“Karski & the Lords of Humanity”: The story of the man who tried to stop the Holocaust

Thursday, April 21st, 2016

He tried to tell us.

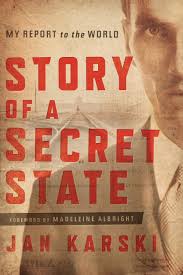

I had a lot of work to plough through tonight, but duty and interest called me for a brief foray out to the Stanford campus – specifically, to the new McMurtry Building to see the 2015 film, Karski & the Lords of Humanity, sponsored by the Hoover Institution Archives and the Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies. It was showing for free. The theater was only a third full – and it’s a shame. The name Jan Karski (1914-2000) should be a household word, and it’s not.

This short movie isn’t perfect (the drawings are overused to portray action, and it begin to grate), but the film serves as a good introduction to a man still too little known.

The brief New York Times review last fall only begins to describe it:

One of the many interviewees in “Shoah,” Claude Lanzmann’s definitive nine-and-a-half-hour 1985 documentary about the Holocaust, was Jan Karski, a Pole whose undercover missions in World War II gave early information to the Allies about the extermination of Polish Jews. Slawomir Grunberg’s stately documentary “Karski & the Lords of Humanity” focuses exclusively on Karski’s courageous adventures in intrigue and espionage.

The handsome, dapper, erudite and multilingual Karski (1914-2000), who was blessed with a photographic memory and educated as a diplomat before serving in the military, was an ideal candidate for the Resistance. Often working for the Polish government in exile in London, he conducted many missions, among them a trip incognito to the Warsaw Ghetto, illustrated here with utterly harrowing photographs. Karski presented his eyewitness account in person to officials in Britain and, eventually, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His exploits — surviving brutal torture by the Gestapo; a daring hospital escape; smuggling microfilm; using medical mean to disguise his accent — are fleshed out with vivid animated sequences, while experts offer testimony.

My Hoover Archives friends recall meeting the tall, distinguished Pole from Georgetown University during his visits. Little known fact: the Karski papers are at the Hoover Archives. Anyone can see them, with a request.