Take heart from award-winning translator Mira Rosenthal! “A dirty secret I keep is that I started horribly.”

Monday, July 16th, 2018

Tomasz Różycki: The “thematic weight of previous generations” and an “ironic attitude,” too.

I had the pleasure of meeting Mira Rosenthal when she was a Stegner fellow a few years back at Stanford. But I met poet Tomasz Różycki even earlier – at a party hosted by Izabela Barry in Westchester, when An Invisible Rope: Portraits of Czesław Miłosz launched in New York City back in 2011. She had been his translator, bringing him into English, and we chatted about that over coffee in the Stanford Bookstore.

I was pleased to see she’s been interviewed over at the Center for the Art of Translation. An excerpt:

“Sound drives sense, not the other way around.”

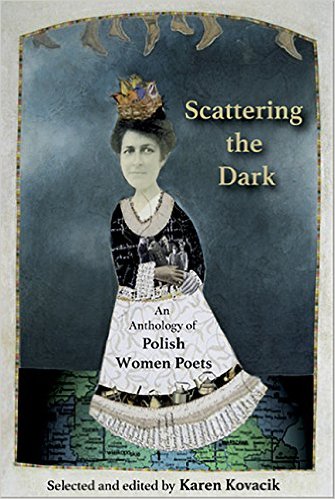

Poland has an amazing poetic tradition, which I first became enamored of in English translation—poet’s like Czesław Miłosz, Anna Swirszczyńska, and Zbigniew Herbert—so much so that I decided to learn the language in order to be able to read their work in the original. When I went looking for more voices, I was both intrigued and disappointed to find that many younger poets had turned away from this post-war generation. In their desire to escape the burdens of recent history, they ended up embracing the New York School of American poets as models instead. How liberating Frank O’Hara’s I-Do-This, I-Do-That poetics must have been after Miłosz’s insistence on pondering the nature of good and evil.

What appeals to me about Różycki’s poetry is that he somehow has found a way to straddle these two stances. He engages with the thematic weight of previous generations while also cultivating an ironic attitude toward contemporary, urban experience, which also means a certain globalized experience today.

EW: How did you start with some of Różycki’s more formal poems, the series of sonnets, for example? Have you found yourself writing in form?

MR: Well, a dirty secret I keep is that I started horribly. And it’s well preserved in print! I began much more loosely than I ended up because, as a beginning translator, I was too concerned with sense. I cut my teeth on Różycki’s poetry—which is partly why it’s so easy now for me to drop into his work, his voice, his outlook, the weight of certain words that he uses repeatedly, and know what to do as a translator. I’m now translating the work of another poet, Krystyna Dąbrowska, and I don’t feel the same automatic facility. There’s an initial getting-to-know-you period in which I have to learn what a particular writer requires of me as a translator.

MR: Well, a dirty secret I keep is that I started horribly. And it’s well preserved in print! I began much more loosely than I ended up because, as a beginning translator, I was too concerned with sense. I cut my teeth on Różycki’s poetry—which is partly why it’s so easy now for me to drop into his work, his voice, his outlook, the weight of certain words that he uses repeatedly, and know what to do as a translator. I’m now translating the work of another poet, Krystyna Dąbrowska, and I don’t feel the same automatic facility. There’s an initial getting-to-know-you period in which I have to learn what a particular writer requires of me as a translator.

At first with Różycki’s poems, I figured that, in order to get the sense right, I would do away with meter and rhyme. Many translators had done so before with similarly formal poetry. But I was never really happy with those versions, even though they were picked up by journals. One of the main distinguishing characteristics of Różycki’s poetry is the sound: it convinces through its lyricism. You know, the kind of poetry where you’re not really sure that you understand what’s being said, but you’re overcome and moved by the language. As a writer, I know well the truth in the idea that sound drives sense, not the other way around.

Read the whole thing here.

Failure is the key human experience, and her words were all the more powerful for being spoken in the Bay Area and Silicon Valley, a place where success is both addiction and the drug itself. We trumpet our successes on Facebook, perpetually shine our C.V.’s, and forge ahead in our determined effort to “brand” ourselves and market ourselves. We risk replacing the face with the mask we have created.

Failure is the key human experience, and her words were all the more powerful for being spoken in the Bay Area and Silicon Valley, a place where success is both addiction and the drug itself. We trumpet our successes on Facebook, perpetually shine our C.V.’s, and forge ahead in our determined effort to “brand” ourselves and market ourselves. We risk replacing the face with the mask we have created. “you shall want for nothing,” let’s say,

“you shall want for nothing,” let’s say,