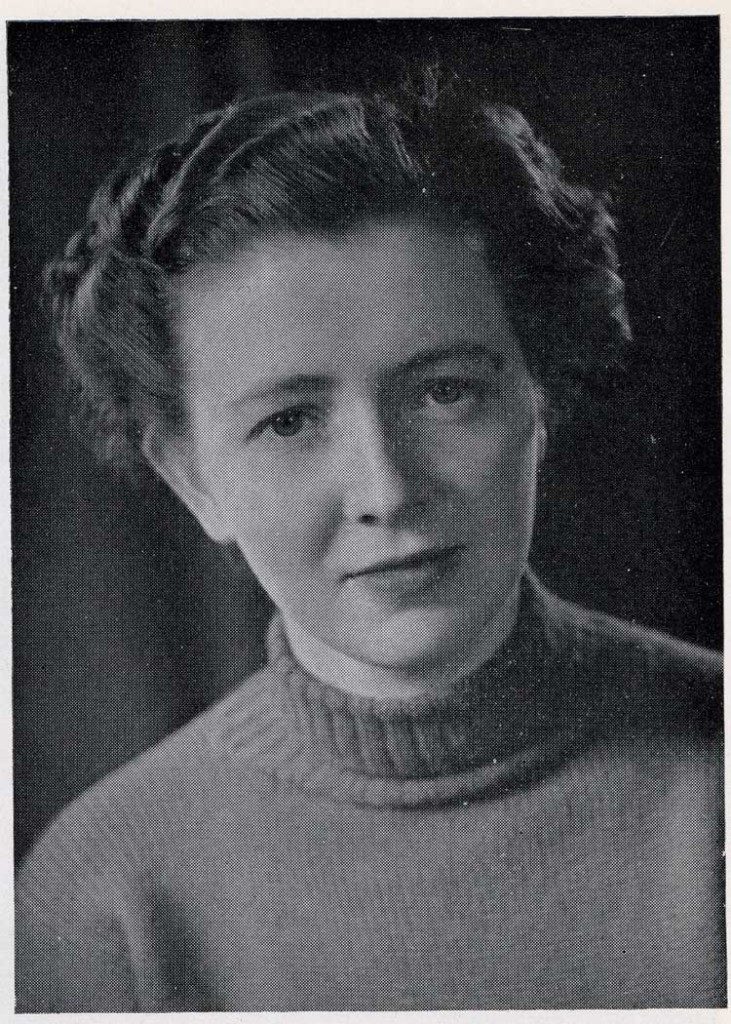

Elizabeth Jennings – rediscovered.

Dana Gioia has a superb essay over in First Things, “Clarify me, please, God of the galaxies,” about Elizabeth Jennings, the only woman in the “Movement” poets of the U.K. (We’ve regularly written about a few of the others – Philip Larkin, Robert Conquest, Thom Gunn.) She echoes the Movement credo, with a soupçon of Christian mysticism perhaps, when she writes: “Only one thing must be cast out, and that is the vague. Only true clarity reaches to the heights and the depths of human, and more than human, understanding.”

Never heard of her? “Although mocked by the press and neglected by scholars, Jennings enjoyed a popular readership in the U.K.,” Dana writes. “Her Selected Poems (1979) sold more than 50,000 copies. Her poems became A-level texts for secondary schools. Her steadfast publisher, Michael Schmidt of Carcanet, claims she became his bestselling author—’the most unconditionally loved’ poet of her generation.”

She lived her life almost entirely in Oxfordshire, where she experienced mental breakdown and subsequent hospitalization, under-employment and unemployment, and shabby poverty, but nevertheless earned many awards and much recognition. When she received the Commander of the Order of the British Empire (C.B.E) at Buckingham Palace in 1992, the press criticized her for looking like a “bag lady.” She died in 2001, at 75.

“Jennings was not a great poet. Greatness had no appeal to her. She admired epic visionaries, such as Dante, Milton, and Eliot, who offered sublime visions of civilization and belief. She recognized, however, that her muse was lyric. Jennings’s ‘great’ subject was how the individual—fragile, isolated, but alert—worked her way through life’s difficulties and wonders. Her sensibility was romantic, but her style was neoclassical. The characteristic Jennings poem presents the ache and exhilaration of romantic yearning expressed in exquisitely controlled rhyme and meter. She acknowledges her own confused romantic longings—emotional, artistic, and religious—but subjects them to lucid analysis. Her goal is not to resolve the contradictions but clarify them.”

Dana says there are two ways to introduce the public to an unfamiliar poet. The first is to describe particular qualities of the work. He opts for Door Number Two:

“The second way to introduce a poet is simpler. Quote the work. Here is the opening of ‘I Feel.’

I feel I could be turned to ice

If this goes on, if this goes on.

I feel I could be buried twice

And still the death not yet be done.

I feel I could be turned to fire

If there can be no end to this.

I know within me such desire

No kiss could satisfy, no kiss.

The poem’s language is direct, musical, and intense. The strict form feels less like an abstract framework than a cauldron barely able to contain its scalding emotions. The poem’s impact is so immediate and tangibly personal that it is easy to miss its quiet but profound engagement with the Catholic literary tradition. The paradoxical combination of ice and fire imagery goes back at least as far as Petrarch. More interesting, however, is the poem’s connections to Christian mysticism. Although “I Feel” initially seems an expression of erotic longing poisoned by despair, close examination reveals it can also be read as a tortured expression of spiritual hunger, the mystic’s excruciating desire for rapturous union with God.

Dana with Doctor Gatsby. (Photo: Star Black)

She was prodigiously productive, and produced great poems at every stage of her life. Yet her Catholic religion set her apart as much as being being a woman did: “Jennings’s literary reputation never surmounted the limits imposed on women of her generation. By the time of her death in 2001, the situation for female writers had become less grim, but her Catholicism isolated her from the feminist vanguard leading the cultural change. In her later years, reviewers often treated her with condescension and hostility. One young critic mocked her as a ‘Christian lady’ and ’emotional anchorite’ inhabiting a world of ‘shapeless woolens, small kindnesses and quiet deaths’ —an odious remark even by the snotty standards of British reviewing. Jennings understood the dilemma and bore it, but not without a touch of bitterness. (Few Catholic poets extend the concept of redemptive suffering to include their own bad reviews.)”

Read the whole thing here.

Tags: "Dana Gioia", Elizabeth Jennings