Letters as “a listening device, a means of silent communion, a snare or net”: wise words from Andrei Sinyavsky

Sunday, June 10th, 2018

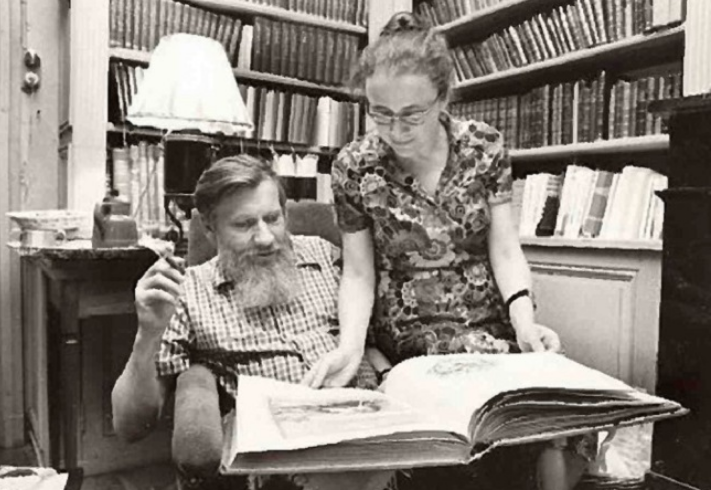

Sinyavsky reunited with the woman who was waiting on the other side.

I’ve been laboring over a text on Russian prosody this weekend, so Russia is clearly still on my mind, even after Friday night’s post on “Eating and (mostly) drinking with Dostoevsky.” However, in an idle moment I turned to yesterday’s post over at Anecdotal Evidence, and apparently Russia is on blogger Patrick Kurp‘s mind, too. I didn’t think many others in the West remembered Andrei Sinyavsky, who wrote under the pen name borrowed from a Russian-Jewish gangster, Abram Tertz (a move that didn’t keep him from getting arrested).

As Patrick explains: “In 1966 he was sentenced to seven years of forced labor for trying to ‘subvert or weaken the Soviet regime.’ That is, he sent a pamphlet and stories to Paris for publication. Totalitarian regimes pay writers the compliment of taking their work seriously. Modern democracies don’t care, and let’s hope it stays that way.” Let’s hope indeed. Sinyavsky was freed in 1971, and emigrated to Paris, where he died in 1997.

As Patrick explains: “In 1966 he was sentenced to seven years of forced labor for trying to ‘subvert or weaken the Soviet regime.’ That is, he sent a pamphlet and stories to Paris for publication. Totalitarian regimes pay writers the compliment of taking their work seriously. Modern democracies don’t care, and let’s hope it stays that way.” Let’s hope indeed. Sinyavsky was freed in 1971, and emigrated to Paris, where he died in 1997.

Patrick, in turn, was inspired by a web article a few days ago by John Wilson, the founding editor of Books & Culture. Also worth a read.

All this returned me to my own well-worn 1976 copy of A Voice from the Chorus (translated by Kyril Fitzlyon and Max Hayward), with my London phone number scribbled in the front cover. I can’t remember when or for whom I wrote a review. I just remember the book reshuffling my internal dynamics.

These are Sinyavsky’s letters from a labor camp. He was allowed to write to his wife Maria Rozanova only twice a month. The book is poignantly fragmentary – sometimes a sentence or a words overheard in the camp, sometimes the words spill into a mini-essay of several pages. The inside front cover of my book is full of penciled notes for passages I wanted to remember, like this one:

What makes us what we are? It probably all depends on our relationship to surrounding space. A man unconfined in space constantly aspires to go forward into the distance. He is sociable and aggressive, and needs ever new pleasures, impressions and interests. But if he is constricted, cut down to size, reduced to the minimum, then his mind, deprived of forests and fields, creates an inner landscape out of its own immeasurable resources. This is something that monks well knew how to take advantage of. To give away all your worldly goods – is not this to throw out ballast?

Not a man, but a well.

We are not outcasts or prisoners, but reservoirs. Not men, but wells, deep pools of meaning.

But above all these are love letters to the woman waiting for him on the other side, year after year. “I often sit down to a letter not because I intend writing anything of importance to you, but just to touch a piece of paper which you will be holding in your hand…”

And here:

“Oddly enough, all this idle chatter in my letters is in large measure not so much self-expression on my part as a form of listening, of listening to you – turning things over this way and that and seeing what you think about them. It is important for me, when I write, to hear you. Language thus becomes a scanning or listening device, a means of silent communion – absolutely empty, a snare or net: a net of language cast into the sea of silence in the hope of pulling up some little golden fish caught in the pauses, in the momentary interstices of silence. Words have no part in this, except in so far as they serve to mark off the pauses. We use them only to jolly ourselves along as we make our way towards silence, perfect silence.”