Russian author Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) was apparently free with his advice. Maria Popova over at “Brainpickings” found Chekov’s 1886 letter to his older brother Nikolai, an artist. We can only imagine how well the advice was received. After all, the letter is written to an older brother, when Anton was 26 and Nikolai 28. In any case, the older brother died three years later of tuberculosis.

As for our humble selves, we can only quote Elizabeth Bennet, in the conversation with Mr. Darcy, Mr. Bingley, and Bingley’s sister Caroline Bingley, from Jane Austen‘s Pride and Prejudice:

Sensible lady

“It is amazing to me,” said Bingley, “how young ladies can have patience to be so very accomplished as they all are.”

“All young ladies accomplished! My dear Charles, what do you mean?”

“Yes, all of them, I think. They all paint tables, cover screens, and net purses. I scarcely know anyone who cannot do all this, and I am sure I never heard a young lady spoken of for the first time, without being informed that she was very accomplished.”

“Your list of the common extent of accomplishments,” said Darcy, “has too much truth. The word is applied to many a woman who deserves it no otherwise than by netting a purse or covering a screen. But I am very far from agreeing with you in your estimation of ladies in general. I cannot boast of knowing more than half-a-dozen, in the whole range of my acquaintance, that are really accomplished.”

“Nor I, I am sure,” said Miss Bingley.

“Then,” observed Elizabeth, “you must comprehend a great deal in your idea of an accomplished woman.”

“Yes, I do comprehend a great deal in it.”

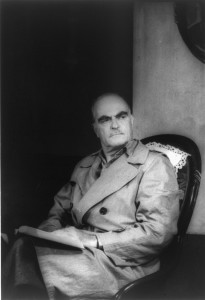

He looked the part. (Osip Braz portrait, 1898)

“Oh! certainly,” cried his faithful assistant, “no one can be really esteemed accomplished who does not greatly surpass what is usually met with. A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word; and besides all this, she must possess a certain something in her air and manner of walking, the tone of her voice, her address and expressions, or the word will be but half-deserved.”

“All this she must possess,” added Darcy, “and to all this she must yet add something more substantial, in the improvement of her mind by extensive reading.”

“I am no longer surprised at your knowing only six accomplished women. I rather wonder now at your knowing any.”

Well, then. That’s almost as long as Chekhov’s letter from Moscow. He begins with the good news: “You have often complained to me that people “don’t understand you”! Goethe and Newton did not complain of that…. Only Christ complained of it, but He was speaking of His doctrine and not of Himself…. People understand you perfectly well. And if you do not understand yourself, it is not their fault.

“I assure you as a brother and as a friend I understand you and feel for you with all my heart. I know your good qualities as I know my five fingers; I value and deeply respect them. If you like, to prove that I understand you, I can enumerate those qualities. I think you are kind to the point of softness, magnanimous, unselfish, ready to share your last farthing; you have no envy nor hatred; you are simple-hearted, you pity men and beasts; you are trustful, without spite or guile, and do not remember evil…. You have a gift from above such as other people have not: you have talent. This talent places you above millions of men, for on earth only one out of two millions is an artist. Your talent sets you apart: if you were a toad or a tarantula, even then, people would respect you, for to talent all things are forgiven.”

Then the bad news: “You have only one failing, and the falseness of your position, and your unhappiness and your catarrh of the bowels are all due to it. That is your utter lack of culture. Forgive me, please, but veritas magis amicitiae…. You see, life has its conditions. In order to feel comfortable among educated people, to be at home and happy with them, one must be cultured to a certain extent. Talent has brought you into such a circle, you belong to it, but … you are drawn away from it, and you vacillate between cultured people and the lodgers vis-a-vis.”

Then the list:

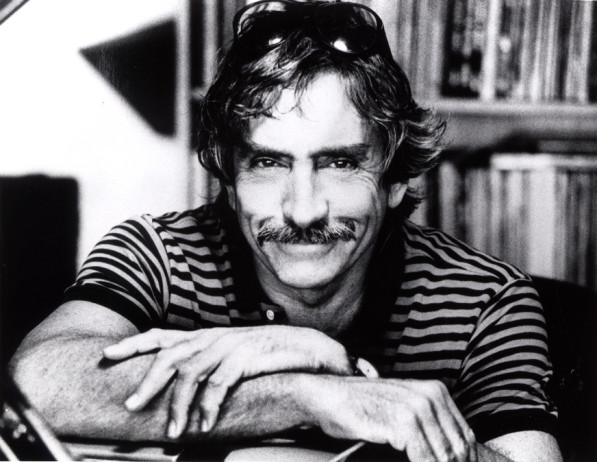

Anton and his artist brother in 1882.

