Emmerich’s film Anonymous: a time tunnel in the opposite direction

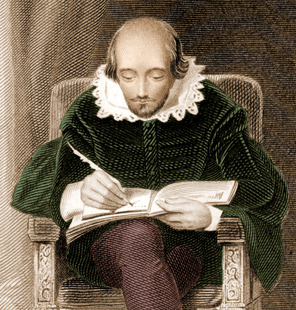

Wednesday, January 4th, 2012 Ruth Kaplan finally got talked into viewing Anonymous, the film about William Shakespeare that is heavy on speculation and very short of facts (we wrote about it earlier in “Shakespeare or the Earl of Oxford? ‘It’s a shame sometimes that dead men can’t sue’ here). She already knew some of the atrocities in advance: for example, the notion that Christopher Marlowe was devoured with his jealousy of Hamlet. It was, in fact, written seven years after Marlowe was murdered.

Ruth Kaplan finally got talked into viewing Anonymous, the film about William Shakespeare that is heavy on speculation and very short of facts (we wrote about it earlier in “Shakespeare or the Earl of Oxford? ‘It’s a shame sometimes that dead men can’t sue’ here). She already knew some of the atrocities in advance: for example, the notion that Christopher Marlowe was devoured with his jealousy of Hamlet. It was, in fact, written seven years after Marlowe was murdered.

Over at Arcade, she wrote:

“Anonymous also makes unsupported allegations, suggesting, for instance, that Shakespeare never learned to write the alphabet. The film sees conspiracy in unremarkable events: the introduction makes the (dubious) assertion that we have not a single manuscript in Shakespeare’s hand, as if this is proof of a cover-up, as opposed to a norm for texts from that era.”

She’s also disturbed by the portrait of Queen Elizabeth as a hysterical, lovesick cougar, disinterested in the realm she governs. And she’s scornful of the notion that an Elizabethan provincial boy couldn’t read (Elizabethan grammar schools were crackerjack – David Riggs discusses that here.)

But what really got her was the retrograde fantasy of an entire era, “its ridicule of the very idea of social mobility. Shakespeare’s desire to raise his social status is represented as vulgar.”

What does it all mean?

So far, she sounds like a lot of people who have seen the movie. Then she adds a wholly different twist:

Social mobility in modern-day America is now at an all time low. The gulf between those who go to college and those who don’t continues to widen. Americans continue to resent women in power, and to resist placing them there: think of the response to Hillary Clinton during her presidential campaign, or look at the US Senate, where only seventeen women serve. As for culture making, in 2010, only 7% of directors of domestic films were women. Despite the progress that has been made, we continue to battle as a nation over how to represent and accord rights to non-straight citizens. As an openly gay German, Roland Emmerich is perhaps an odd director of this portrait of power. Yet his movie not only mirrors the reality of power in our country, it consolidates and perpetuates the heterosexism, misogyny, and class bias that help maintain that reality.

The upshot? “Anonymous may well be the portrait of an age, but it’s not Shakespeare’s.”

It’s good stuff. Read the rest here.