In May 1933, a Stanford University Press sales manager was arrested for the murder of his wife at their campus home on Salvatierra Street.

Was it murder or accident? Placid Palo Alto was embroiled in a sensationalized scandal that endured for more than three years. After conviction, appeals and retrials, David Lamson was finally acquitted.

Young Janet (Courtesy Melissa Winters)

One of the unlikelier outcomes of the notorious case: three distinguished novels by Stanford poet Janet Lewis, focusing on historical trials that had been swayed by circumstantial evidence. The most famous was The Wife of Martin Guerre (1941), which eventually became the subject of an opera, a play, several musicals and a film. Atlantic Monthly called it “one of the most significant short novels in English.”

The book will be the focus of the second “Another Look” book club event at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, Feb. 20, at the Stanford Humanities Center’s Levinthal Room. The event will be moderated by English Professor Kenneth Fields, who was a friend of the late Janet Lewis (1899-1998) and her husband, renowned poet-critic and Stanford professor Yvor Winters (1900-68).

Fields will be joined by acclaimed novelist Tobias Wolff and award-winning Irish poet Eavan Boland, both professors of English. An audience discussion will follow. The community event is free and open to the public, but seating is limited and available on a first-come basis.

Winters’ role in the Lamson case was legendary: Outraged at the injustice, he actively campaigned for Lamson’s acquittal and helped prepare the defense brief. With a colleague, Winters provided a cogent 103-page pamphlet for public consumption, explaining why Lamson could not have killed his wife in the manner required by the prosecutor’s case.

A prescient colleague gave the Winterses a 19th-century book, Famous Cases of Circumstantial Evidence, including real-life accounts of the failure of justice. Lewis was struck by the 16th-century story of Martin Guerre and his wife, Bertrande de Rols.

Guerre abandoned his family and returned eight years later a changed man – or did he? Was he Martin Guerre at all? The case of imposture wracked southwestern France, just as Palo Alto had been roiled by the Lamson case.

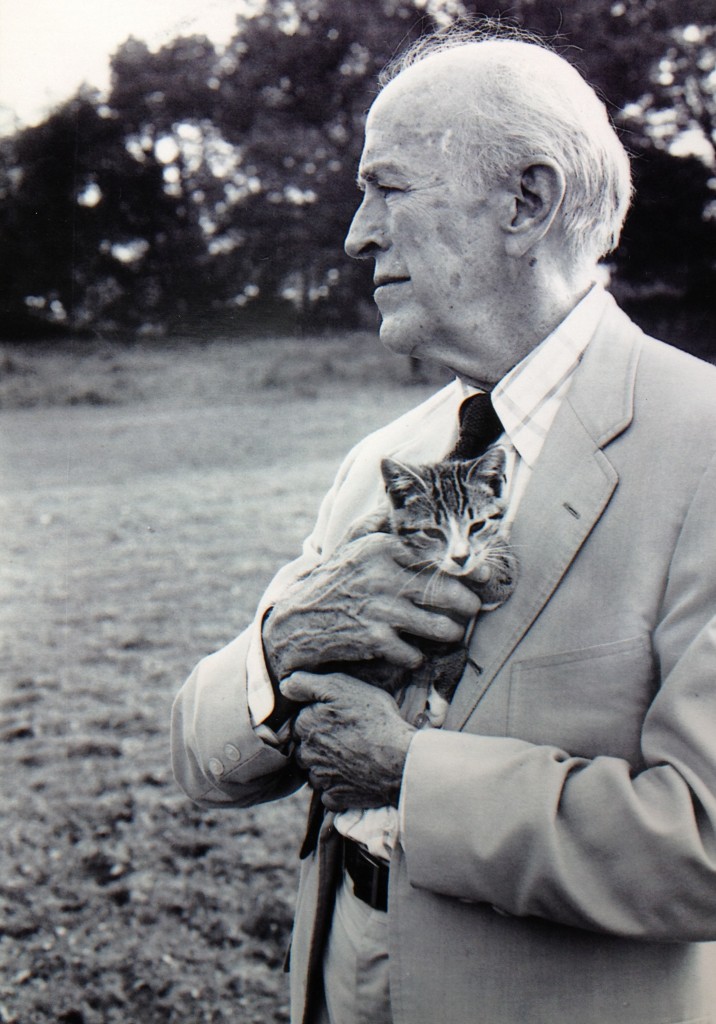

Outraged … and right.

