Farewell to John Felstiner, critic, translator, poet: “an exemplary life in literature”

Friday, March 3rd, 2017

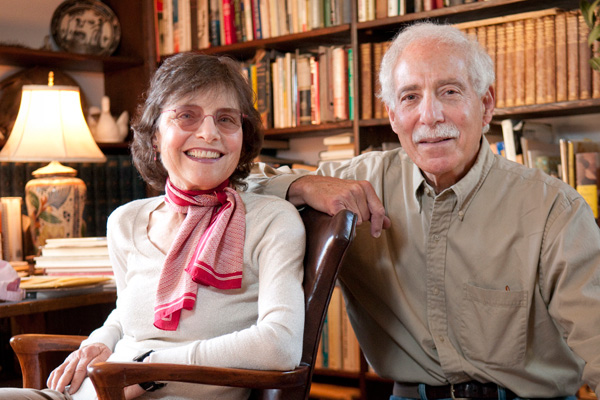

Mary and John Felstiner at their campus home in 2009. (Photo: Linda Cicero)

Literary critic, translator, and poet John Felstiner died last week, on Friday, Feb. 24. He was 80, and had suffered from aphasia for six years. The Stanford professor of English is perhaps best remembered for his book Paul Célan: Poet, Survivor, Jew (Yale, 1997). His translation of Célan’s legendary poem, “Todesfuge,” is widely considered a masterpiece in itself (read more about his translation of the poem here). He is remembered by colleagues for his passion, humor, and fierce intelligence.

Don Share, poet and editor of the nation’s preeminent Poetry magazine, praised “an exemplary life in literature.”

Exemplary. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

“As [poet/translator] Michael Hofmann put it, his book Paul Célan: Poet, Survivor, Jew was ‘of inestimable value to anyone wanting to read Célan with understanding.’ That’s because John didn’t just translate the work, he translated the life – both difficult to narrate, but he succeeded. It should also be remembered that Felsteiner’s scholarly and literary service extended to the likes of work on Henry James, Max Beerbohm, Pablo Neruda, Franz Kafka, and editing collections of nature poems and Jewish-American literature, just to give a sampling.”

He was also known for his book Can Poetry Save the Earth? A Field Guide to Nature Poems (Yale University Press), published in time for Earth Day, April 22, 2009. An NPR interview here; I wrote about the book here. An excerpt:

I’m not a scientist or a policymaker, I’m not a nature writer,” he said, deciding that he must be an environmentalist “for fear of being irrelevant.”

“In fact, environmental urgency trumps everything else,” he said. “I say that with due respect to the horrible tragedies happening all over the world.”

He began to wonder how he could use poetry about nature to reach people, using “the pleasure of poetry to reach their consciousness, and their consciousness to reach their conscience.”

“What’s the transition from consciousness to conscience—so that you will never drop an empty beer can in a bush?” he said.

The book that emerged from his labors—including six years teaching the Introduction to the Humanities course titled Literature into Life—took nine years to write.

At that time, I had interviewed John over the phone – he was at the couples’ home in the Santa Cruz mountains. But I interviewed both Mary and John face to face when I interviewed John and his wife, Mary Felstiner, a visiting professor in history, about a course they were teaching a course on what they called “creative resistance” during the Holocaust. They had given a talk at Stanford Hillel’s Koret Pavilion on their research.

What I wrote:

“People are so focused on the tragedy of the Holocaust – or if they think of resistance, it’s of armed resistance – that it’s so easy for humanities and arts and letters to get forgotten. Yet that’s what makes us human beings,” said John Felstiner their campus home.

The team is well positioned to map out this new branch of scholarship: He is the lauded translator and biographer of poet Paul Célan (1920-70). She is the acclaimed biographer of Charlotte Salomon (1917-43) in To Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era.

The common feature of creative resistance, said Mary Felstiner, “is that pushing into the future, that sense that we need to mark this moment because there must be a future out there that will look back on us.”

The common feature of creative resistance, said Mary Felstiner, “is that pushing into the future, that sense that we need to mark this moment because there must be a future out there that will look back on us.”

The Felstiners’ investigations show that an explosion of drawings, paintings, music, writing, even graffiti was “pervasive all over Europe, all of the time, in unthinkable conditions.” …

For Stanford art and art history Associate Professor Jody Maxmin, the Felstiners’ April presentation offered “a clarity and simplicity that reminds me of what drove me to art in the first place.”

Perhaps that’s one reason why an unexpected sense of exaltation accompanied the standing-room-only event: “The last thing one wants to do is take joy in the Holocaust, but there is an elation to art,” said John.

Felstiner was born in Mount Vernon, New York, on July 5, 1936, and grew up in New York and New England. He graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, A.B. (magna cum laude), 1958, and Harvard University, Ph.D., 1965.

From 1958 to 1961, he served on the U.S.S. Forrestal, in the Mediterranean. He arrived at Stanford in 1965 as a professor of English, retiring in 2009.

He was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship for Humanities. Paul Célan: Poet, Survivor, Jew was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism. His Selected Poems and Prose of Paul Celan was published in 2001. See more of his books here.

He was three times a fellow at Stanford Humanities Center; a Fulbright professor at University of Chile (1967–68); visiting professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem (1974–75); and visiting professor of Comparative Literature and English at Yale University (1990, 2002).

His collection of Célan’s manuscripts and letters, along with Felstiner’s own translation archive, are at the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

He continued to swim every day until his final weeks, despite his illness. He went on expeditions with those around him, continued to enjoy music and poetry, and looked forward to visits from his children and grandchildren. From my own occasional meetings with him, I know losing language and cognition frustrated him enormously, and I was moved to hear that he struggled against it to the last.

He is survived by his wife Mary, his two children: Sarah and Alek, and also two grandchildren.