What happens when Joshua Cohen meets Harold Bloom? “The function of criticism now is to abandon politics.”

Thursday, August 16th, 2018

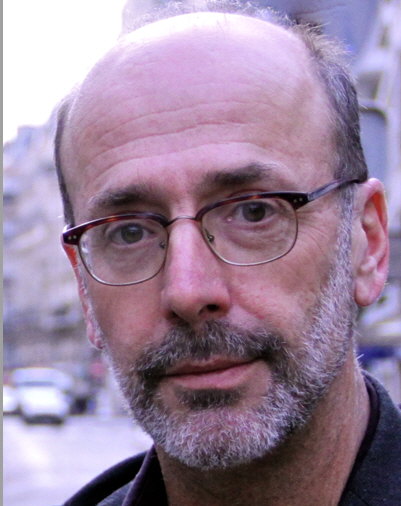

“Rusticating mentor.”

Novelist Joshua Cohen took a train to Connecticut to interview legendary litcritic Harold Bloom: “As my train dragged its way through Bloom’s native Bronx — and continued upriver through the rising heat of Westchester and into that great humid smog-cloud that covers all of Connecticut beyond the stockbroker coast — I had the unsettling feeling that I’d been cast in some straight-to-YouTube adaptation of one those classic scenes of literary visitation, wherein a young bookish type makes a pilgrimage from the stifling city to pay homage to a rusticating mentor.”

Here’s how the interview began:

Joshua Cohen: It’s an honor to meet you, Harold. You’re being very generous and kind and —

Harold Bloom: Okay, okay, enough. Sit down.

Cohen: I’m sitting.

“Young bookish type.”

Bloom: I was thinking all day, what questions will you ask? You’re recording?

Cohen: I am. I’m recording on my phone — and we might as well begin with that, because one of the things I wanted to speak with you about was memory. Everyone calls this “a phone,” but my generation in particular considers it as something more like an external brain. It stores our sounds, our images, our books. I need this extra storage space, this extra memory, to compensate for my own. But, famously, you don’t. You remember everything.

Bloom: Our backgrounds are similar, Joshua, but remember: We’ve lived half a century apart. So I can’t speak of technology. But my memory is a freak — this is true. I had it from when I was a little one, growing up in the Bronx, and going to the Sholem Aleichem schools. My first language was Yiddish. There was no English in our house, or even really in our part of the Bronx.

Puzzling.

It continued:

Bloom: Kafka is the ultimate Jewish puzzle.

Cohen : I’ve always been troubled by his story “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse-Folk” — which was the last story he ever wrote. And it famously ends with a line that says, in essence, to be forgotten is to be redeemed. I know you’ve written about this line: in your interpretation, it’s not a melancholy statement. Because though the singer might be forgotten, her song will be remembered: in fact, the more the song will be remembered, the more the singer can be forgotten, because her art remains secure. I agree with your interpretation, though I’d point out that when I reread this story last year, I found myself baffled and touched by the faith that Kafka has in “the community”: the “mouse-folk” who will preserve Josephine’s song. What do you make of Kafka’s belief in a “community” that doesn’t just preserve its culture, but incarnates it?

Bloom: It makes me unhappy. Whatever Jewish culture is, or is not, it will vanish with the last Jew. And who knows when that will be?

It ended:

Cohen: And what about criticism — what is its relationship to the preservation, or survival, of our culture? If criticism becomes solely concerned with the political — the here and now — will there be no world-to-come?

Bloom: The function of criticism now is to abandon politics. Whatever the voice that is great in us is, it relates to perception and knowledge.

That’s the preview. Read the whole thing at the Los Angeles Review of Books here.

He was primarily a historical and political novelist. He published four novels, one set in the history of the Holocaust and the state of Israel; (

He was primarily a historical and political novelist. He published four novels, one set in the history of the Holocaust and the state of Israel; (