September 1, 1939, is the day Nazi Germany invaded Poland. W.H. Auden famously wrote a poem to commemorate the occasion. “September 1, 1939” begins:

September 1, 1939, is the day Nazi Germany invaded Poland. W.H. Auden famously wrote a poem to commemorate the occasion. “September 1, 1939” begins:

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

The poem was taken up after 9/11, and appeared under thumb tacks and refrigerator magnets throughout the nation. But the last lines of the second stanza got special scrutiny in the new century. Was it referring to eternal truths? Or claiming the Versailles Treaty that ended World War I justified the new invasion? Writing in the New York Times, Peter Steinfels asked: “One suspects that these characterizations would earn sharp rebukes if expressed in a poem titled ”September 11, 2001.’ More important, would a contemporary version of the 1939 poem be found guilty of what has come to be labeled ”moral equivalence’? Was Auden shifting moral responsibility from totalitarian evildoers to past misdeeds by those under attack and to a universal human egotism in which everyone was more or less equally complicit?”

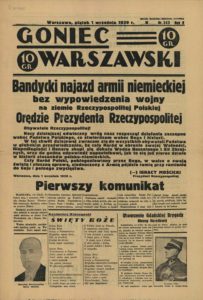

Headline: “Bandit invasion of the German army without declaring war on the lands of the Republic of Poland”

I would argue that to state a human principle, based on observation, is not to say that it is justifiable, admirable, or advisable. It is simply to say that it happens. Look at the Middle East. Look at the reprisals and mutual blame among factions in our national politics. Or between Putin and Trump. Or everyone in the world and North Korea. Tit for tat is a universal principle. But can it be reversed? Even on a small scale in our political sphere, will kindness cause a reciprocation of kindness? Can turning the other cheek become contagious? Unlikely. It takes forethought, intention, and forbearance. Retaliation requires only impulse.

A number of posts on Facebook to commemorate the occasion and the poem. From the poet and friend Alfred Corn: “One of the building blocks of Auden’s poem is the idea that ‘The buck stops here.’ Those to whom evil is done 99.9% of the time do evil in return. But a better choice is to repay evil with good. To break the cycle of vengeance rather than perpetuate it. A radical proposal, departing from all natural and normal responses. And yet on those occasions when it has been adopted, the results were redemptive. Not easy. Takes practice. Worth it.”

The penaultimate stanza of the poem:

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

There’s the rub: Auden withdrew the poem from several collections because the last line struck him as glib. We don’t die for failure to love, do we? But there are so many ways to die, and so many ways to live, and six years after the poem was written, a couple big bombs over Japan convinced many of us we must live or die as a species.

In an essay, “The Normal Heart Condition According to Auden,” included in We must love one another or die : the life and legacies of Larry Kramer, Alfred Corn wrote:

Alfred Corn: an optimist?

If this poem engaged Larry Kramer so much that he chose to title two of his dramatic works with phrases drawn from it, we can also note that he is not alone in his admiration. It is one of the few Auden poems that ‘the common reader’ (that endangered species) can be counted on to recognize, and its apologists include Joseph Brodsky, who has written persuasively about its meaning and importance. The famous line from stanza eight, ‘We must love one another or die,’ has become proverbial, often quoted by people who have no idea where it comes from. A strange irony is that Auden himself, within a few years after the poem’s composition, came to dislike it. In his first Collected Poems, published in 1944, he reprinted ‘September 1, 1939’ minus the eighth stanza, which must have disappointed readers who were looking for what they regarded as its profoundest line. In later collections of his poetry, Auden dropped the whole poem and always refused permission for its inclusion in new anthologies; it was not reprinted until after his death, in the volume noted above. Auden decided that the famous line about love and death was untruthful; he remarked, in public and in private, that we are all destined to die, whether or not we love each other.

It takes only a moment’s reflection to recognize this as a misinterpretation of the line’s actual meaning. In a poem whose point of departure is the date on which Nazi Germany invaded Poland and set into motion the Second World War, we are clearly meant to understand that the opposite of love is killing; that, if we fail to love, inevitably we’ll perform acts of violence. Auden could have revised the line and made its real meaning more explicit by saying, ‘We must either love or kill each other,’ but that revision wouldn’t fit the iambic trimeter in which the poem was written, nor would it rhyme with any other line in the stanza. No doubt Auden could have found some other workable solution, but he didn’t attempt to do so (apart from simply excising the stanza in its first reprinting).”

You can read the whole poem here.

Tags: Alfred Corn, W.H. Auden

September 4th, 2017 at 3:38 am

‘Flo Whittaker had once gently reproved Dr. Rosenbaum for his attitude toward politics. She had done so by quoting to him, in tones that rather made for righteousness, a line of poetry that she had often seen quoted in this connection: “We must love one another or die.” Dr. Rosenbaum replied: “We must love one another and die.”‘

Randall Jarrell, Pictures from an Institution (early 1950s)