“You all know me — but I don’t know you!” she almost squealed. She might have won over the crowd in that moment on Tuesday night, had she not already held them in the palm of her hand. Hard, in that instant, to see her as a fierce, unflagging critic of radical Islam and the target of a fatwa.

“You all know me — but I don’t know you!” she almost squealed. She might have won over the crowd in that moment on Tuesday night, had she not already held them in the palm of her hand. Hard, in that instant, to see her as a fierce, unflagging critic of radical Islam and the target of a fatwa.

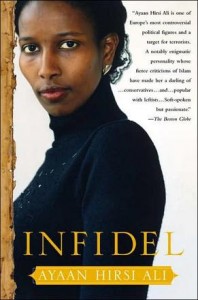

The Palo Alto audience had just been asked how many had read Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s book, Infidel. Almost all the hands in the sold-out Cubberley Community Theatre shot up instantly.

I kept mine down. Two weeks ago I had posted the Guardian profile of the author on my Facebook page; I’d only heard the name a few times before. The joy of blog reporting: suddenly I found myself sitting within 15 feet of her.

“I love San Francisco! I love the food, I love the people!” she cooed appealingly.

Let’s face it, it helps to be beautiful (Timothy Garton Ash was trashed for saying so), as well as incorrigibly likable: The willowy Somalian with the unforgettable face was wearing a fashionable gray sweater and black slacks with trendy wedge-heeled sandals. And Garton Ash was right to a point: beauty and appeal distorts our consideration of a woman who, in this case, needs to be taken very seriously on her own terms.

“I wanted to write papers full of footnotes and statistics. Nobody was interested,” she recalled. People wanted to know instead how she made the break from her past; they wanted to know, in particular, about the family she described in Infidel. How is her mother? “I don’t know. She’s in Kenya. Get lost!”… “I’d say shut up about my mother. I’ve just written a paper!”

“They’re interested in experiences. Most people in the United States and Europe have not had those experiences.” So she shared her story instead.

And wow, what a backstory: She survived genital mutilation, escaped an arranged marriage with a much-older man, became an MP in Holland, and collaborated with Theo van Gogh on his film, Submission, about the treatment of women in Islam. Since his assassination (a letter addressed to her was pinned to his chest when he was stabbed), she has been accompanied by bodyguards to protect her from a fatwa. She is the author of a New York Times bestseller, with a second memoir just published. She has been championed by Paul Berman; she has debated Timothy Garton Ash.

And wow, what a backstory: She survived genital mutilation, escaped an arranged marriage with a much-older man, became an MP in Holland, and collaborated with Theo van Gogh on his film, Submission, about the treatment of women in Islam. Since his assassination (a letter addressed to her was pinned to his chest when he was stabbed), she has been accompanied by bodyguards to protect her from a fatwa. She is the author of a New York Times bestseller, with a second memoir just published. She has been championed by Paul Berman; she has debated Timothy Garton Ash.

When her moderator, Susanne Pari, author of 1997’s The Fortune Catcher, soft-balled her a question about “the patriarchy,” Hirsi Ali balked. “I don’t know if you can call it a patriarchy,” she said, since the women “not only participate in it, but impose it.” Her grandmother had insisted on Hirsi Ali’s genital mutilation; in honor killings and punishments, “the first stage is a sister, mother, mother-in-law. ‘She dropped her headscarf,’ ‘She’s wearing makeup,’ ‘She’s seeing so-and-so.'”

Boys are victimized, too: they are taught that “the male individual is not to be soft but be hard … his honor is between my legs.”

When asked about recent U.S. compromises on female mutilation, Hirsi Ali refused to take the bait, preferring to go to root causes: “It all comes back to honor” and “the conviction that the girl has to be a virgin on her wedding night.”

She decried the Western focus on “poverty, poverty, poverty — let’s get rid of the poverty.” Poverty, she said, “is only the outcome of these convictions.”

“It lets men off the hook.” She favors a paradigm shift in the culture, allowing women to “own their sexuality,” and encouraging men to “want a fellow human being in a relationship.”

Pari brought up the case of Faisal Shahzad, an apparently assimilated Muslim who turned to jihad with the attempted Times Square bombing — but Hirsi interrupted her comments about the possible cause being his job loss.

Pari brought up the case of Faisal Shahzad, an apparently assimilated Muslim who turned to jihad with the attempted Times Square bombing — but Hirsi interrupted her comments about the possible cause being his job loss.

“I have a problem with that,” she said. If we even “remotely entertain” the notion that “foreclosure and health care and normal adversity is an excuse to take away the life of another,” then “we are really going down,” she said.

“He has a freaking MBA!” she exploded. “I know people who can’t read!” Hirsi Ali denied that “the only therapy is to get an SUV and fill it with explosives.” Nor did she excuse Nidal Malik Hasan, who “gets to be a major in a voluntary army.”

“Why don’t we take these people at their word? Why don’t we examine their convictions?”

Pari noted that, in her Iran-American childhood, there was only one mosque in the nation, in Washington D.C., and now there are thousands (“1150,” corrected Hirsi Ali). She took Hirsi Ali, a fellow atheist, to task for Infidel’s conclusion that the love and tolerance exhibited in much of Christianity might be a force to subdue Islam. “I was very naughty!” Hirsi Ali admitted with a chuckle.

Pari said the author’s idea “was disturbing to me, frankly…What were you thinking?”

“The superficial answer is, if every Muslim became Christian, I would live without bodyguards,” Hirsi Ali replied.

“This is a really hard interview,” admitted Pari.

I, for one, would have liked a paper as much as the stories, if not more. As a mother (and a daughter) reading some of the tales, I saw enough stock issues of parent-child estrangement in the book to wonder how much was culture clash and how much was the intergenerational conflict that takes place everywhere.

Leafing through her newest book, Nomad, I liked as much the bits of the book that were blistering polemic against misogyny – in short, a paper. She exhorts wet-noodle Western feminists who “manifest an almost neurotic fear of offending a minority group’s culture,” where a dread of offending overcomes compassion and justice:

There are 13.5 million women in Saudi Arabia. Imagine what it’s like to be a woman there: you are essentially under permanent house arrest.

There are 34 million women in Iran. Imagine being a woman there: you may be married legally when you are nine; on the order of a judge, you may be lashed 99 times with a whip for committing adultery; then, on the order of a second judge, you may be sentenced five months later to death by stoning. This is what happened to Zoreh and Azar Kabiri-niat in Shahryar, Iran, in 2007; after being flogged for “illicit relations” they were then tried again and found guilty of “committing adultery while married.” The punishment they were to receive for adultery was death by stoning. Their sentence was recently confirmed, on appeal.

There are 82.5 million women in Pakistan. Imagine being a girl there: you grow up knowing that if you dishonor your family, if you refuse to marry the man chosen for you, or if someone thinks you have a boyfriend, you are likely to be beaten, ostracized, and killed, probably by your father or brother, who has the support of your entire immediate family. You’re also liable to be jailed …

Virginity is the obsession, the neurosis, of Islam.

As I began to feel my own reservations during the conversation, I continued to hear the audience groan, moan, and applaud their approval. It was love fest. The crowd was one.

It was, in short, a friendly mob. I was grateful for my moments of alienation; they kept me from falling into the crowd emotion. As Auden wrote:

Few people accept each other and most

will never do anything properly,but the crowd rejects no one, joining the crowd

is the only thing all men can do.Only because of that can we say

all men are our brothers …

I wonder if Hirsi Ali will keep her intellectual independence, or whether her nonconformity is in part a byproduct of repeated dislocation. Many forces are trying to coopt or own her. In her writing, she longs for acceptance and a place of belonging after so much rejection. Will applause wear away this brilliant woman’s provocative edginesss?

Pari opens last Sunday’s San Francisco Chronicle review of Hirsi Ali’s new book with: “For the very few of us who have chosen atheism over Islam, the world is a dangerous place. Radical clerics call for our death and encourage our murder. It is the time of our Inquisition, and the urgent issue is how to extinguish these threats so that we, and others, may safely believe what we wish.”

