Australian poet Les Murray is dead at 80: “The deadliest inertia is to conform with your times” – and he didn’t.

Tuesday, April 30th, 2019The Nobel evaded him, and now he shall never get it, though he was considered among the greatest poets of our era. The Australian poet Les Murray died peacefully yesterday at 80. In 2012, the National Trust of Australia classified Murray as one of Australia’s 100 living treasures, but he was much more than that, from the beginning.

David Mason, writing in today’s First Things: “Murray grew up in dire poverty on a farm with no electricity or running water, and always felt exiled from the privileged classes. Largely self-educated, at university he was so poor he ate the scraps he found on plates in the cafeteria. Profoundly asocial, he once called himself ‘a bit of a stranger to the human race.’ He also suffered at times from debilitating depression, and was bullied in school for being bookish and fat. Yet he transformed his sense of personal injury to a poetic voice of rigor and flexibility, humor and empathy, and enormous formal range. He was a generous anthologist and editor as well as an essayist, poet, and verse novelist. ‘It was a very great epiphany for me,’ he once said, ‘to realize that poetry is inexhaustible, that I would never get to the end of its reserves.’”

We had mutual friends, among them Alexander Deriev, whose wife was the late Russian poet Regina Derieva, and the poet Dave Mason himself, who is now an Australian poet by choice rather than birth. He had corresponded with Murray, who published some of his poems (presumably in the Australian Quadrant, where Murray was poetry editor) but they never met face to face.

Here’s another treat: if you want to know something about him, you might go to this soundcloud 1985 PEN recording of Joseph Brodsky, Derek Walcott, and Richard Howard in conversation with Murray. I’m still listening to it…

“The body of work that he’s left is just one of the great glories of Australian writing,”said his agent of three decades, Margaret Connolly. “The thought that there will be no more poems and no more essays and no more thoughts from Les – it’s very sad and a great loss.”

“The body of work that he’s left is just one of the great glories of Australian writing,”said his agent of three decades, Margaret Connolly. “The thought that there will be no more poems and no more essays and no more thoughts from Les – it’s very sad and a great loss.”

David Mason, writes: “Murray deserves to be ranked among the best devotional poets—from Donne and Herbert to Eliot and Auden—but his work has an earthiness and irreverence of its own, a tragic sense of human life and a Whitmanesque sympathy for the lives of animals. His wordscapes and landscapes were local, Australian, with everything that distinction signifies—including the transported convict’s sense of justice and the nation’s thoroughly multicultural heritage. His art wasn’t bound by pieties, political or otherwise, because he understood the position of poetry—and of language itself—in relation to reality.”

Faced with the theological question “Why does God not spare the innocent?,” Murray replied in a quatrain that is perhaps one of his best known poems, perhaps because of, rather than despite, its economy of words:

The answer to that is not in

the same world as the question

so you would shrink from me

in terror if I could answer it.

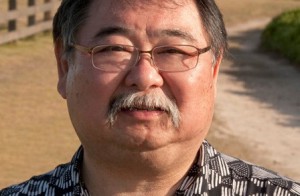

Les Murray, Daniel Weissbort and Alexander Deriev having meal after the Ars Interpres Poetry Festival. Stockholm, 2004.

David notes that the poem, called “The Knockdown Question,” is a minor epigram in the Murray oeuvre, “but it partakes of the same theological experience as Eliot’s Four Quartets. Murray was not always so blunt.”

David Malouf told the ABC that Murray was “utterly unorthodox” and described his work as “undoubtedly the best poems anybody has produced in Australia.”

“He knew that he could be difficult — nobody pretends that he wasn’t — but he was always difficult in an interesting way.”

He told the Paris Review: I’m a dissident author; the deadliest inertia is to conform with your times.”

Poet

Poet