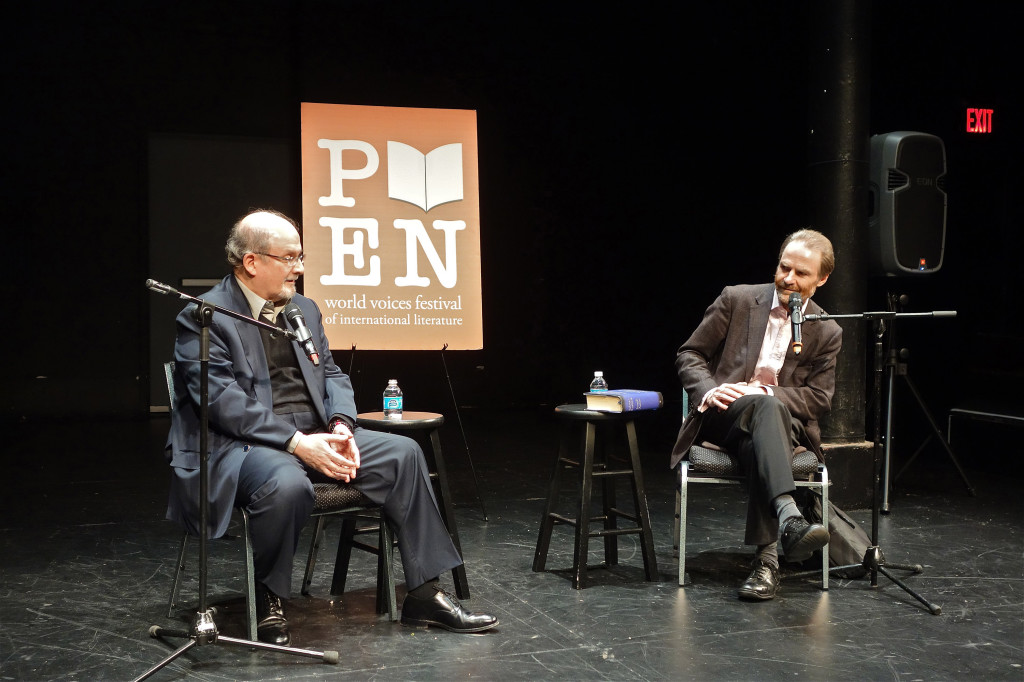

Would people defend him today? He thinks not. With Timothy Garton Ash last year. (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

Charlie Hebdo has announced that they will publish no more cartoons featuring Mohammed, although every other religion and public figure will continue to be fair game. In other words, the terrorists have won. “We have drawn Mohammed to defend the principle that one can draw whatever they want… We’ve done our job,” said Laurent “Riss” Sourisseau, Charlie Hebdo’s editor-in-chief.

It’s hard to be nostalgic about a fatwa, but Sir Salman Rushdie‘s recent comments in The Telegraph remind us that his Valentine’s Day card from the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 were the good old days. Leading figures from around the world linked arms to express solidarity with him, and to protest any encroachment on freedom of speech. Susan Sontag, Norman Mailer, Joseph Brodsky, Christopher Hitchens, Seamus Heaney, and others stood for Rushdie. There was no backing down. And today?

Said Rushdie, “We are living in the darkest time I have ever known.” The author of the condemned Satanic Verses, told France’s L’Express. “I’ve since had the feeling that, if the attacks against Satanic Verses had taken place today, these people would not have defended me, and would have used the same arguments against me, accusing me of insulting an ethnic and cultural minority.”

Thank you, Christopher.

In particular, Rushdie said he was dismayed by the protests that followed a decision by the American branch of the PEN writers’ association to award a prize for courage to Charlie Hebdo after a dozen of its staff were massacred in January. More than 200 writers, including Michael Ondaatje, Teju Cole, Peter Carey, and Junot Díaz, signed a letter objecting to PEN rewarding the satirical magazine for publishing “material that intensifies the anti-Islamic, anti-Maghreb, anti-Arab sentiments already prevalent in the Western world.”

“It seems we have learnt the wrong lessons,” Rushdie told L’Express. “Instead of realizing that we need to oppose these attacks on freedom of expression, we thought that we need to placate them with compromise and renunciation.” Cole explained to him that his case was different – 1989 protesters defended Rushdie against charges of blasphemy; Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons, he argued, were an expression of Islamophobia.