According to the New York Times, “Miss Lewis pursued a literary life in which the focus was on the life and the life was one of such placid equilibrium and domestic bliss that she had to reach deep down in her psyche – and far back in the annals of criminal law – to find the wellspring of tension that produced some of the 20th century’s most vividly imagined and finely wrought literature.”

But for Lewis, The Wife of Martin Guerre was also born of her love for France. Lewis had been a French major at the University of Chicago. According to her friend, poet Helen Pinkerton, Lewis’ passion for the country began in 1920. For her graduation, her father gave her a round-trip ticket to Europe and $400. Lewis got a job with the passport office on Rue de Tilsitt, behind the Arc de Triomphe, and stayed for nine memorable months. She returned with a John Simon Guggenheim fellowship in 1950.

There was another reason for Lewis’s novels and short stories: Lewis was a gifted poet, but her prose brought more money than verse – and the Winters family of four needed the extra cash. In pre-war days, academia was still something of a gentlemen’s profession, with many professors holding independent incomes.

Moreover, colleagues who had been riled by Winters’ pugnacious opinions delayed his promotion to a full professorship until he was 50 years old – although he went on to get an endowed chair, a Bollingen Prize, a National Institute of Arts and Letters award as well as grants from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

David Levin, writing in 1978, recalled that the Lewises “lived in extraordinary simplicity”: “The plain furniture in their small house in Los Altos did not change in all the years of our association, and Winters drove a 1950 Plymouth Suburban from 1949 until he stopped driving in the year before his death,” he wrote.

Her friends describe the Winterses devotion to their Airedale terriers, their cooking and their gardening in the Los Altos house they’d assumed in 1934 and never left.

The poet in her 90s. (Photo: Brigitte Carnochan)

Lewis nevertheless made time for her writing – and perhaps the externally uneventful life contributed to the celebrated psychological poise. The British poet Dick Davis wrotein London’s Independent: “Her books possess a quality of deep repose, a kind of distilled wisdom in the face of human disaster and pain, which is difficult to describe and impossible to imitate, but which, once encountered, is unforgettable.”

Lewis has never been short of admirers: W.H. Auden, Marianne Moore, Theodore Roethke, Louise Bogan and others praised her work. Yet writer Evan Connell observed, “I cannot think of another writer whose stature so far exceeds her public recognition.”

In the years since her death, her reputation has been fostered by a circle of friends, including Los Angeles poet and Stanford alumnus Timothy Steele, who praised her poems for their “clear-sightedness” and “intelligent warmth.”

“They’re full of joy and sorrow. It’s very directly stated. No evasiveness. She doesn’t hide behind ironic postures or anything like that,” he said. “She is someone who has both a sense of the permanent patterns of existence and the transitory beauty of living things, of people and animals and plants.”

Steele recalled, in particular, a party on a summer day at the home of Helen Pinkerton and her then-husband, English Professor Wesley Trimpi. “Among the guests was [political philosopher] Eric Voegelin. He was brilliant, wearing a three-piece suit and discoursing very eloquently about Plato,” remembered Steele. “Janet appeared and said happily, ‘Does anyone want to go for a swim?’

“It seemed such a contrast – a rewarding experience in both cases. She was so vital and connected with physical activity and the warm summer afternoon.”

In any case, Lewis didn’t wait for a reply, but headed for the cabana and changed into her swimsuit for a quick dip. She was well into her 80s.