A neurosurgeon’s road to compassion: “They need each other – the brain and the heart.”

Sunday, July 24th, 2016

The good doctor with the Dalai Lama. (Photo: Firdaus Dhabhar)

Dr. James Doty is one of the more fascinating people I know – I’ve written about him here and here. He is the founder and director of Stanford’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARE, pronounced “see care”), which is at the forefront of a growing movement to bring the tools of psychology and neuroscience to the study of empathy, compassion and altruism. His friend, the Dalai Lama, is one of its benefactors.

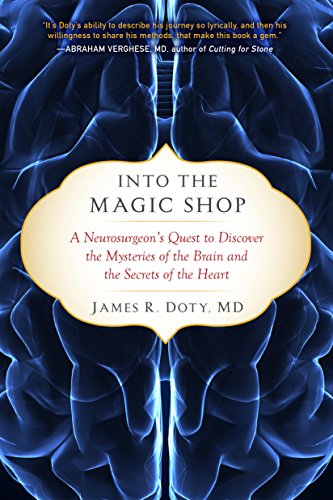

I visited him last week at his office to discuss his brand new book Into the Magic Shop: A Neurosurgeon’s Quest to Discover the Mysteries of the Brain and the Secrets of the Heart, which has quickly climbed the New York Times bestseller list. It’s terrific tale – and he assures me it’s all true. The book begins with his impoverished childhood on the edge of the Mojave Desert, the son of an alcoholic father and clinically depressed and suicidal mother. He describes his struggles to go through medical school, eventually becoming a distinguished neurosurgeon. But most of all, it tells of the important lessons he learned in a magic shop in a rundown strip mall when he was twelve years old.

A video clip of my 2010 interview with him is below. And here’s an excerpt from the introduction:

There’s a certain sound the scalp makes when it’s being ripped of of a skull – like a large piece of Velcro tearing away from it’s source. The sound is loud and angry and just a little bit sad. In medical school they don’t have a class that teaches you the sounds and smells of brain surgery. They should. The drone of the heavy drill as it bores through the skull. The bone saw that fills the operating room with the smell of summer sawdust as it carves a line connecting the burr holes made from the drill. The reluctant popping sound the skull makes as it is lifted away from the dura, the thick sac that covers the brain and serves as its last line of defense against the outside world. The scissors slowly slicing through the dura. When the brain is exposed you can see it move in rhythm with every heartbeat, and sometimes it seems that you can year it moan in protest at its own nakedness and vulnerability – its secrets exposed for all to see under the harsh lights of the operating room.

The boy looks small in the hospital gown and is almost swallowed up by the bed as he’s waiting to enter surgery.

The boy looks small in the hospital gown and is almost swallowed up by the bed as he’s waiting to enter surgery.

“My nana prayed for me. And she prayed for you too.”

I hear the boy’s mother inhale and exhale loudly at this information, and I know she’s trying to be brave for her son. For herself. Maybe even for me. I run my hand through his hair. It is brown and long and fine – still more baby than boy. He tells me he just had a birthday.

“Do you want me to explain again what’s going to happen today, Champ, or are you ready?” He likes it when I call him Champ or Buddy.

“I’m going to sleep. You’re going to take the Ugly Thing out of my head so it doesn’t hurt anymore. Then I see my mommy and nana.”

The “Ugly Thing” is a medulloblastoma, the most common malignant brain tumor in children, and is located in the posterior fossa (the base of the skull). Medulloblastoma isn’t an easy word for an adult to pronounce, much less a four-year-old, no matter how precocious. Pediatric brain tumors really are ugly things, so I’m OK with the term. Medulloblastomas are misshapen and often grotesque invaders in the exquisite symmetry of the brain. They begin between the two lobes of the cerebellum and grow, ultimately compressing not only the cerebellum but also the brainstem, until finally blocking the pathways that allow the fluid in the brain to circulate. The brain is one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen, and to explore its mysteries and find ways to heal it is a privilege I have never taken for granted. …

I know both Mom and Grandma are scared. I hold each of their hands in turn, trying to reassure them and offer comfort. It’s never easy. A little boy’s morning headaches have become every parent’s worst nightmare. Mom trusts me. Grandma trusts God. I trust my team.

Together we will all try to save this boy’s life.

***

Benefactor. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

The surgeon assisting me is a senior resident in training and new to the team, but he is just as focused on the blood vessels, and brain tissue, and minutiae of removing this tumor as I am. We can’t think about our plans for the next day, or hospital politics, or our children, or our relationship trouble at home. It’s a form of hypervigilance, a single-pointed concentration almost like meditation. We train the mind and the mind trains the body. There’s an amazing rhythm and flow when you have a good team – everyone is in sync. Our minds and bodies work together as one coordinated intelligence.

I am removing the last piece of the tumor, which is attached to one of the major draining veins deep in the brain. The posterior fossa venous system is incredibly complex, and my assistant is suctioning fluids as I carefully resect the final remnant of the tumor. He lets his attention wander for a second, and in that second his suction tears the vein, and for the briefest moment everything stops.

Then all hell breaks loose.

The blood from the ripped vein fills the resection cavity, and blood begins to pour out of the wound of this beautiful little boy’s head. The anesthesiologist starts yelling that the child’s blood pressure is rapidly dropping and he can’t keep up with the blood loss. I need to clamp the vein and stop the bleeding, but it has retracted into a pool of blood, and I can’t see it. My suction alone can’t control the bleeding and my assistant’s hand is shaking too much to be of any help.

“He’s in full arrest!” the anesthesiologist screams. He has to scramble under the table because this little boy’s head is locked in a head frame, prone, with the back of his head opened up. The anesthesiologist starts compressing the boy’s chest while holding his other hand on his back, trying desperately to get his heart to start pumping. Fluids are being poured into the large IV lines. The heart’s first and most important job is to pump blood, and this magical pump that makes everything in the body possible has stopped. This four-year-old boy is bleeding to death on the table in front of me. As the anesthesiologist pumps on his chest, the wound continues to fill with blood. We have to stop the bleeding or he will die. The brain consumes 15 percent of the outflow of the hear and can survive only minutes after the heart stops. It needs blood and, more important, the oxygen that is in the blood. We are running out of time before the brain dies – they need each other – the brain and the heart.

(What happens? Read the rest of the story below…)