Dana Gioia on little-known poet Dunstan Thompson: “ambitious, original, mercurial, uneven”

Friday, May 22nd, 2015 Poet Dana Gioia, former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, has performed many good deeds for literature; here’s one that has generally gone unnoticed: he has promoted the work of many little-known poets and writers, both living and dead, who have received fame, acclaim, and wider circulation soon afterwards. In many cases, I think his imprimatur has been decisive. He was one of the early champions for Kay Ryan, the Marin community college teacher who went on to win a Pulitzer and just about every other major poetry award, as well as being named U.S. poet laureate. We can add Kim Addonizio, Weldon Kees, and even Robinson Jeffers to the list.

Poet Dana Gioia, former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, has performed many good deeds for literature; here’s one that has generally gone unnoticed: he has promoted the work of many little-known poets and writers, both living and dead, who have received fame, acclaim, and wider circulation soon afterwards. In many cases, I think his imprimatur has been decisive. He was one of the early champions for Kay Ryan, the Marin community college teacher who went on to win a Pulitzer and just about every other major poetry award, as well as being named U.S. poet laureate. We can add Kim Addonizio, Weldon Kees, and even Robinson Jeffers to the list.

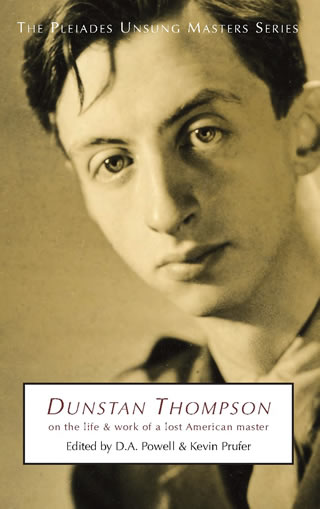

That observation alone would make it worthwhile to pay attention to his article in the current Hudson Review, “Two Poets Named Dunstan Thompson.” Thompson’s not entirely forgotten … at least not anymore. D.A. Powell and Kevin Prufer compiled a tribute volume, Dustan Thompson: On the Life and Work of a Lost American Master in 2010. Later this year, Thompson’s Selected Poems, edited by Gregory Wolfe, will bring his work (we hope) to a wider audience.

The Connecticut-born Thompson (1918-1975) was educated at Harvard and enlisted in the U.S. Army in World War II. Borges translated some of his work after Thompson’s Poems (Simon & Schuster) was published in 1943. His second poetry collection, Lament for the Sleepwalker, appeared in 1946. A 1954 novel, The Dove with the Bough of Olive was not well received. A travel book The Phoenix in the Desert was published in London in 1951. He had published in The New Yorker and The Paris Review, but his next three manuscripts remained unpublished. What happened in the final decades is most interesting.

Dana’s essay is highly recommended; it’s one of his finest. And you get two poets for the price of one. Here’s why:

Two contradictory views of Thompson and his poetry have emerged, which seem to reflect an irreconcilable dichotomy inherent in both his life and work. Each faction has made exclusive claim to his legacy. For one group, Thompson stands as a pioneering poet of gay experience and sensibility. He was one of the first poets—and certainly the best of the World War II era—to write openly about homosexual experience. Although his language remained slightly coded—even straight sex could not be depicted literally at that time without censorship or prosecution—there was little ambiguity about the hidden world of casual sexual encounters he describes so powerfully in his neo-Romantic and rhapsodic poems. An heir to Walt Whitman and Hart Crane, Thompson stood, to quote Jim Elledge, as “a kindred soul” to contemporary gay poets.

To the second group, Thompson ranks as one of the important English-language Catholic poets of the twentieth century. A neo-classical writer of cosmopolitan sensibility, he cultivated an austere and formal style to explore themes of history, culture, and religion. In ways that seem more European than American, the mature Thompson also used the long perspectives of Christian and Classical history to understand the modern world after the devastations, dislocations, and atrocities of a troubled century.

There is no question that Thompson’s poetry falls into two parts—the early work published during the 1940s and the later work gathered posthumously in 1984.

The “vast and insistent threnody” of the first era “transcends its own sentimentality mostly bit its sheer feverish persistence. All of the wrong notes seem small in comparison to its large, symphonic sweep.” The highly musical poems (“The boy that brought me beauty brought me death”) reflect a poet who “reveled in the hypnotic quality of formal rhythms. His mode is essentially rhapsodic – an attempt to cast an emotional spell over the listener.” The second period occurred after he had settled in the obscure Norfolk village of Cley, initially for financial reasons, but then he and his partner, the journalist Philip Trower, stayed and stayed, far away from the mainstream literary world. “If Thompson’s early verse is flamboyantly neb-romantic, the later work is calmly neoclassical. … His style cooled becoming more austere and controlled. The tone shifted from vatic to conversational.” He adopted free verse as another tool in his repertoire, and wrote dramatic monologues, narratives, hymns, satires, epigrams, epistles, devotions, discursive meditations. “The older Thompson obsessively ponders the past as window into the human condition.”

Dana concludes: “Dustan Thompson is not a major poet, but he is also not a minor writer in the conventional sense of doing a few things exquisitely well. He is ambitious, original, mercurial, and uneven in equal measures. His central themes – love, sex, desire, faith, war, and history – are not minor subjects.” Read about both poets – Dunstan Thompson I and Dustan Thompson II – over at The Hudson Review, here.

Refuge: Cley on the River Glaven (Photo: John Beniston)