Remarkable spirit: remembering scholar, author, feminist Marilyn Yalom (1932-2019)

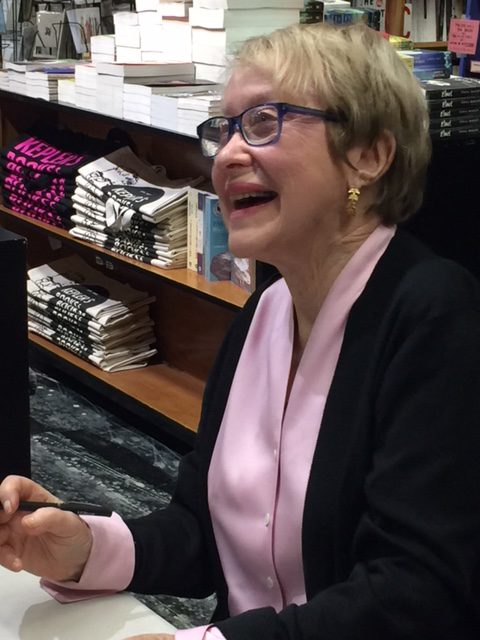

Wednesday, November 20th, 2019Marilyn Yalom, a popular French scholar and author, a founder of feminist studies at Stanford, and beloved wife of the celebrated author and psychiatrist Irv Yalom, died this morning of myeloma. She was 87.

Her illness was swift, but long enough for friends to express their love and appreciation. On September 1, a surprise party was held at her home by women writers who were part of her Bay Area women writers’ salon. A book of letters was presented to her then from the salonnières.

Marie-Pierre Ulloa, a lecturer in Stanford’s French and Italian Department, also collected letters for a book, this time from the Stanford community. The fate of the book, which was presented to Marilyn in unfinished form a few days ago, remains up in the air, but Marie-Pierre is allowing me to publish my contribution here, as a sort of eulogy.

Dearest Marilyn,

You don’t remember our first meeting, so I’ll remind you: in 1983, I interviewed you to discuss your anthology, Women Writers of the West Coast.

The setting was your charming home on Matadero Avenue, though I have few memories of the house that would eventually become so familiar to me. I disappeared from your life then, and returned nearly a quarter century later, when the legendary Diane Middlebrook died in 2007, and I somewhat timidly joined the Bay Area women writers salon that had become your own endeavor, extending the note that your closest friend had sounded.

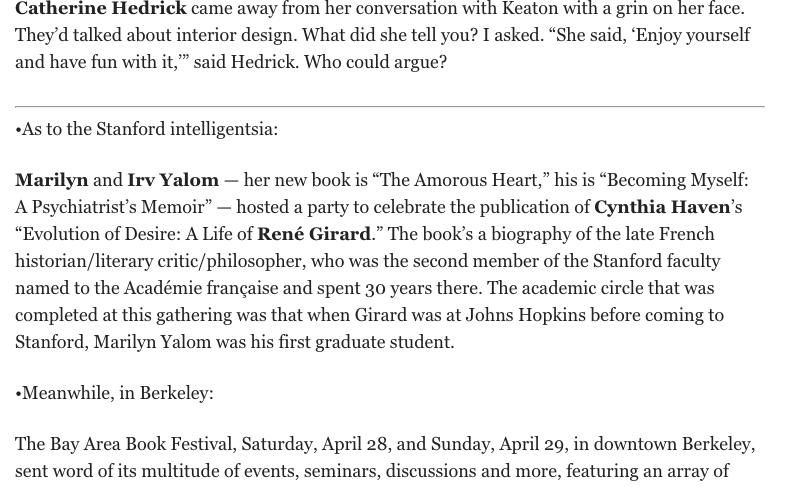

Working on Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, I came to know your academic beginnings as the French theorist’s first graduate student: a young woman in a high-powered program at Johns Hopkins, arriving in 1957. “The dedication to our work was, for me, beyond anything I had experienced at Wellesley or Columbia or the Sorbonne,” you told me. “We were true believers. The life of Johns Hopkins was the life of a scholar.” You received your doctorate with distinction. We would talk meet again in the redwood and stone home nestled among the oaks and tall pines – sometimes taking tea in Wedgwood cups, among the hundreds of books, the Balinese masks, the framed art photographs, and a serene Buddha; at other times, sharing a glass of your son Reid’s Cabernet at night, as we waited for your husband Irv to return home from a meeting.