Cultured people must, in my opinion, satisfy the following conditions:

- They respect human personality, and therefore they are always kind, gentle, polite, and ready to give in to others. They do not make a row because of a hammer or a lost piece of india-rubber; if they live with anyone they do not regard it as a favour and, going away, they do not say “nobody can live with you.” They forgive noise and cold and dried-up meat and witticisms and the presence of strangers in their homes.

- They have sympathy not for beggars and cats alone. Their heart aches for what the eye does not see…. They sit up at night in order to help P…. [here a mediocre poet is named], to pay for brothers at the University, and to buy clothes for their mother.

- They respect the property of others, and therefor pay their debts.

- They are sincere, and dread lying like fire. They don’t lie even in small things. A lie is insulting to the listener and puts him in a lower position in the eyes of the speaker. They do not pose, they behave in the street as they do at home, they do not show off before their humbler comrades. They are not given to babbling and forcing their uninvited confidences on others. Out of respect for other people’s ears they more often keep silent than talk.

- They do not disparage themselves to rouse compassion. They do not play on the strings of other people’s hearts so that they may sigh and make much of them. They do not say “I am misunderstood,” or “I have become second-rate,” because all this is striving after cheap effect, is vulgar, stale, false….

- They have no shallow vanity. They do not care for such false diamonds as knowing celebrities, shaking hands with the drunken P., [Translator’s Note: Probably Palmin, a minor poet.] listening to the raptures of a stray spectator in a picture show, being renowned in the taverns…. If they do a pennyworth they do not strut about as though they had done a hundred roubles’ worth, and do not brag of having the entry where others are not admitted…. The truly talented always keep in obscurity among the crowd, as far as possible from advertisement…. Even Krylov has said that an empty barrel echoes more loudly than a full one.

- If they have a talent they respect it. They sacrifice to it rest, women, wine, vanity…. They are proud of their talent…. Besides, they are fastidious.

- They develop the aesthetic feeling in themselves. They cannot go to sleep in their clothes, see cracks full of bugs on the walls, breathe bad air, walk on a floor that has been spat upon, cook their meals over an oil stove. They seek as far as possible to restrain and ennoble the sexual instinct…. What they want in a woman is not a bed-fellow … They do not ask for the cleverness which shows itself in continual lying. They want especially, if they are artists, freshness, elegance, humanity, the capacity for motherhood…. They do not swill vodka at all hours of the day and night, do not sniff at cupboards, for they are not pigs and know they are not. They drink only when they are free, on occasion…. For they want mens sana in corpore sano [a healthy mind in a healthy body].

And so on. This is what cultured people are like. In order to be cultured and not to stand below the level of your surroundings it is not enough to have read The Pickwick Papers” and learnt a monologue from Faust. …

What is needed is constant work, day and night, constant reading, study, will…. Every hour is precious for it…. Come to us, smash the vodka bottle, lie down and read…. Turgenev, if you like, whom you have not read.

You must drop your vanity, you are not a child … you will soon be thirty.

It is time!

I expect you…. We all expect you.

I’m working rather feverishly to finish writing against an important and non-negotiable deadline, and began two blog posts to you, Faithful Readers, but got strangely tangled up in my own words and couldn’t finish. Nevertheless I finally got a chance at last to read poet Dana Gioia‘s discussion of Anton Chekhov’s 1899 short story, “The Lady with the Pet Dog.” His thoughts about it are over at his website here. In the course of it, he writes, the hero (if you can call him that) “undergoes a strange and winding course of emotional and moral growth that few readers would expect.” Vladimir Nabokov called it “one of the greatest stories ever written.”

I’m working rather feverishly to finish writing against an important and non-negotiable deadline, and began two blog posts to you, Faithful Readers, but got strangely tangled up in my own words and couldn’t finish. Nevertheless I finally got a chance at last to read poet Dana Gioia‘s discussion of Anton Chekhov’s 1899 short story, “The Lady with the Pet Dog.” His thoughts about it are over at his website here. In the course of it, he writes, the hero (if you can call him that) “undergoes a strange and winding course of emotional and moral growth that few readers would expect.” Vladimir Nabokov called it “one of the greatest stories ever written.”