Should we trust Amazon to create our future?

Saturday, September 22nd, 2018Amazon now employs more than half a million people and earlier this month briefly became second company to be worth a trillion dollars. It powers much of the internet through its cloud computing division. “As consumers, as users, we love these tech companies,” says lawyer Lina Khan. “But as citizens, as workers, and as entrepreneurs, we recognize that their power is troubling. We need a new framework, a new vocabulary for how to assess and address their dominance.”

An excerpt from the article:

If competitors tremble at Amazon’s ambitions, consumers are mostly delighted by its speedy delivery and low prices. They stream its Oscar-winning movies and clamor for the company to build a second headquarters in their hometowns. Few of Amazon’s customers, it is safe to say, spend much time thinking they need to be protected from it.

But then, until recently, no one worried about Facebook, Google or Twitter either. Now politicians, the media, academics and regulators are kicking around ideas that would, metaphorically or literally, cut them down to size. Members of Congress grilled social media executives on Wednesday in yet another round of hearings on Capitol Hill. Not since the Department of Justice took on Microsoft in the mid-1990s has Big Tech been scrutinized like this.

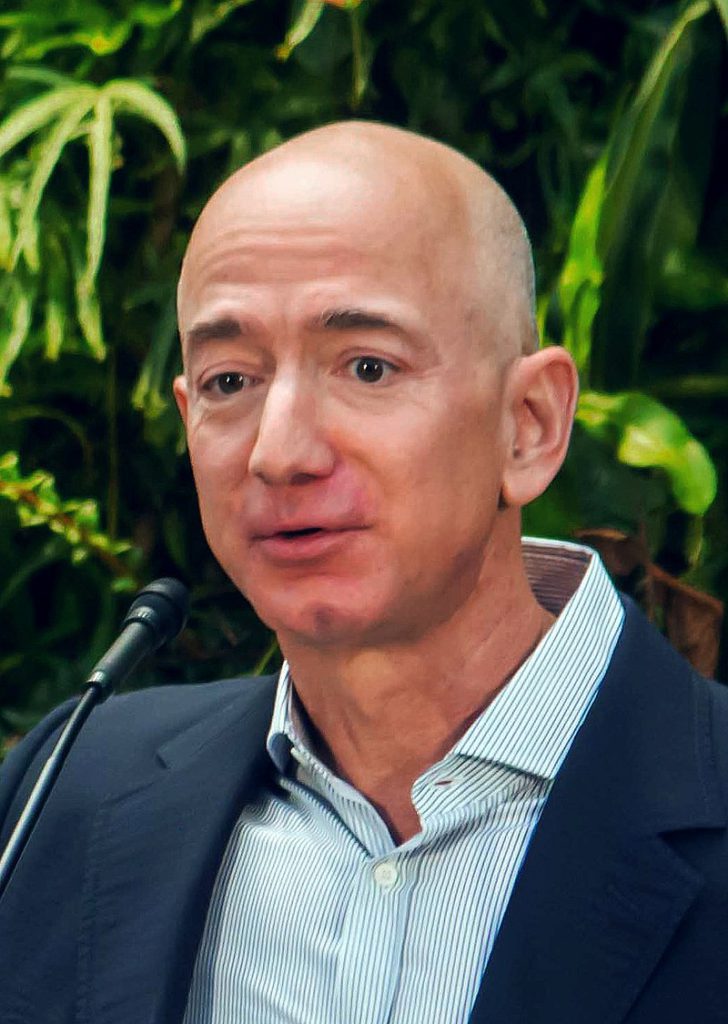

Power man (Photo: Seattle City Council)

Amazon has more revenue than Facebook, Google and Twitter put together, but it has largely escaped sustained examination. That is beginning to change, and one significant reason is Ms. Khan.

Many think it should be exempt from federal intervention. She disagrees, arguing in a Yale Law Journal article that that “the company should not get a pass on anticompetitive behavior just because it makes customers happy. Once-robust monopoly laws have been marginalized, Ms. Khan wrote, and consequently Amazon is amassing structural power that lets it exert increasing control over many parts of the economy.”

Amazon has so much data on so many customers, it is so willing to forgo profits, it is so aggressive and has so many advantages from its shipping and warehouse infrastructure that it exerts an influence much broader than its market share. It resembles the all-powerful railroads of the Progressive Era, Ms. Khan wrote: “The thousands of retailers and independent businesses that must ride Amazon’s rails to reach market are increasingly dependent on their biggest competitor.”

The paper got 146,255 hits, a runaway best-seller in the world of legal treatises. That popularity has rocked the antitrust establishment, and is making an unlikely celebrity of Ms. Khan in the corridors of Washington.

She’s a woman to watch. Politico just named her one of the Politico 50, “its annual list of the people driving the ideas driving politics.”

Read the whole thing here.

He got what he wanted and didn’t want. One way to measure his posthumous fame is to note an interview he did with Rolling Stone, which was never published in 1996 but became the basis for a story after his suicide that won a National Magazine Award in 2009. The interview transcript became a bestselling book in 2010 and then a very unlikely movie – who ever heard of a movie about an interview with a writer? – in 2015. The Wallace estate firmly distanced itself from

He got what he wanted and didn’t want. One way to measure his posthumous fame is to note an interview he did with Rolling Stone, which was never published in 1996 but became the basis for a story after his suicide that won a National Magazine Award in 2009. The interview transcript became a bestselling book in 2010 and then a very unlikely movie – who ever heard of a movie about an interview with a writer? – in 2015. The Wallace estate firmly distanced itself from

As David wrote to me when he sent the link, “bro – he lives!” Then he added, “anyway, what was it exactly they used to call him? joe the bro, no? it was a play off ‘joe the pro.'”

As David wrote to me when he sent the link, “bro – he lives!” Then he added, “anyway, what was it exactly they used to call him? joe the bro, no? it was a play off ‘joe the pro.'”