Good grief: on death, mourning, and unpredictability

Tuesday, July 12th, 2022

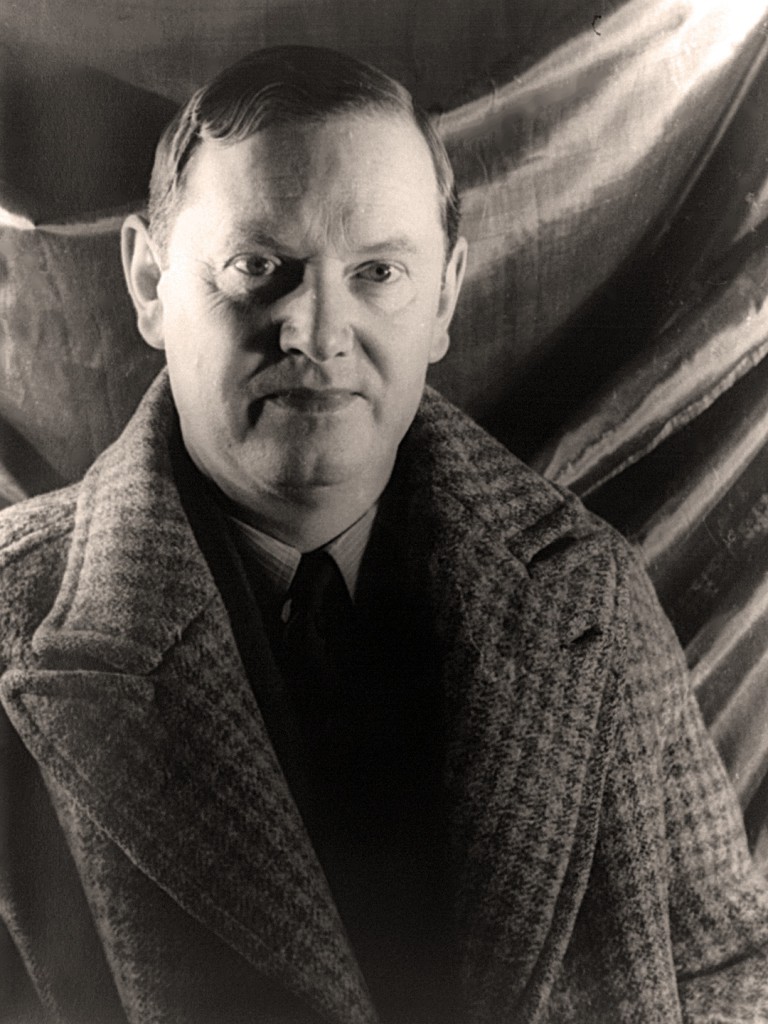

Grief is painful. We all know that. But Is there a “good grief”? Eminent essayist and man of letters Joseph Epstein discusses grief, theoretically and from personal experience, including the devastating loss of his son by opioid overdose, as well as departed relatives and friends in his essay, “Good Grief” in Commentary. Like him, I haven’t experienced the legendary “five states of grief,” which I see as an attempt to organize and manage grief, which is by its nature tormenting, chaotic, unpredictable.

Socrates argued that we should keep death foremost in our minds, and that our inevitable deaths will goad us to live better lives. “But no one has told us how to deal with the deaths of those we love or found important to our own lives. Or at least no one has done so convincingly,” he writes. A few excerpts:

Like death itself, grief is too manifold; it comes in too many forms to be satisfactorily captured by philosophy or psychology. How does one grieve a slow death by, say, cancer, ALS, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s; a quick death by heart attack, stroke, choking on food, car accident; death at the hands of a criminal, which in our day is often a random death; death at a person’s own hands by suicide; death in old age, middle age, childhood; death in war; yes, death by medicine tragically misapplied. Grief can take the form of anger, even rage, deep sorrow, confusion, relief; it can be long-lived, short-term, almost but never quite successfully avoided. The nature of grief is quite as highly variegated as its causes.

Grief, like the devil, is in the details. I have a good friend whose son committed suicide at age 41. A young man devoted to good works, he ended his life working for an international agency in central Africa. At his suicide, the only note he left was about what he called “this event” having nothing to do with his work. To this day, then, his father and other relatives do not know the reason for his taking his own life, which adds puzzlement to my friend’s grief, a puzzlement perhaps never to be solved.

***

But no one has told us how to deal with the deaths of those we love or found important to our own lives. Or at least no one has done so convincingly. The best-known attempt has been that of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a Swiss psychiatrist, in her 1969 book On Death and Dying and in her later book, written with David Kessler, On Grief and Grieving (2005). Kübler-Ross set out a five-stage model for grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. Yet in my own experience of grieving, I went through none of these stages, which leads me to believe there is more to it than is dreamt of in any psychology yet devised.

Or, one might add, in any philosophy. In Grief, Michael Cholbi, who holds the chair in philosophy at the University of Edinburgh, informs us that philosophy has never taken up the subject of grieving in an earnest way. He attempts to make the positive case for grief: “The good in grief, I propose, is self-knowledge.” Cholbi defines grief as “an emotionally driven process of attention whose object is the relationship transformed by the death of another in whom one has invested one’s practical identity.” As for the term “practical identity,” it was coined by the American philosopher Christine Korsgaard, who writes that it is “a description under which you value yourself, a description under which you find your life to be worth living and your actions to be worth undertaking.” The value of grief, then, according to Cholbi, is that “it brings the vulnerability, and ultimate contingencies of our practical identities into stark relief” and, ideally, “culminates in our knowing better what we are doing with our lives.”

***

More recently Midge Decter, a dear friend, died at age 94. One cannot be shocked, or even surprised, by the death of someone who has attained her nineties, yet one can nonetheless feel the subtraction created by her absence. I loved to invoke her intelligent laughter, and it would never occur to me to attempt in any way to dupe her full-court-press savvy. One of the sad things about growing older is that one runs out of people to admire, as I admired Midge, for her good sense, her wit, her intellectual courage.

***

Cholbi, while allowing that grief is “perhaps the greatest stressor in life,” finds it neither a form of madness nor worthy of being medicalized, grief being neither a disease nor a disorder. He finds it instead part of “the human predicament,” a part that eludes even philosophical understanding. “We can grieve smarter,” he writes. “But ultimately, we cannot outsmart grief. Nor should we want to.” We do not ultimately recover from grief; if lucky, we merely at best are able to adjust to it.

Read the whole thing here.