Claude Lanzmann and the “fiction of the real.”

Friday, July 6th, 2018

In 2014 (Photo: ActuaLitté)

Claude Lanzmann died yesterday. He was 92. Obituaries usually slide towards eulogy, so I was interested when the New York Public Library’s Paul Holdengräber drew my attention instead to a 2012 review of Lanzmann’s The Patagonian Hare: A Memoir. Lanzmann, a French Jew, had joined the Résistance at 17. After the war, he had the distinction of being, for seven years, “the only man with whom Simone de Beauvoir lived a quasi-marital existence.” He was also a friend of Jean-Paul Sartre.

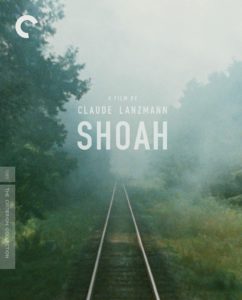

He was, of course, best known for his 1985 film Shoah. According to reviewer Adam Shatz: “released in 1985 after more than a decade of labour, is a powerful nine and a half hour investigation, composed almost entirely of oral testimony. Neither a conventional documentary nor a fictional re-creation but, as Lanzmann called it, ‘a fiction of the real’, Shoah revealed the way the Holocaust reverberated, as trauma, in the present.”

He was asked by the Israeli government to make not a film about the Shoah, “but a film that is the Shoah.” Lanzmann accepted the assignment.

Until the 1960s, Israel had shown little interest in the Holocaust. The survivors, their stories, the Yiddish many of them spoke – these were all seen as shameful reminders of Jewish weakness, of the life in exile that the Jewish state had at last brought to an end. But with the Eichmann trial, and particularly after the 1967 war, Israel discovered that the Holocaust could be a powerful weapon in its ideological arsenal. Lanzmann, however, had more serious artistic ambitions for his film than the Foreign Ministry, which, impatient with his slowness, withdrew funding after a few years, before a single reel was shot. Lanzmann turned to the new prime minister, Menachem Begin, who put him in touch with a former member of Mossad, a ‘secret man devoid of emotions’. He promised that Israel would sponsor the film so long as it ran no longer than two hours and was completed in 18 months. Lanzmann agreed to the conditions, knowing he could never meet them. He ended up shooting 350 hours of film in half a dozen countries; the editing alone took more than five years. Despite his loyalty to Israel, his loyalty to Shoah came first, and he was prepared to do almost anything to make it his way.

Shoah is an austere, anti-spectacular film, without archival footage, newsreels or a single corpse. Lanzmann ‘showed nothing at all’, Godard complained. That was because there was nothing to show: the Nazis had gone to great lengths to conceal the extermination; for all their scrupulous record-keeping, they left behind no photographs of death in the gas chambers of Birkenau or the gas trucks in Chelmno. They hid the evidence of the extermination even as it was taking place, weaving pine tree branches into the barbed wire of the camps as camouflage, using geese to drown out cries, and burning the bodies of those who’d been asphyxiated. As Filip Müller – a member of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, the Special Unit of Jews who disposed of the bodies – explains in Shoah, Jews were forced to refer to corpses as Figuren (‘puppets’) or Schmattes (‘rags’), and beaten if they didn’t. Other filmmakers had compensated for the absence of images by showing newsreels of Nazi rallies, or photographs of corpses piled up in liberated concentration camps. Lanzmann chose instead to base his film on the testimony of survivors, perpetrators and bystanders. Their words – often heard over slow, spectral tracking shots of trains and forests in the killing fields of Poland – provided a gruelling account of the ‘life’ of the death camps: the cold, the brutality of the guards, the panic that gripped people as they were herded into the gas chambers.

Shoah is an austere, anti-spectacular film, without archival footage, newsreels or a single corpse. Lanzmann ‘showed nothing at all’, Godard complained. That was because there was nothing to show: the Nazis had gone to great lengths to conceal the extermination; for all their scrupulous record-keeping, they left behind no photographs of death in the gas chambers of Birkenau or the gas trucks in Chelmno. They hid the evidence of the extermination even as it was taking place, weaving pine tree branches into the barbed wire of the camps as camouflage, using geese to drown out cries, and burning the bodies of those who’d been asphyxiated. As Filip Müller – a member of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, the Special Unit of Jews who disposed of the bodies – explains in Shoah, Jews were forced to refer to corpses as Figuren (‘puppets’) or Schmattes (‘rags’), and beaten if they didn’t. Other filmmakers had compensated for the absence of images by showing newsreels of Nazi rallies, or photographs of corpses piled up in liberated concentration camps. Lanzmann chose instead to base his film on the testimony of survivors, perpetrators and bystanders. Their words – often heard over slow, spectral tracking shots of trains and forests in the killing fields of Poland – provided a gruelling account of the ‘life’ of the death camps: the cold, the brutality of the guards, the panic that gripped people as they were herded into the gas chambers.

In The Patagonian Hare, Lanzmann describes the making of Shoah as a kind of hallucinatory voyage, and himself as a pioneer in the desolate ruins of the camps, ‘spellbound, in thrall to the truth being revealed to me … I was the first person to return to the scene of the crime, to those who had never spoken.’ …

Jan Karski makes an appearance in the review:

Karski tried to tell the West.

Defending his depiction of Poland, Lanzmann says that his ‘most ardent supporter’ was Jan Karski, a representative of the Polish government in exile who made two visits to the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942, and reported his findings both to Anthony Eden and to Roosevelt. Until Lanzmann approached him for an interview in 1977, he had not spoken in public of his wartime mission. His appearance in Shoah and in The Karski Report, an addendum released last year, is indeed shattering:

Lanzmann deserves enormous credit for conducting the interview. Karski praised Shoah as ‘the greatest film that has ever been made about the tragedy of the Jews’, but sharply criticised Lanzmann’s failure to interview [Wladislaw] Bartoszewski, [a member of a clandestine network that rescued Polish Jews during the war]. Karski did not say this to defend his people – in his report, he deplored the Poles’ ‘inflexible, often pitiless’ attitude towards their Jewish compatriots – but because he believed Bartoszewski’s absence left the impression that ‘the Jews were abandoned by all of humanity,’ rather than by ‘those who held political and spiritual power’. Karski’s Holocaust was an unprecedented chapter in the history of political cruelty; Lanzmann’s Shoah was an eschatological event in the history of the Jews: incomparable, inexplicable, surrounded by what he called a ‘sacred flame’. ‘The destiny and the history of the Jewish people,’ he said in an interview with Cahiers du Cinéma, ‘cannot be compared to that of any other people.’ Even the hatred aimed at them was exceptional, he said, insisting that anti-semitism was of a different order from other forms of racism.