“Mark Twain, but with a harder edge”: new film on Flannery O’Connor – and here’s the trailer!

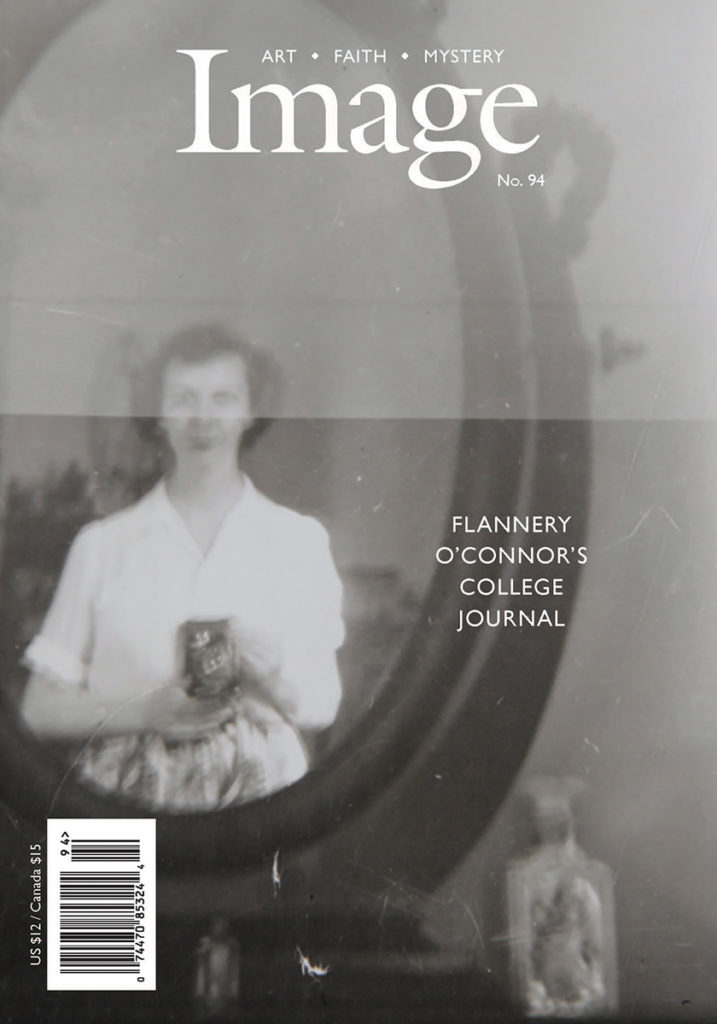

Friday, September 27th, 2019Among the highlights during my brief Chicago visit last week was the first-ever full screening for a general audience of Flannery: The Storied Life of the Writer from Georgia, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The film, directed by Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco, includes never-before-seen archival footage and photographs. Mary Steenburgen narrates, with interviews from Alice Walker, Tobias Wolff, Tommy Lee Jones, Mary Karr, Alice McDermott, Conan O’Brien, Mary Gordon, and people from O’Connor’s life. (The film includes “motion graphics,” rather than “dramatic reenactments,” in keeping with the requirements of the O’Connor Trust.)

“Most literary biopics and most documentaries about writers fail in my opinion because they tend to exclude or at least minimize the writing when of course the writing itself is the key element that defines why we care about the writer,” said film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, in remarks before the screening. He was critic for the Chicago Reader from 1987 to 2008, and author of a number of books on films. “There’s an analogous problem for me in most films that feature jazz, where it’s felt that audiences are too restless to sit still for uninterrupted writing.”

Then he cited Wendy Lesser, writing in Bookforum: “Flannery O’Connor is like Mark Twain, but with a harder edge. Both the pathos and the ludicrousness of the life she perceives and creates are always present to her, and which one will win out depends on how wrathful she feels her God to be at any given time.”

“Ignorance is by no means her only target. Knowingness, of a highly educated and smug sort, also comes under fire, especially in the later stories that are more visibly self-mocking.”

But the final word in his remarks was from O’Connor herself, in her preface to Wise Blood: “Does one’s integrity ever lie in what he is not able to do? I think that usually it does, for free will does not mean one will, but many wills conflicting in one man. Freedom cannot be conceived simply. It is a mystery and one which a novel, even a comic novel, can only be asked to deepen.”

George Saunders, author of Lincoln in the Bardo, called it “a beautiful and important film about one of our great American artists.” The screening at Loyola’s Damen Cinema was part of the “Catholic Imagination” conference, launched by Dana Gioia in 2015.

From the January 19, 1944 page in the journal:

From the January 19, 1944 page in the journal: