They scatter the dark: three Polish poets in Berkeley

Thursday, April 7th, 2016

If you noticed a slight shimmer in the firmament last week, I know the reason. There was a superb display of talent at Berkeley’s “Scattering the Dark: Celebrating the New Generation of Female Polish Poets,” featuring Krystyna Dąbrowska, Izabela (Filipiak) Morska, and Julia Fiedorczuk. Who better to moderate the reading and discussion than Pulitzer prizewinning Robert Hass, former U.S. poet laureate and the preeminent translator of Czesław Miłosz? He hailed the “three amazingly adventurous poets” and was delighted to extend the “intermittent conversation” between English and Polish poetry.

Bob asked the inevitable question of the three: How did they live in the shadow of the poetry of the 20th century giants and the “huge moral trauma it responded to?” He was thinking of course of Miłosz, Wisława Szymborska, Zbigniew Herbert,Tadeusz Różewicz, Julia Hartwig.

Krystyna added the lesser known (in the West) Miron Białoszewski to the list, then dismissed the issue: “For my generation, it’s not such a problem. The younger poets are looking for different sources of inspiration,” she said. They also have new historical sources for trauma: the reactionary turn in the country that was once hailed as the champion of post-Soviet democracy and recovery. Her own inspiration tends to be enigmatic, imaginative, and personal, such as this one in the poem “Travel Agency”:

I am a travel agency for the dead,

I book them flights to the dreams of the living. …

She roundly criticized critic Andrzej Franaszek‘s recent 2-page editorial in a major Polish newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, which claimed that people don’t read poetry anymore and addressed the reasons why. He blamed hermetic trends and experiments in language poetry – John Ashbery has been a powerful influence on recent generations of poets – and called for a new poetry based on experience. (I wondered if Franaszek’s role as Miłosz’s biographer had a hand in his p.o.v.: “Blessed be classicism and let us hope it did not pass away forever,” the Polish poet had said.)

Julia was also angry at Franaszek’s editorial, for other reasons: not a single living woman poet was named. She published a spirited reply, suggesting that if Franaszek did not like today’s poetry, perhaps he should not review it.

Izabela said the fictional alter ego “Madame Intuita” is her response to the generation of giants, with its homage to Herbert’s “Mr. Cogito.” Like Miłosz himself, she herself had been an immigrant, though one who had lived in a refugee center and shared utensils with other displaced people:

My whole life’s like learning a second language –

so many immigrant sacrifices but in the end

I can’t get rid of this accent, recognized

everywhere to my annoyance.

And I’d been feeling almost assimilated!

All that effort, and for what?

However, she pointed out today’s poets face hurdles that the yesterday’s giants never knew. To wit: the “acrobatics” to get into the publications were something Miłosz and Herbert never faced. She described the hardscrabble life of the writer, the uncertain income, the rejection letters and the silence that is worse than rebuffs. “I feel like I’m on a trapeze and doing somersaults and hoping I catch the next trapeze,” she said. Such a precarious life is “strange at about thirty, more strange at 40, and kind of odd at 50.” But in that sense, the life of the writer is most universal.

“Failure is the key human experience,” said Izabela, who had been a visiting scholar at Berkeley from 2003-2005. It’s a universal one, because “none of us arrive at the destination,” the imagined empyrean we never reach. She remembered George Orwell, and said this realization is why “poverty became his topic.” I believe that is one reason why Orwell will last.

Failure is the key human experience, and her words were all the more powerful for being spoken in the Bay Area and Silicon Valley, a place where success is both addiction and the drug itself. We trumpet our successes on Facebook, perpetually shine our C.V.’s, and forge ahead in our determined effort to “brand” ourselves and market ourselves. We risk replacing the face with the mask we have created.

Failure is the key human experience, and her words were all the more powerful for being spoken in the Bay Area and Silicon Valley, a place where success is both addiction and the drug itself. We trumpet our successes on Facebook, perpetually shine our C.V.’s, and forge ahead in our determined effort to “brand” ourselves and market ourselves. We risk replacing the face with the mask we have created.

It was a magical evening, that ended at Chez Panisse, Miłosz’s favorite haunt. I suspect Miłosz was the presiding spirit of the evening. Berkeley was, after all, his home for forty years, and where he trained a generation of translators.

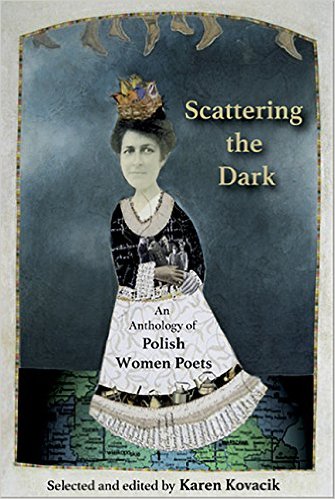

Most of the poems that were read came from a new anthology Scattering the Dark. But one, inspired by Miłosz, was not. I cannot do better for my tribute today than include a poem indirectly inspired by him. The one I wanted to use, “Psalm 31,” is under consideration for publication (we’ll send a link to it when it is), but she sent “Psalm 2” as a replacement. After all, said Julia: “the whole cycle rhythmically and poetically alludes to Miłosz’s translation of the Hebrew Psalms.”

Psalm II

for M. M.

some poems cannot be written any longer.

some could not be written until now.

nighttime despair because of the children, drowned

children, hanged children, burned

children, massacred children, toys of children

in the plane wreck, because motherhood

is a life sentence, while despair seeks ornaments

and pleasing shapes, so as to dress up in them,

take shelter in them, be protected;

so best be quiet, I’m saying, so I’m saying: none

of your bones is going to be broken, let’s say, “you shall want for nothing,” let’s say,

“you shall want for nothing,” let’s say,

“a tree will be planted by the flowing waters” –

(Translated by Bill Johnston)

Krystyna Dabrowska, Izabela Morska, Julia Fiedorczuk. Three Polish poets plus Bob Hass. (Photo: Halina Zdrzalka)