Michael Hoffman: “I have mostly ended up translating dead people. They are more appreciative.”

Sunday, May 6th, 2018

Danke, Herr Hamburger.

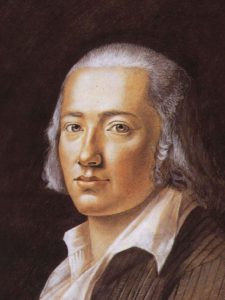

My work involves reading poets, essayists, novelists from all over the world, so every day I have occasion to consider how very much I owe to translators – for example, Michael Hamburger‘s translations of Friedrich Hölderlin. I know, I know … Hölderlin is impossible to translate, but the only alternative to reading translations is to give oneself over to learning every European language, and a few Asian ones, or else slide into a sort of literary parochialism.

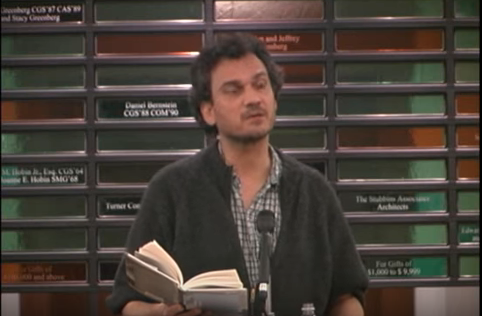

I haven’t worked with enough German to run across Michael Hoffman, “arguably the world’s most influential translator of German into English, who can single-handedly revive an author’s reputation, as he did with Hans Fallada.” That’s according to Philip Oltermann, writing an article some time ago in The Guardian. The provocative title “English is basically a trap. It’s almost a language for spies.”

Hoffman’s reviews have a reputation for savagery, but he sees it as a form of pruning: “I have a sense of the enterprise being ecological,” he says. “There is so much excessive praise and excessive interest in the books world, and it’s all too focused on too few people. If you cut things down to scale, you do something good.”

A few excerpts:

A reputation for savagery: but “all shy eyes and nervous hands.”

… one of the 58-year-old’s trademark masterclasses in literary evisceration: a forensic demolition job on Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North in the London Review of Books, in which Hofmann had described the 2014 Man Booker winner as “ingratiating”, “gassy” and “lacking the basic dignity of prose”.

It wasn’t Hofmann’s first dismantling, and not even the most vicious. In another LRB review, he had written after reading Martin Amis’s latest, elsewhere feted as a glorious return to form: “I read The Zone of Interest straight through twice from beginning to end and it feels like I’ve read nothing at all.”

His most eminent literary compatriot, Nobel-winner Günter Grass, came under the guillotine in 2007 in this publication: Grass’s confessional memoir Peeling the Onion, he wrote, contained “two pages of failed writing that should be put in a textbook, and quarried for their multiple instances of bad faith”.

Like a Soho drunk stumbling into the National Portrait Gallery in search of a good scrap, Hofmann has battered posthumous reputations with the same glee as those of the living. “Stefan Zweig just tastes fake,” he wrote in another review, dismissing the widely revered Viennese man of letters as the “Pepsi of Austrian writing”.

The real Hofmann doesn’t quite fit with the cartoonish picture of a lit-crit Johnny Fartpants. As he sits in an incongruously rowdy Hamburg bar, all shy eyes and nervous hands, one is reminded that he is also a poet and translator: a humble servant of words, not just their sneering judge.

***

Translators need “an active sense of mischief”

One of his guiding principles for translating, he says, is to avoid the obvious word, even if it is the literal equivalent of the original. When the opening page of a [Joseph] Roth novel contained the word Baracke, he insisted on going with “tenement” rather than “barracks”. In the second paragraph of Hofmann’s version of Metamorphosis, Gregor Samsa doesn’t ask “What happened to me?” (Was ist mit mir geschehen?), but “What’s the matter with me?”. He liked the phrase, he says, because it sounds like someone having trouble getting up after a heavy night.

“Nobody will notice, but you have taken a step back from the original. You have given yourself a little bit of self-esteem, a little bit of originality, a little bit of boldness. Then the whole thing will appear automotive: look, it’s running on English rather than limping after the German.”

Without an active sense of mischief, he says, translators can easily become bitter people. “Nobody sees what you are doing, and the minute you do something, people cry ‘Mistake, mistake!’. If done in that way, it feels almost parasitic upon literature. You can begin to understand fussy authors such as Kundera, who minimise the space of translators. That’s partly why I have mostly ended up translating dead people. They are more appreciative.”

Read the whole thing here.