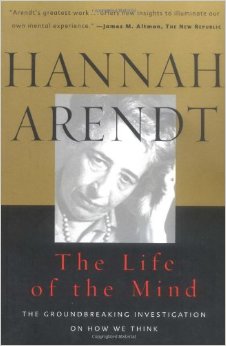

Immigration is much in the news, and will be for some time to come. Hence, philosopher Hannah Arendt‘s important and apparently little-known 1943 essay, “We Refugees” is very timely. The Book Haven has occasionally posted about one of the last century’s most famous immigrants: Arendt left Germany for Czechoslovakia and then Geneva and then France, where she was placed in an internment camp. She finally made a home in the U.S. in 1941. Although, of course, she was writing with the Jews and the Holocaust in mind, the reader may substitute the term “Islamic refugees” or “Christian minorities in the Middle East” for up-to-date applications. Her conclusion is all the more stunning for that reason. The piece in its entirety is too good for excerpting, really – you can read the whole thing here – but I’ll do my best:

“A new kind of human beings…”

Our optimism, indeed, is admirable, even if we say so ourselves. The story of our struggle has finally become known. We lost our home, which means the familiarity of daily life. We lost our occupation, which means the confidence that we are of some use in this world. We lost our language, which means the naturalness of reactions, the simplicity of gestures, the unaffected expression of feelings. We left our relatives in the Polish ghettos and our best friends have been killed in concentration camps, and that means the rupture of our private lives.

Nevertheless, as soon as we were saved – and most of us had to be saved several times – we started our new lives and tried to follow as closely as possible all the good advice our saviors passed on to us. We were told to forget; and we forgot quicker than anybody ever could imagine. In a friendly way we were reminded that the new country would become a new home; and after four weeks in France or six weeks in America, we pretended to be Frenchmen or Americans. The more optimistic among us would even add that their whole former life had been passed in a kind of unconscious exile and only their new country now taught them what a home really looks like. …

In order to forget more efficiently we rather avoid any allusion to concentration or internment camps we experienced in nearly all European countries – it might be interpreted as pessimism or lack of confidence in the new homeland. Besides, how often have we been told that nobody likes to listen to all that; hell is no longer a religious belief or a fantasy, but something as real as houses and stones and trees. Apparently nobody wants to know that contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings – the kind that are put in concentration camps by their foes and internment camps by their friends. …

I don’t know which memories and which thoughts nightly dwell in our dreams. I dare not ask for information, since I, too, had rather be an optimist. But sometimes I imagine that at least nightly we think of our dead or we remember the poems we once loved. I could even understand how our friends of the West coast, during the curfew, should have had such curious notions as to believe that we are not only ‘prospective citizens’ but present ‘enemy aliens.’ In daylight, of course, we become only ‘technically’ enemy aliens – all refugees know this. But when technical reasons prevented you from leaving your home during the dark hours, it certainly was not easy to avoid some dark speculations about the relation between technicality and reality.

No, there is something wrong with our optimism. There are those odd optimists among us who, having made a lot of optimistic speeches, go home and turn on the gas or make use of a skyscraper in quite an unexpected way. They seem to prove that our proclaimed cheerfulness is based on a dangerous readiness for death. … Instead of fighting – or thinking about how to become able to fight back – refugees have got used to wishing death to friends or relatives; if somebody dies, we cheerfully imagine all the trouble he has been saved. Finally many of us end by wishing that we, too, could be saved some trouble, and act accordingly.

No, there is something wrong with our optimism. There are those odd optimists among us who, having made a lot of optimistic speeches, go home and turn on the gas or make use of a skyscraper in quite an unexpected way. They seem to prove that our proclaimed cheerfulness is based on a dangerous readiness for death. … Instead of fighting – or thinking about how to become able to fight back – refugees have got used to wishing death to friends or relatives; if somebody dies, we cheerfully imagine all the trouble he has been saved. Finally many of us end by wishing that we, too, could be saved some trouble, and act accordingly.

She concludes that, for the Jews:

…history is no longer a closed book to them and politics is no longer the privilege of the Gentiles. They know the outlawing of the Jewish people in Europe has been followed closely by the outlawing of most European nations. Refugees driven from country to country represent the vanguard of their peoples – if they keep their identity. For the first time Jewish history is not separate but tied up with that of all other nations. The comity of European peoples went to pieces when, and because, it allowed its weakest member to be excluded and persecuted.

Again, read the whole thing here.

Tags: "Hannah Arendt"

September 12th, 2016 at 11:31 pm

Thanks for making your readers aware of this essay, Cynthia. I’m struck by the deliberate density of Arendt’s prose—how she forces us to slow down and work through her implications, wind through a labyrinth of moral considerations with no clear exit, pause before her small notes of rueful humor. This essay is relevant in ways that our current dumb media narratives and sociopolitical arguments too easily obscure.