so than he got credit for being. And literally to the end, he was gently courageous and somehow funny, too. He wanted to remember, perhaps, more than be remembered; but lots of us will think about him and his life in poetry all our days.”

He was one of those rare creatures, a poet who writes into advanced age and illuminates the path for the rest of us. My earlier post from 2016, on Donald Hall and old age.

The endless ageism of this election cycle has been a dispiriting spectacle for quite some time. In fact, you are welcome to join me in documenting it on my Twitter hashtag #Ageism2016. While we live in a society that is fascinated with attractiveness and youth in its leaders (cough, cough, Justin Trudeau), it stands to reason that anyone with sagacity and experience for international leadership will have cycled more than a few dozen times around the sun. But politics is not the only arena where wisdom comes with years.

Remember way back when we targeted The Washington Post‘s casual (and, I suspect, unintended) dissing of poet Donald Hall when he received the National Medal of Arts in 2011? The diss involved a caption contest for a “funny” photo of the poet. We created something of a national stir with that one, with even Sarah Palin chiming in – you can read about it here and here.

I hadn’t read the 87-year-old poet’s latest collection of essays Essays After Eighty, but Maria Popova over at Brain Pickings had, and apparently a caption contest was the least of the insults he had to work with that day in Washington, D.C. From one of Hall’s essays:

“I go to Washington to receive the National Medal of Arts and arrive two days early to look at paintings. At the National Gallery of Art, Linda [Hall’s girlfriend] pushes me in a wheelchair from painting to painting. We stop by a Henry Moore carving. A museum guard, a man in his sixties with a small pepper-and-salt mustache, approaches us and helpfully tells us the name of the sculptor. I wrote a book about Moore and knew him well. Linda and I separately think of mentioning my connection but instantly suppress the notion — egotistic, and maybe embarrassing to the guard. A couple of hours later, we emerge from the cafeteria and see the same man, who asks Linda if she enjoyed her lunch. Then he bends over to address me, wags his finger, smiles a grotesque smile, and raises his voice to ask, ‘Did we have a nice din-din?’”

His forbearance is greater than mine would have been. There’s a reason little old ladies carry handbags (hint: remember Ruth Buzzi.) But the indignities of age didn’t end with the guard or the caption contest. At the ceremony, President Obama bent to whisper a few memorable sentences in his left ear. Except that Hall is completely deaf in his left ear, and never heard them.

Relief was near at hand:

Relief was near at hand:

On the day of the medal, [Linda] wheeled me from the Willard InterContinental Hotel to the White House. Waiting at the entrance to go through security, I looked up to see Philip Roth, whom I recognized from long ago. I loved his novels. He saw me in the hotel’s wheelchair — my enormous beard and erupting hair, my body wracked with antiquity — and said, “I haven’t seen you for fifty years!” How did he remember me? We had met in George Plimpton’s living room in the 1950s. I praised what he wrote about George in Exit Ghost. [I wrote about the passage in Exit Ghost here – C.H.] He seemed pleased, and glanced down at me in the chair. “How are you doing?” I told him fine, “I’m still writing.”

He said, “What else is there?”

It’s litotes to point out that none of us are getting any younger, but as I travel this dark road myself, I find the journey more interesting than anyone had ever told me it would be. Donald Hall apparently feels the same way. He holds a lamp for us as we all move forward into the night, with his wry self-awareness, stoic anguish, and endless insight:

“After a life of loving the old, by natural law I turned old myself. Decades followed each other — thirty was terrifying, forty I never noticed because I was drunk, fifty was best with a total change of life, sixty began to extend the bliss of fifty — and then came my cancers, Jane’s death [i.e, his wife, the poet Jane Kenyon], and over the years I traveled to another universe. However alert we are, however much we think we know what will happen, antiquity remains an unknown, unanticipated galaxy. It is alien, and old people are a separate form of life. They have green skin, with two heads that sprout antennae. They can be pleasant, they can be annoying — in the supermarket, these old ladies won’t get out of my way — but most important they are permanently other. When we turn eighty, we understand that we are extraterrestrial. If we forget for a moment that we are old, we are reminded when we try to stand up, or when we encounter someone young, who appears to observe green skin, extra heads, and protuberances.

People’s response to our separateness can be callous, can be goodhearted, and is always condescending… At a family dinner, my children and grandchildren pay fond attention to me; I may be peripheral, but I am not invisible. A grandchild’s college roommate, encountered for the first time, pulls a chair to sit with her back directly in front of me, cutting me off from the family circle: I don’t exist.

When kindness to the old is condescending, it is aware of itself as benignity while it asserts its power. Sometimes the reaction to antiquity becomes farce.

Tags: Donald Hall, George Plimpton, Philip Roth

April 17th, 2016 at 7:11 pm

The interaction with Roth is priceless. It’s comforting to remember that even in the next, unanticipated galaxy, you might encounter an old friend.

April 17th, 2016 at 7:12 pm

Indeed!

April 17th, 2016 at 9:21 pm

This is a beautiful and difficult post, Cynthia.

When I was in my early thirties, I looked after my Hungarian grandmother during the last week of her life. She spoke bluntly about being ready to die, but one chirpy teenaged cousin (a mutant who somehow didn’t get the Eastern European dwell-on-your-own-mortality gene) made a point of telling her, repeatedly, that she’d be up and moving about again in no time. Condescension toward the elderly is thoughtless, but I learned that it’s even worse when it’s rooted in dishonesty.