Rushdie thinks it’s a case of political correctness gone wild. “It’s exactly the same thing,” he said. “I’ve since had the feeling that, if the attacks against The Satanic Verses had taken place today, these people would not have defended me, and would have used the same arguments against me, accusing me of insulting an ethnic and cultural minority.” (To be clear, I find Charlie Hebdo cartoons tasteless and not very funny. That’s not the point.)

Let’s remember Sontag, president of PEN, in that 1989 moment. Hitchens wrote: “Susan Sontag was absolutely superb. She stood up proudly where everyone could see her and denounced the hirelings of the Ayatollah. She nagged everybody on her mailing list and shamed them, if they needed to be shamed, into either signing or showing up. ‘A bit of civic fortitude,’ as she put it in that gravelly voice that she could summon so well, ‘is what is required here.’ Cowardice is horribly infectious, but in that abysmal week she showed that courage can be infectious, too. I loved her. This may sound sentimental, but when she got Rushdie on the phone—not an easy thing to do once he had vanished into the netherworld of ultraprotection—she chuckled: ‘Salman! It’s like being in love! I think of you night and day: all the time!’ Against the riot of hatred and cruelty and rage that had been conjured into existence by a verminous religious fanatic, this very manner of expression seemed an antidote: a humanist love plainly expressed against those whose love was only for death.”

Thank you, Susan.

Sontag and Hitchens were famous people, of course, who lived in high-rise apartments and could go into hiding, as Rushdie did. But a lot of other people put their lives on the line. Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses, was stabbed to death on the campus where he taught, the Italian translator Ettore Capriolo was knifed in his Milan apartment, and in Oslo, William Nygaard, the novel’s Norwegian publisher, was shot three times in the back and left for dead.

Others at risk included bookstore owners, bookstore managers, and the people who worked for them. So let me take a few moments to recall the heroism of one of them, Andy Ross, owner of Cody’s Books in Berkeley, which was bombed in the middle of the night two weeks after the fatwa was announced. On his own blog (he is now a literary agent) he wrote:

I spoke of the fire bombing that occurred at 2 AM. More troubling was that as we were cleaning up in the morning, an undetonated pipe bomb was found rolling around the floor near the poetry section. Apparently it had been thrown through the window at the same time as the fire bomb. Had the pipe bomb exploded, it would have killed everyone in the store. The building was quickly evacuated. … As I walked outside, I was met with a phalanx of newsmen. Literally hundreds. Normally I was a shameless panderer for media publicity. At this point I had no desire to speak. And I knew reflexively that public pronouncements under the circumstances were probably imprudent. …

Cody’s in 2006. (Photo: Creative Commons/Pretzelpaws)

One-time heroism wasn’t enough. How were they to react to the attack? Would they continue selling the book? Would they put it at the front of the store, or hide it somewhere towards the back? Or would it, like 1950s pornography, be offered by request only, in a brown paper bag?

I stood and told the staff that we had a hard decision to make. We needed to decide whether to keep carrying Satanic Verses and risk our lives for what we believed in. Or to take a more cautious approach and compromise our values. So we took a vote. The staff voted unanimously to keep carrying the book. Tears still come to my eyes when I think of this. It was the defining moment in my 35 years of bookselling. It was the moment when I realized that bookselling was a dangerous and subversive vocation. Because ideas are powerful weapons. It was also the moment that I realized in a very concrete way that what I had told Susan Sontag was truer and more prophetic than anything I could have then imagined. I felt just a tad anxious about carrying that book. I worried about the consequences. I didn’t particularly feel comfortable about being a hero and putting other people’s lives in danger. I didn’t know at that moment whether this was an act of courage or foolhardiness.

But from the clarity of hindsight, I would have to say it was the proudest day of my life.

The story wasn’t over. Rushdie visits the Bay Area regularly (I wrote about his visit to Kepler’s here). And even while in official hiding, he insisted on calling on Cody’s several years later (Berkeley rents finally did what bombs could not, and the valiant bookstore closed its doors in 2008). Ross recalls Rushdie’s appearance at Cody’s:

We were told that we could not announce the visit until 15 minutes before he arrived. It was a very emotional meeting. Many tears were shed, and we were touched by his decision to visit us. We showed him the book case that had been charred by the fire bomb. We also showed him the hole in the sheetrock above the information desk that had been created when the pipe bomb was detonated. One of the Cody’s staff, with characteristic irreverence, had written with a marker next to the damaged sheet rock: “Salman Rushdie Memorial Hole”. Salman shrugged his shoulders and said with his wonderful self-deprecating humor, “well, you know some people get statues – and others get holes.”

Read the whole thing here.