But after listening to Ayaan, I’m not sure how much this is Pari’s opinion, and how much the author’s.

They both seemed to endorse religion to the extent that people don’t believe or practice it. But religions and beliefs have always evoked the most passionate side of man’s nature and engagement – and so has as much chance of turning man into a devil as an angel. As another Enlightenment, or perhaps slightly pre-Enlightenment figure, Blaise Pascal, wrote: L’homme n’est ni ange ni bête, et le malheur veut que qui veut faire l’ange fait la bête.

Perhaps the volatility, the unpredictability, of man’s passionate possibilities helped drive both women to the blinkered god of rationality. They embraced instead what Hirsi Ali terms “Enlightenment” values – ah, but the Enlightenment had a few passions of its own. A good reading of the excesses of the Revolution should cure whatever nostalgia anyone has for the Enlightenment, and for what happens to man when he imagines he is relying on nothing but his or her own sweet reason.

There are other cures as well. Christopher Hitchens is coming to town next month…

Tags: Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Paul Berman

May 27th, 2010 at 10:05 am

Interesting you should note that “Many forces are trying to coopt or own her.”

May 27th, 2010 at 10:16 am

Edginess can very quickly become shtick. Market forces will push her to that — to the next edgy book, for example. Right now she has no permanent alliances and fealties, and it’s relatively easy to resist the political causes and clubs that will want to promote her for their own agenda. Her evident joy at the warm reception she received might be a warning signal — it can very quickly flip into a stick of withheld approval that, at a future point, can be used to shape her opinions. She is in a new world, and despite her steely prose, she seems very vulnerable and open.

May 27th, 2010 at 1:15 pm

It would be heartbreaking for such a beautiful and brave woman to be commodified in the US after resisting the tribal version of that dynamic.

May 27th, 2010 at 1:55 pm

Well, to some extent she already has been packaged. Just depends on whether she can figure things out and get to the control room fast enough. She’s a provocative and unpredictable voice to add to the American mix — but in the great republic, everything conduces towards blandness, and things that stick up tend to be hammered down in pretty short order.

Her book suggests that she has idealized America, but there are some big rocks under the surface, and it’s not clear whether she sees them. Not to mention a fatwa ON the surface.

But I don’t mean to make her sound like a marketing phenomenon. Obviously she is not. And that brings us back to the note that was pinned on the corpse of Theo van Gogh. The more disturbing Western trend is to marginalize her and dismiss her. Why? Because she is a woman? Because what she is saying is politically incorrect, not to mention dangerous? Because she is giving a witness that may make us have to get up off our asses on a few uncomfortable issues? It’s becoming a familiar saw when talking about her to recall how the literati formed a phalanx around Salman Rushdie in 1989.

Where is the support for her and other dissenters from these societies? Or our own cartoonists, for that matter? The slow move away from taking a principled stance is beginning to remind me of Dürrenmatt’s “The Visit.”

May 28th, 2010 at 10:50 pm

Although it is from last year, I think you may find this book review useful. The author comes from a Muslim perspective and reviews her works. The link is here … it is good to hear other opinions and ideas.

http://loga-abdullah.blogspot.com/2008/11/defending-our-diin-ayaan-hirsi-ali.html

Hope you find it interesting.

May 31st, 2010 at 4:21 pm

Like you, I disagree with much of what Ms. Hirsi Ali says. I defend, however, her right to say it, as I’m sure you do as well. Real freedom of speech begins with the freedom to offend — otherwise it means nothing.

I fully support her denunciation of “honor” killings, stoning women to death, child marriages, and other forms of abuse and violence, whether here or elsewhere in the world.

I think the big point is that this is a woman who has committed no violence, and has advocated no violence — yet she is part of a growing number of people (including Salman Rushdie) who must living in hiding, and have bodyguards 24/7 for the rest of their lives.

As you say, “it is good to hear other opinions and ideas.” And certainly I welcome those who would urge a more judicious weighing of her more extreme statements, as many do.

Thank you for posting!