How Andrei Sinyavsky’s papers wound up at Stanford – and a long-ago trip to Fountenay-aux-Roses to get them.

Monday, June 11th, 2018

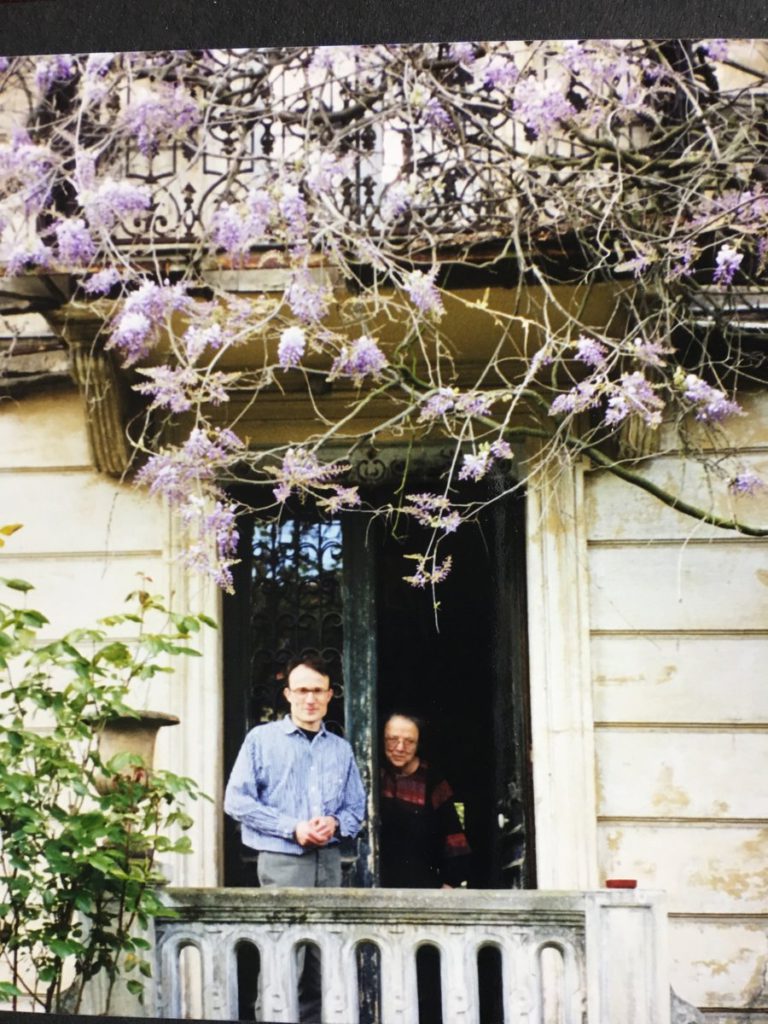

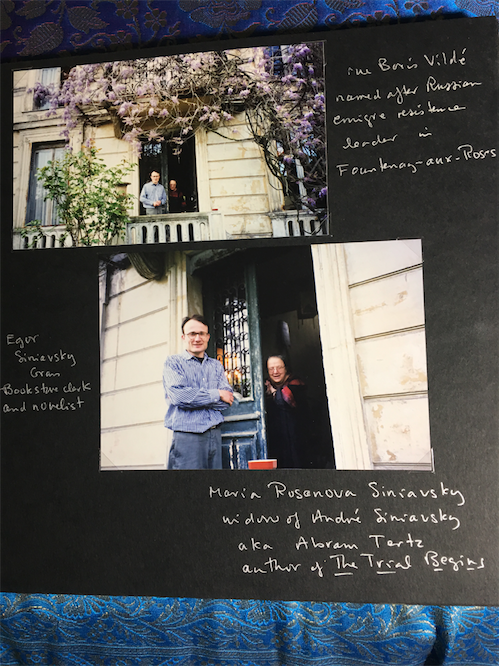

Mother, son, and wisteria at the rue Boris Vilde.

It’s a small world, of course. And even smaller if you’re at Stanford. No sooner had I posted yesterday’s thoughts about the Russian writer Andrei Sinyavsky (pen name Abram Tertz), then a tweet surfaced in cyberspace from a dear friend: “”Cynthia Haven brought back memories of reading Abram Tertz, then meeting him in the Hoover Archives reading room as Sinyavsky. Both he and his wife Maria Rozanova were regulars in the Hoover Archives reading room in the 1990s. They just could not stay away.” No wonder. With its extensive collections on the Soviet era, it would have been a miracle to them.

Elena Danielson, the friend, and also the former director of the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, told me that Hoover had, in fact, acquired the papers of Sinyavsky, and she herself had collected them from France.

I noodled around google a bit and found the Stanford press release from October 1998. It’s another story of Hoover’s truly remarkable archival rescue efforts:

The Hoover Institution has acquired the papers of the Russian writer and human rights activist Andrei Siniavski. Siniavski’s writings and his trial for allegedly publishing anti-Soviet slander in foreign countries are considered key in mobilizing the human rights movement that contributed in significant ways to the forces that discredited and toppled the Soviet system. “Siniavski was a writer whose fiction provoked the regime to frenzy and galvanized the movement that eventually brought it down,” said Hoover Institution Senior Research Fellow Robert Conquest after hearing about the acquisition.

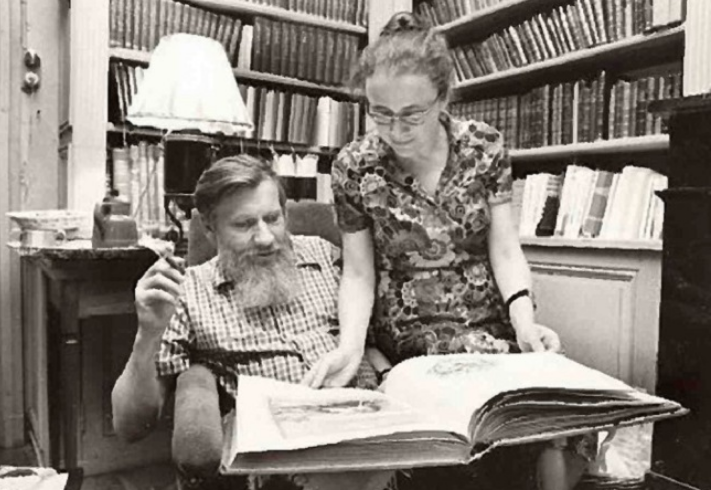

Beginning in the 1950s, Siniavski sent abroad writings under the pseudonym Abram Tertz that he could not publish legally in the Soviet Union. He was arrested in 1965, tried in 1966 and sentenced to forced labor.

Demonstrations against the trial galvanized young intellectuals, among them Vladimir Bukovsky and Alexander Ginzburg, and inducted them into the human rights movement. In response to international protests at Siniavski’s mistreatment, the regime allowed him to emigrate to France in 1973.

Siniavski’s wife, Maria Rozanova, also publicized her husband’s plight and refused to leave the Soviet Union without his papers. Authorities relented in order to dispatch her abroad, and she was able to save the record of her husband’s life and work.

Once in the west, Siniavski taught at the Sorbonne, served as a visiting professor at Stanford and received an honorary doctorate from Harvard. He died in 1977. [Correction: it was 1997.]

The collection contains biographical information on Siniavski and his father, who was arrested for political activity; unpublished manuscripts and correspondence from before his arrest; materials on smuggling his manuscripts abroad, including secret codes he used; evidence of his influence on students at Moscow University; evidence of people spying on him; materials on his arrest and trial; a copy of the KGB interrogation files, notes on the search of his home and photographs from the early days of the human rights movement; papers from the emigration and continuing human rights activities abroad, including broadcasts for Radio Liberty and tapes of complete interviews and sections not broadcast; and papers on emigre politics.