Working on Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, I came to know your academic beginnings as the French theorist’s first graduate student: a young woman in a high-powered program at Johns Hopkins, arriving in 1957. “The dedication to our work was, for me, beyond anything I had experienced at Wellesley or Columbia or the Sorbonne,” you told me. “We were true believers. The life of Johns Hopkins was the life of a scholar.” You received your doctorate with distinction. We would talk meet again in the redwood and stone home nestled among the oaks and tall pines – sometimes taking tea in Wedgwood cups, among the hundreds of books, the Balinese masks, the framed art photographs, and a serene Buddha; at other times, sharing a glass of your son Reid’s Cabernet at night, as we waited for your husband Irv to return home from a meeting.

We spoke about your years as a harried graduate student and mother of several children, living in the housing assigned to young psychiatrists in residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital. In that era of more limited expectations for women, perhaps few anticipated that you would become such a popular and acclaimed author in your own right, with a shelf of books to your credit. Our friendship ripened during the years you published How the French Invented Love: Nine Hundred Years of Passion and Romance (HarperCollins, 2012) and then The Amorous Heart in 2018, a few months before my own book. I attended your public events for it, at Kepler’s, at the Stanford Humanities Center, and wrote about them (here and here).

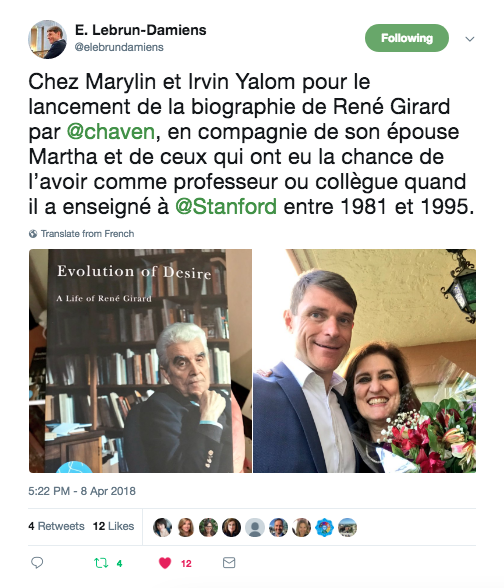

That was the public part. But then there was the unseen part, the salon part: encouraging women to write; guiding their publishing decisions; coaching them to absorb your own authorial dignity and tact, though few of us mastered those lessons as well as you had. You even persuaded a few of us to get top-notch author’s photos from another friend, the notable photographer Margo Davis. At each gathering on Matadero or at your apartment in the City, the salonnières would describe our most recent triumphs and challenges, and one of two of us would present our newly published books. You did more: I remember the launch party for Evolution of Desire, with cases of fine French wine, guests from around the world, and armloads of orchids from my garden – and a special guest, the French consul Emmanuel Lebrun-Damiens. You encouraged us to keep writing, keep writing, keep writing, as you did.

That was the public part. But then there was the unseen part, the salon part: encouraging women to write; guiding their publishing decisions; coaching them to absorb your own authorial dignity and tact, though few of us mastered those lessons as well as you had. You even persuaded a few of us to get top-notch author’s photos from another friend, the notable photographer Margo Davis. At each gathering on Matadero or at your apartment in the City, the salonnières would describe our most recent triumphs and challenges, and one of two of us would present our newly published books. You did more: I remember the launch party for Evolution of Desire, with cases of fine French wine, guests from around the world, and armloads of orchids from my garden – and a special guest, the French consul Emmanuel Lebrun-Damiens. You encouraged us to keep writing, keep writing, keep writing, as you did.

And as you do still. Even now, you are writing a book with Irv, jointly documenting this last year of your journey together, a story that began when you were teenagers in Washington D.C. In our most recent phone call a week or two ago, you assured me that illness had not stopped your work. You are still working on the manuscript, together.

I describe all this because it is an inspiring model for all of us. Your lifetime’s effort will live through us, and touch so many others who will never have a chance to meet you. I want it to be remembered, beyond this year and beyond Stanford. There is no one like you, and no one will take your place. Our gratitude to you is deep, and our love deeper still.

Postscript: One thing I should have written, and didn’t: She was a class act, a woman of extraordinary poise, graciousness, and charm.