A rabbi’s P.O.V.: Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s conversion is social, not doctrinal

Sunday, November 19th, 2023

“Wherever you go, I will go…your people will be my people.” Ruth converts, as does Ali, not because Naomi convinces her that Judaism is doctrinally right, but because she is impressed by Naomi’s character and wants to join her culture.” ~ Zohar Atkins

Much ink has already been spilled on Ayaan Hirsi Ali‘s conversion to Christianity, which she announced in the online journal Unherd a week ago. It was less of a surprise to me, perhaps. During my interview with the Somali-born activist six years ago, published in Stanford Magazine as “To Change People’s Minds”, she made an offhand, slightly dismissive remark about Christianity in passing, and I told her I was one of “them.” She was momentarily off balance, startled, apologetic – and for a brief instant we were both wide awake and open. And then it passed.

My first encounter with her was a dozen years ago, as I attended an onstage interview in Palo Alto with writer Susanne Pari as interlocutor. The two women were discussing terrorism, and Pari brought up the case of Faisal Shahzad, an apparently assimilated Muslim who turned to jihad and attempted to bomb Times Square. But Hirsi Ali interrupted Pari’s comments about his job loss as a possible motive for his actions.

“I have a problem with that,” she said. “If we even remotely entertain’the notion that foreclosure and health care and normal adversity is an excuse to take away the life of another, then,“ she said, “we are really going down.”

“He has a freaking MBA!” she exploded. “I know people who can’t read!” Hirsi Ali denied that “the only therapy is to get an SUV and fill it with explosives.” Nor did she excuse Nidal Malik Hasan, who “got to be a major in a voluntary army.”

“Why don’t we take these people at their word? ” she asked. “Why don’t we examine their convictions?”

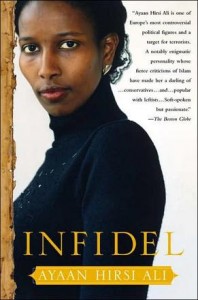

Pari noted that, in her Iran-American childhood, there was only one mosque in the nation, in Washington D.C., and now there are thousands (“1150,” corrected Hirsi Ali). She took Hirsi Ali, a fellow atheist, to task for the conclusion of her book Infidel, in which she suggests that the love and tolerance exhibited in much of Christianity might be a force to subdue Islam. “I was very naughty!” Hirsi Ali admitted with a chuckle.

Pari said the very idea “was disturbing to me, frankly…What were you thinking?”

Ayaan Hirsi Ali – who lives under a fatwa, still – responded in a beat: “The superficial answer is, if every Muslim became Christian, I would live without bodyguards.”

Back to the present. Over at Zohar Atkins‘s substack, What Is Called Thinking, the rabbi, poet, and theologian argues that “Religion is Social,” and that in fact Ayaan converted to Christianity … via Judaism. (You can catch my podcast with him, “From Envy to Forgiveness,” here.)

He begins:

Outspoken New Atheist Aayan Hirsi Ali has converted to Christianity, but her arguments are more psychological and consequentialist than fundamentalist—she makes no mention of Christian dogma or creed. Instead, she focuses on her own need for meaning and her appreciation for the legacy of Christian culture and civilization when compared to other alternatives. Her conversion story thus bothered Christians and atheists alike. The former, because they felt she had failed to address the question of the truth of Christian doctrine; the latter because they felt she had failed to address the untruth of it. Ross Douthat wrote a compelling piece on her conversion that points to a lacuna in her conversion story, aside from the truth question: “the weirdness of religious experience.” She didn’t just convert because religion is a source of meaning, he says, but because the strangeness of religious experience provokes a recognition that the world itself is strange.

Speaking from a Jewish perspective, the hardline distinction between the truth of a religion, its practical civilizational value, and its psychological import falls away. Both Ali’s Christian critics and atheist critics take too shallow (though possibly an appropriately Protestant) view of religion. In the story of Ruth’s conversion to Judaism, now the paradigmatic script for all Jewish converts, we note that her motivations are primarily social and relational. “Wherever you go, I will go…your people will be my people.” Ruth converts, as does Ali, not because Naomi convinces her that Judaism is doctrinally right, but because she is impressed by Naomi’s character and wants to join her culture.

Jews read the story of Ruth on Shavuot, the Holiday that celebrates the Revelation at Sinai, because the distinction between divine revelation and interdependent communal formation are two sides of the same coin. Some people join because of supernatural experience, per Douthat’s point. But some join because they like the people who have supernatural experience. Or better yet, sitting at the table of deeply kind, deeply thoughtful, deeply inspiring people can itself be a kind of supernatural experience — even if it requires no belief in virgin births or split seas. In the middle ages, Maimonides pushed to shore up Jewish theology along 13 principles of faith, but historically Judaism has drawn friends and converts not because people agreed with these logical and abstract principles but because it has impressed them as a way of life.

Read the whole thing here. It’s wonderful and worth it.