The collection contains biographical information on Siniavski and his father, who was arrested for political activity; unpublished manuscripts and correspondence from before his arrest; materials on smuggling his manuscripts abroad, including secret codes he used; evidence of his influence on students at Moscow University; evidence of people spying on him; materials on his arrest and trial; a copy of the KGB interrogation files, notes on the search of his home and photographs from the early days of the human rights movement; papers from the emigration and continuing human rights activities abroad, including broadcasts for Radio Liberty and tapes of complete interviews and sections not broadcast; and papers on emigre politics.

“The trip to rue Boris Vilde was such fun, about 1998 I suppose,” Elena recalled. “The wisteria covered house was classic French, and the interior, stuffed with papers on make-shift shelving, was so very Russian. The son, Iegor Sinyavsky Gran, is a novelist and a charming guy.”

She went back to her notebooks and files to find some photos for me.

“Maria Rosanova and Iegor Sinyavsky, rue Boris Vilde, Fountenay-aux-Roses,…I’ve just found the wisteria-covered house, stuffed with the late Andre Siniavsky’s papers in boxes, on shelves, overflowing the furnitures…Maria looked around in despair ‘Bumagi, bumagi, bumagi…'” (That would be бумаги, бумаги, бумаги. Or “papers, papers, papers…” to the rest of us.)

Elena

“The widow was totally bewildered by the huge stacks of papers,” she recalled. “But we got it all shipped and cataloged.” Then, a little later, “Such charm. The two of them made the collecting trip into one of the highlights of my career.” I could almost hear her sigh, all the way from Twitterland.

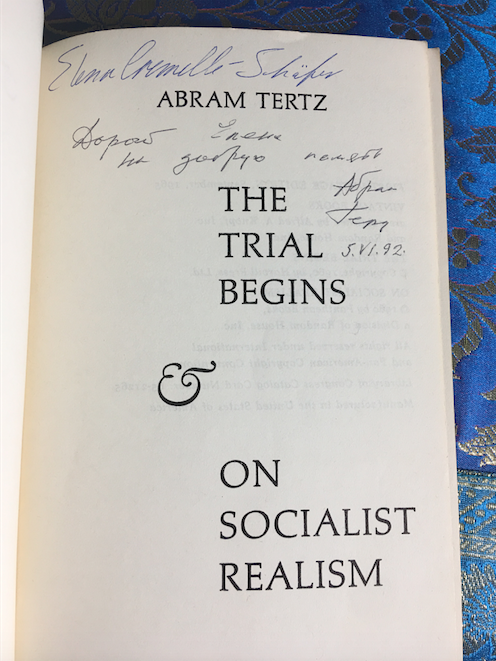

And she had another souvenir in her house from his days at Hoover, way back in the 1990s. She explained: “I bought The Trial Begins with an intro by Czesław Miłosz for a class at Berkeley, so in the 1965-1969 era. I just found the book which he autographed for me in the Hoover Archives reading room, dated 1992. He signed it Abram Tertz.

More from Elena’s albums:

As Patrick explains: “In 1966 he was sentenced to seven years of forced labor for trying to ‘subvert or weaken the Soviet regime.’ That is, he sent a pamphlet and stories to Paris for publication. Totalitarian regimes pay writers the compliment of taking their work seriously. Modern democracies don’t care, and let’s hope it stays that way.” Let’s hope indeed. Sinyavsky was freed in 1971, and emigrated to Paris, where he died in 1997.

As Patrick explains: “In 1966 he was sentenced to seven years of forced labor for trying to ‘subvert or weaken the Soviet regime.’ That is, he sent a pamphlet and stories to Paris for publication. Totalitarian regimes pay writers the compliment of taking their work seriously. Modern democracies don’t care, and let’s hope it stays that way.” Let’s hope indeed. Sinyavsky was freed in 1971, and emigrated to Paris, where he died in 1997.